Integration Or Disintegration, That Is The Question

Leon SacksThe objective here is not to be alarmist or suggest that there is a binary choice between life or death, as in Shakespeare’s allusion. It is, however, meant to draw attention to the need for continuous focus on what keeps a professional services firm, and more particularly a partnership, ticking and successful, namely the integration and collective behavior of its partners.

Integration means that partners are working in the same direction towards a shared goal, that that they are aligned in managing their teams and representing the firm and that their capabilities, knowledge, experience and relationships complement each other.

Disintegration is a danger when there are conflicting priorities amongst the partners and divergent opinions about the way business should be conducted and individualistic rather than collective behavior becomes prevalent. The partners or groups of partners become isolated and unhappy and the firm may become a composite of fiefdoms rather than a homogenous unit.

The current reality of disruption with rapid changes in demand and supply chains is challenging leaders and management in the corporate world. In a partnership such challenges are often magnified by the fact that partners consider themselves co-owners of the business, desire to have a say in how business is conducted and wish to share the benefits.

While overseeing the quality of work, client relations, finances, talent, business development and efficient operations, management needs to be attuned to the concerns, motivation and behavior of partners that, untreated, might be detrimental to the achievement of goals in all those areas. Just as a relationship of a married couple needs to be managed so does a partnership, except that in the latter case the marriage counsellor has to deal with multiple people!

Clearly management deals with partner issues on a daily basis and often this means putting out fires and/or spending a great deal of time in managing people’s expectations or explaining why a certain decision makes sense. Issues will always arise but would it not be more efficient to have integration as a permanent item on the agenda knowing that it will require continuous action as the firm grows and changes and as its partners’ careers advance and ambitions change?

Conditions that might indicate the need for greater integration efforts include:

- partner grievances or departures

- extensive partner discussions on strategy, structure or processes

- incompatibility between partners

- doubts raised by partners about contributions of others

- reduced partner performance or motivation

- unsuccessful lateral integration

- reduced retention rates of attorneys

- individual v institutional behavior

- offices or practice groups working autonomously

- different approaches to service delivery and client management

- little or no sharing of information

- “my clients” attitude prevails rather than “our clients”

- partner compensation system not perceived as fair

- complaints of excessive centralization or lack of flexibility

- inconsistent quality of service perceived by clients

These conditions might not have been a common trait but as a firm grows, the partner ranks grow, the number of offices/practices grow and the firm adapts to market conditions, they may develop quickly. If they are not isolated and become a pattern, management needs to evaluate the causes and adopt a remedial action plan.

As suggested earlier, it is preferable that this be done on an ongoing basis taking the temperature of the organization and the status of the partnership on a regular basis and adjusting accordingly – what we might call the integration “agenda”.

The integration agenda should aim to ensure:

a) Partners are “supporting sponsors”

The alignment of partners with the vision and strategy of the firm and their consistent adherence to common and agreed-upon principles is key to leading the firm in the right direction. They should all be supporting sponsors of the firm’s direction and communicate a consistent message in that regard. Partners are largely the face of the firm to clients and its professionals and their behavior weighs heavily on the way the firm is perceived.

b) Strategy drives structure

Whatever the message for integration, if a firm’s structure drives behaviors that are not aligned to that strategy, it will not succeed. As the Harvard Business Review once stated “leaders can no longer afford to follow the common practice of letting structure drive strategy”.

A crude example: if two offices of a firm are organized as two business units with their own local management and the partners in each office are compensated largely based on the results of their own office, a strategy of sharing resources and cross-selling might be prejudiced or, at a minimum, not incentivized.

c) A collaborative environment

Collaboration generates internal synergies (e.g. sharing talent and knowledge) and external benefits (e.g. client development) while allowing partners to feel more connected to each other, reduce their levels of stress (hopefully!) and enjoy more work freedom. Incentives and support for collaboration that reflects a more institutional approach to conducting business are to be encouraged. This is by no means inconsistent with an entrepreneurial approach to business or rewarding individuals for extraordinary performance.

It is not uncommon to find firms consisting of different groups or individuals that are somewhat autonomous, take different approaches to service delivery and client development and work largely in isolation from others (the “composite of fiefdoms” mentioned earlier). This is rarely a pre-meditated or deliberate action but rather derives from different cultures and work habits (resulting from previous experience in other organizations) and behaviors driven by the firm’s governance and partner compensation system (i.e. what is my decision-making authority and how is my compensation determined).

To be an “integrated” firm, a firm that is effective in providing solutions for clients and is efficient in its use of resources, it is imperative to create a unified culture and adopt governance and compensation models that motivate a one firm approach. Consequently, principles that typically underpin integration may be summarized under three headings:

Governance

- the governance and decision-making structure be clear and understandable

- the management structure reflects diversity of practices and offices, but with all decisions aligned to the firm’s strategy and to the best interests of the firm as a whole

- the governance structure reflects the importance of practice and industry groups as natural integrators across offices and jurisdictions

- authority and policies for decision-making be delegated as appropriate to avoid shackling the organization while allowing for risk mitigation

- Committees and task forces with appropriate partner representation deal with ongoing issues (e.g. Compensation Committee, Talent Management) and specific projects (e.g. Strategy Review, Remote Working), respectively

- a partner communication structure that allows partners to be continually informed and feel they are being consulted on issues of relevance to the business

Partner Compensation

- the compensation system provides clarity on expectations of contributions from partners and aligns compensation with such contributions

- adopt the right mix of compensation criteria to motivate and reward both behavior that drives the firm strategy (revenues, originations) as well as collaborative behavior that encourages teamwork and partner investment in the growth of the pie, rather than a struggle for a larger share (cross-selling, training initiatives)

- couple the collection of objective data with subjective inquiries to adequately measure partner contributions and allow for appropriate discretion in applying compensation criteria to promote fair and equitable results

- consistent partner feedback process

Leadership

- build and support a culture with a shared mission, joint long-term goals and shared risks and rewards

- align structure to strategy, clarify roles and responsibilities and enforce accountability

- promote transparency and open communication and be inclusive

- build trust and confidence facilitating interaction between partners and creating a healthy dose of interdependence amongst them

Firms can easily lose the focus on integration, an intangible asset, while they are busy dealing with the tangible issues of day to day operations, developing business, serving clients and controlling finances. It is better to manage integration than recover from disintegration.

Stealth Discrimination: A model for choosing and managing your leaders

Gerry RiskinIf you find yourself responsible for the leadership of a law firm of a significant size, then you need no convincing to realize that you have far too little time to accomplish even a small portion of your objectives. In many cases, you still carry a client load that most mere mortals would find overwhelming.

At the end of the day, you – like everyone else – will be judged. No one will remember the excuses, only the achievements.

The premise for this article is that since you do not have the resources to attain perfect leadership for every group in your firm, you must decide where your biggest return is – and then discriminate in terms of where you put your efforts. Your only hope is to choose effective leaders who can in turn help the various pieces and parts of your firm succeed in the missions that will have the greatest impact on your future.

While this article was conceived for managing partners, you may be able to transpose the principles to your own situation, regardless of your position.

“Busy” – The Grand Excuse

If you are too busy to manage even your most important group leaders, and they in turn are too busy to manage their constituents, then there are only two rational options open to you. First, you can abandon management altogether and hope that everything will work out well. (Even entrepreneurs don’t take risks like that, but it isn’t far from where many law firms are today.)

The other option is to reduce the scope of what you wish to accomplish. Trying to do too much with an extremely limited amount of time is a traditional trap. We’d prefer to make a case for concentrating your efforts on a few key areas.

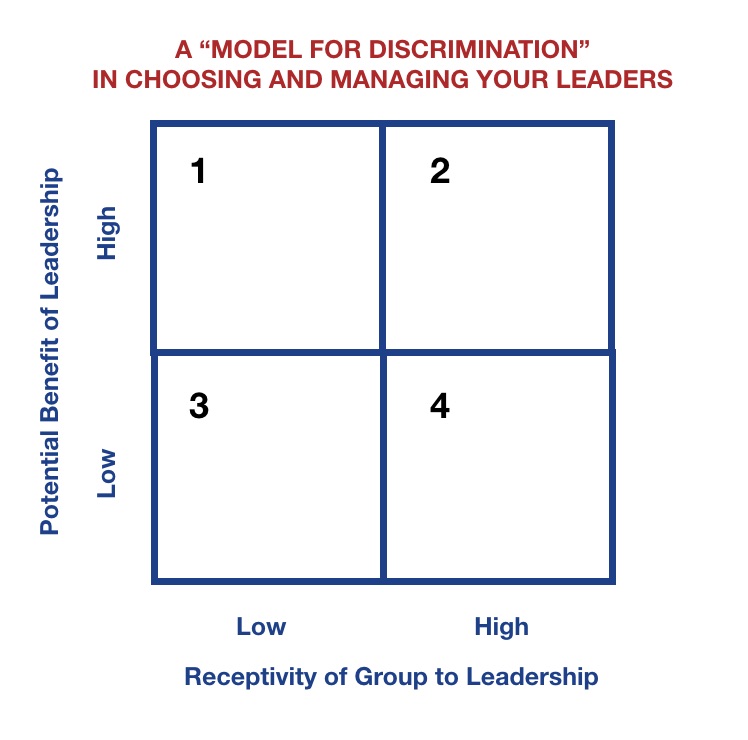

Consider the two factors that would play into such a discriminatory approach.

Factor One: Potential Benefits of Leadership. I would suggest that some groups would benefit from leadership far more than others. For example, a group that has significant potential in making inroads into an emerging area of practice – like intellectual property /biotech, where there’s a potential for incredible value-added service (think genetically altered agricultural components) – would benefit far more from excellent leadership than a group that is dealing with a declining area of practice, like individual residential real-estate deals.

Granted, both groups could benefit from leadership and in a perfect world would have leaders suitable to their situations. The IP/biotech group would benefit from an entrepreneurial leader who can assemble capable people and drive the practice forward with verve, while the residential real estate group might benefit from an administrative leader who is an excellent caretaker and who can develop cost-effective internal systems.

Factor Two: Willingness to Be Led. I further suggest that groups can be distinguished by virtue of their willingness to be led. For example, a young dynamic team that perceives vast opportunity may show considerable hunger for vision and direction, while another group may be, for all practical purposes, a collection of senior sole practitioners who are perfectly happy to remain independent and free, and who would aggressively resist the notion of either vision or direction. You might argue that the second group is not a group at all – nor should it be – but such configurations are not uncommon.

Of course, most groups are not monolithic and have characteristics at many points on the spectrum. We could perhaps call them “hybrids.” However, such ambiguity does not absolve you from deciding on the dominant nature of each group, and then courageously managing it accordingly.

The “Discrimination” Model

Think of each group in your firm as it relates to The Discrimination Model, as illustrated here. Read the attributes below the image, then imagine you are compelled to make a choice and decide into which quadrant each of your groups would fit.

.

Attributes of Constituent Practitioners in the Model

.

- Quadrants 1 and 2 (high potential benefit from leadership): Promising future work and/or practice areas. Highly value work. High hourly rates. Cutting-edge substantive practice areas and/or industries-served. Expertise often requires combined disciplines. Unusual, extraordinary individuals.

- Quadrants 3 and 4 (low potential benefit from leadership): Dying practice areas. Routine work. Large proportion of practitioners nearing retirement. Practitioners practice separately, not as team. Clients are in declining industries.

- Quadrants 1 and 3 (low receptivity to leadership): Maverick practitioners. Little teamwork. Sole practitioner mentality. Perhaps too valuable to remove from firm, but not the core of the firm’s future.

- Quadrants 2 and 4 (high receptivity to leadership): Dynamic individuals seeking a direction. Individuals aware of significant potential. Junior members of team requesting help from more experienced. Requirement to share knowledge among members is high.

Required Attributes of Leaders in Model

.

- Quadrant 1 (high potential benefit from leadership; low receptivity to leadership): Leader requires strong interpersonal skills. Seniority. Prestige in practice area. This leader would benefit from leadership skills training to deal with difficult constituents.

- Quadrant 2 (high potential benefit from leadership; high receptivity to leadership): These leaders are the firm’s most important. These must have skills beyond mere seniority, prestige. These leaders require the ability to enthuse, to envision, and to take on assistant leaders who can attend to detail and continuity. These leaders require most of the firm leader’s attention. It is essential that these leaders have leadership skills training.

- Quadrant 3 (low potential benefit from leadership; low receptivity to leadership): These leaders require the ability to communicate as a liaison between the group and the firm’s management, and to ensure that an adequate level of administration is attended to.

- Quadrant 4 (low potential benefit from leadership; high receptivity to leadership): This leader might, above all else, focus on skill development, knowledge-sharing, and the creation of systems. The group is already receptive to leadership, but the objective here is to maintain adequate systems and to prod additional profitability from those systems rather than necessarily create new ones for the future.

Hybrid Groups – The Grand Challenge

A common reaction to this analysis, and the suggestion that you slot groups according to a discrimination model, is that it might be fine for groups that are almost homogeneous but not applicable to the more common heterogeneous groups. While most groups do have attributes that cross the spectrum of analysis, most will have dominant attributes and those are the ones on which you should consider focusing. My advice here is to forget the labored refinements of lawyering. Trust your visceral instincts. Go with your hunches. You won’t be tested in a court and, if you believe you have made a mistake, you can return and regroup your choices in a number of imaginative ways. In the meantime, force yourself to place the groups somewhere on the matrix.

If you find that a group “just doesn’t fit anywhere,” ask yourself whether such a group really is a group or if it might be a composite of several groups. If so, you may need to render additional breakdowns into component subgroups.

If you accepted the premise that you have far too little time to accomplish the things you need to accomplish, then I hope it follows that you will need to discriminate in the allocation of your time in favor of those groups that fall into Quadrant 2 of The Discrimination Model.

Unless you can be all things to all people, you might as well help those who would benefit from leadership and who genuinely want it. The results for the firm will reinforce your decision. Remember, you won’t be judged on explanations but on results.

Many of the larger firms we advise do not see their managing partners having hands-on involvement with each group and group leader. Instead, they show a configuration where department heads and/or executive committee members each have responsibility for a few groups. At such firms, The Discrimination Model is as important to each intermediary leader as it is to the managing partner.

A structure in which group leaders report (albeit indirectly in many instances) to executive-level partners can be a potent institutional force on the national or global stage, but there’s a fundamentally determinative question that comes first: How effective are the department heads and/or executive committee members at “managing” their leaders? If these managers abdicate their responsibility to manage the leaders for whom they are responsible, then, far from potent, the structure is instead a disabling barrier for the managing partner. That’s because he or she must now face the political cost of overriding the ineffective people layered in the middle.

Capable Leaders – The Grand Prize

Leaders whom you choose for the groups in Quadrant 2 are going to have the biggest impact on your firm’s success and on your reputation as a leader. It may make you a fabled leader. After all, this is the cutting-edge of your firm where maximum receptivity is coupled with maximum potential benefit. These leaders will need to be action-oriented to the point that they will appoint assistant leaders (second-in-command “lieutenants”) as necessary to ensure that they achieve their objectives. Furthermore, their assistant leaders will have attributes that complement theirs. These are the individuals who should be a priority for leadership training.

Can you name a great president with a terrible cabinet? Have you ever heard of a great commander with pathetic generals? Those leaders whom you have considered “great’ have accomplished great deeds through others, or at least with a lot of their help.

The leaders you select will be like you, in the sense that they do not have sufficient time to achieve all of their objectives on their own. They, too, will require the talent to achieve through others. You will therefore need to make absolutely certain that each Quadrant 2 leader has a capable lieutenant. This “lieutenant” may be called something quite different. If the leader is “chair” of the group, the “lieutenant” may be the “administrative head” of the group, or the “co-leader,” or the “assistant leader.”

The nomenclature can be adjusted to fit the politics and realities of the situation. What’s important is actually having such a person, not what they are called. Furthermore, titles need not be consistent throughout the groups of the firm.

The leaders we have seen who are most effective tend to have other leaders assist them who complement their style. For example, hard-nosed leaders who offend fragile temperaments often choose lieutenants who can smooth the waters in their wake. Similarly, detailed-oriented leaders need to ensure that there are visionaries on the team. Perhaps even more important, visionary leaders require detailed-oriented lieutenants who can ensure that the i’s get dotted and the t’s get crossed.

Black Holes and Bright Lights

Some of the leaders whom you appoint will protest. “You don’t understand! I must deal with some idiosyncratic and extreme personalities.” Many groups have within them individuals that might be referred to as “stars.” The relevant question is whether these stars are “black holes” or “bright lights.”

Bright-light stars illuminate those around them. If you think of your favorite sports franchise, you might be able to think of a player who not only has individual star quality but who seems to raise the level of play of the entire team as well. This is a bright light. Conversely, all too many of us can think of a stars who demoralize those around them and operate almost in spite of their team, or group, or firm, rather than in harmony with it. These are black holes.

Black holes, in physics, consume so much energy that even light cannot escape. The gravity is so intense that, at least theoretically, all matter occupies an infinitely small space. The relevance of the black hole or bright light analysis for your stars is to determine how they are to be managed. The bright lights usually do not pose a problem. Unfortunately, this may mean that they are under-managed

in favor of the squeaky-wheel black holes.

The issue with black holes is whether they can be neutralized. Some leaders refer to “black hole” individuals as requiring “high maintenance.”

Can you and the leaders who serve you afford the time, effort, attention that it takes, not to necessarily enhance the performance of the black hole, but rather to simply neutralize the impact so that he or she does not demoralize the team? To their credit, some black holes are easily neutralized. They simply need to be made aware of their influence, and to be asked by someone whom they respect to refrain from behavior that negatively affects the group. The quid pro quo is usually a certain amount of autonomy for the challenging individual.

There are, unfortunately, other kinds of black holes who seem to be unable to either understand or accede to such requests. These black holes are dangerous in that they will consume the efforts of the leader as well as negatively affect the performance of the group. These individuals are tolerated to the detriment of the group and therefore the firm. They should be isolated from the group as necessary or in extreme cases should be allowed to go and live somewhere else, their books of business notwithstanding.

Action Points

I suggest that you might consider the following action steps.

First, assess each current group and place it into The Discrimination Model. First, list each group in the firm. Using a forced choice method – i.e., you must decide! – rate each group on the receptivity/potential benefits axes that comprise the model. Then place the group in the appropriate quadrant.

The only guidance I can offer is that this is a time for “reality,” not “self-deception.” So, do the exercise alone. That will help you to be honest with yourself. This is not a committee decision. Earlier I mentioned that you will be judged for the accomplishments of the firm during your reign. It will be of little help to say, I knew what to do but the committee that advised me democratically forced me on the wrong path.

Second, consider the existing leader of the groups that fall into Quadrant 2. In particular, analyze their competencies and weaknesses against the leadership attributes listed below the model.

Third, manage these leaders by requiring of them that they take on assistant leaders to complement them, both in style and approach, and to alleviate their time burdens. If a Quadrant 2 leader is reluctant to accept such an offer of assistance, remove him or her as leader. You have far too much to lose, and too much to gain, to tolerate an uncooperative leader in the all-important Quadrant 2.

Having said that, you may be dismissing someone with informal influence and importance. If that is the case, it may be appropriate to give such individuals honorary roles; for example, making them chairpersons of the group but not its de facto leaders.

Earlier, I alluded to the tendency among lawyers to want to organize the firm as if drafting an agreement, with perfection and consistency, rather than by trusting your instincts. In this vein, a firm’s leadership should not be configured like a perfectly coherent legal document. As we’ve suggested, different leaders should have different roles, depending on the nature of their group. There should always be flexibility for each group situation.

For example, it should be quite tolerable for a firm to have a chair

of one group but a practice group leader

of another. Rigid conformity to consistency in titles unnecessarily restricts the discretion of the firm leader.

I hope that the analysis contained in this article will allow you to discriminate in a very positive and constructive manner. By determining where the greatest benefit from leadership might be, as well as where the greatest receptivity to such leadership might lie, you can concentrate your efforts on high-yield leadership appointments by knowing which leaders have the best chance to create success in your firm. You can more carefully select them and then more carefully manage them.

Do you abandon the other leaders? No. You just don’t let every proverbially squeaky wheel get your grease. My colleagues and I have often recommended that enlightened firm leaders create a council of leaders who would meet regularly to learn from one another. A small investment of your time on a monthly or, if necessary, bimonthly, basis–meeting with your leaders for a focused two hours, free of administrative distraction – can do a great deal to elevate the management competence in your firm.

By learning to be less demanding of those leaders who are in a caretaker role, in favor of being far more demanding of the leaders of areas that represent the firm’s future prosperity, you will be allocating wisely the most valuable resource of the firm.

That resource happens to be you, and your time and energy as its leader.

Prioritising Initiatives – Avoiding the Seven Deadly Sins

Nick Jarrett-KerrI have often noticed that firms do not always seem to prioritise initiatives sufficiently carefully. My experience is that one or more of the following seven things get in the way of proper planning and implementation:

- He (or she) who shouts loudest for resources will often get them;

- Prioritisation is decided on positions of power or because of internal politics, and not on what is likely to be best for the firm;

- Initiatives – particularly office moves – are agreed on gut instinct in an effort to outshine competitors and with little by way of cost-benefit analysis;

- The managing partner and the top management team end up with a long list of projects, and working partners avoid getting any; lack of resources mean that urgent or easy jobs get done even if they lack importance;

- There is no attempt at prioritisation and the firm ends up with a proliferation of half-completed and abandoned projects;

- Overstretched partners agree to take on projects for which realistically they will have little or no time. Initiatives are agreed upon which everybody knows will never actually happen, usually because of lack of time or proper accountability;

- Projects are decided without proper assessment or analysis, either on a copy-cat basis or on a simple assertion that “we must do this”.

It is of course true that strategic plans generally generate multiple initiatives across the firm, including projects which are both practice-group specific and those which cross group boundaries. But priority decisions need to be made as objectively and clinically as possible. I suggest therefore that strategic initiatives should be tested against four important criteria:

- Strategic alignment – What part of our strategy is this initiative intended to support? What goal or objective is this project aimed at?

- Strategic Benefit and Outcomes – What are the expected outcomes and results?

- Resources – What are the resources needed to bring the project to success? What are the costs and funding implications, and what are the time requirements?

- Capabilities – What is our confidence in our ability to deliver this project? What degree of change is necessary, and what is the risk if things go wrong?

The various strategic initiatives can then be scored or assessed to agree on the most promising set of overall initiatives. This process also helps the firm to arrive at the performance indicators, financial metrics and strategic milestones which should lead to and define success.

5 Pressing Priorities for Professional Providers (This is more than just another PR exercise)

Jordan FurlongIf you like lists and you love alliteration, then you’re probably a legal management consultant. It seems that practically every article these days by people in my line of work features a numbered list of entries that all begin with the same letter. I admit that I often do the same thing in my presentations.

What I propose to do here, however, is even more ambitious. Not only will the following list of five priorities for law firm leaders in 2015 all begin with the letters “pr,” but throughout this entire article, every sentence will contain at least one word that starts with “pr.” Re-read all the previous sentences and you’ll see what I mean.

Presuming that you’re on board with this (gimmick) approach, here are five elements of law firm strategy or infrastructure that will be critical to firms’ ability to hold their own, not just against today’s competitors, but tomorrow’s as well.

- Process. Call it systematization or business improvement or legal project management, the bottom line is that firms must take steps immediately to make their workflow and operations more streamlined and effective. Disciplined procedures for performing legal work enable your firm to both meet budgets and enhance the quality of your work. It also provides a sound basis for…

- Pricing. Client demands for fixed fees or capped budgets or discounted rates all stem from the same desire: to bring more predictability to their legal spend. Your primary focus needs to be on giving clients a reliable range of fees for their tasks. But you can’t just promise a flat fee without knowing exactly how much it will cost you to deliver the work. Pricing your work correctly is a condition precedent for the next important feature on this list…

- Profitability. Too many law firms still measure productivity by hours billed. But a growing minority have finally accepted that the proper metric of financial health is profitability, both firm-wide and matter-specific. When firms adopt this course, prevailing assumptions inevitably give way to provocative truths. The prospect of informing powerful partners that their high-revenue client barely generates a profit can be daunting. But that simply reinforces the practical necessity of developing…

- Protocols. It’s easy to draft mission statements and issue grand pronouncements about your firm’s culture. But when it comes to the crunch, are your leaders prepared to enforce behavioral expectations on your partners? Or even to prescribe step-by-step instructions for how work must be carried out? Peer pressure isn’t enough. Top-down protocols are needed to preserve system integrity, prohibit individual variances, and promote employee morale.

- Proactivity. Any firm can serve its clients’ present needs. But clients are also concerned about their future prospects. How prescient are you about trends in your client’s market or industry? Can you help predict their future opportunities? Or prevent impending disasters? Be proactive about identifying risks for your client before they materialize. Clients truly value lawyers who don’t just solve problems, but who can anticipate and eliminate them.

Prioritize these five features, and you’ll have pretty good odds of profound success in 2015 and many productive years beyond.