Another Look at Practice Group Analysis

Nick Jarrett-KerrMany law firms now have sophisticated methodologies for assessing or measuring the profitability of their practice groups, and yet many stumble across one of three typical issues.

- Many firms do not have a clear definition of their practice and industry groups. The issue is that firms often have too many specialised groups with some overlapping, some small, some historical and even some redundant. Partners and timekeepers can be members of more than one group and their time is sometimes difficult to classify between groups. Even where there is some objective definition of what lawyers and/or work are assigned to each group, revenue-sharing problems can also occur where timekeepers do work on engagements (or create originations) for another group. The least complex (and most popular) response to this issue is to make a clear assignment of all timekeepers to a specific group, but this usually works best in larger firms with highly specialised timekeepers who largely stick within their group. It is also possible to code each time entry for a matter or engagement to an office, practice group or industry group, but this can get very complex quite quickly – its value is only as good as the accuracy of the coding. Some firms also assign specific engagements to a specific practice group and all revenues from the engagement then fall within that group’s profitability analysis. This works fine, but it does require monitoring for the possibility that the engagement may morph into another practice group.

- Overheads – particularly general support costs – are difficult to apportion between groups. When analysis is carried out to a minute level of granularity, I have seen arguments break out about the fairness of allocation of some of the overheads if a group feels it does not make as much use of certain support services as others. The use of marketing and IT are typical examples. Where timekeepers work across more than one group, there is also the issue of how to apportion their cost – the simplest method is often to distribute the cost of each timekeeper proportionately between groups according to the worked, billed and collected revenues by each timekeeper.

- There is no coherent allocation of the cost of partner time. There are three typical views here. The first option is to ignore the cost of partners on the basis that partners are paid out of profits. This carries huge problems in that it understates the operating costs of the group, it works to the disadvantage of highly leveraged groups, and it makes comparisons between groups tricky. Furthermore, it does not easily drill down into individual partner profitability. The second approach is to account for the full cost of partner compensation as part of the overhead. The problem with this approach is that it overstates the operating cost of groups, since it reflects benefits of ownership beyond compensation for work (capital at risk, client origination, and management activities) and results in small marginal differences among groups. In my view, the best option is to calculate a notional “salary” for equity partners. This is usually triangulated between (1) levels of monthly drawings, (2) the highest salaries payable to non-equity partners, (3) market salaries (where evidence is available). Even this method has a disadvantage in that the element of nationality can be seen as removing accuracy from the profitability calculation.

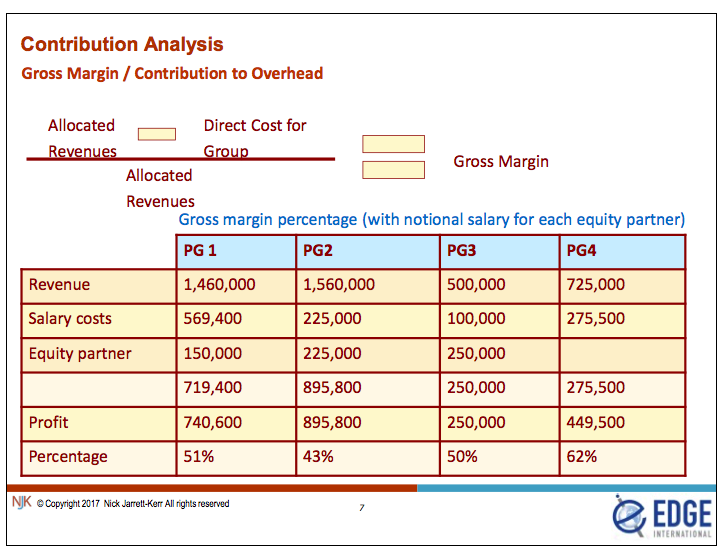

Once the firm has resolved and defined all of the above issues, the attached table shows how a typical Contribution Analysis can provide a simpler answer than a full and detailed Practice Group Profitability Analysis. It has the great benefit of being able to compare the profitability of groups on a fair basis