Navigating the Compensation Maze

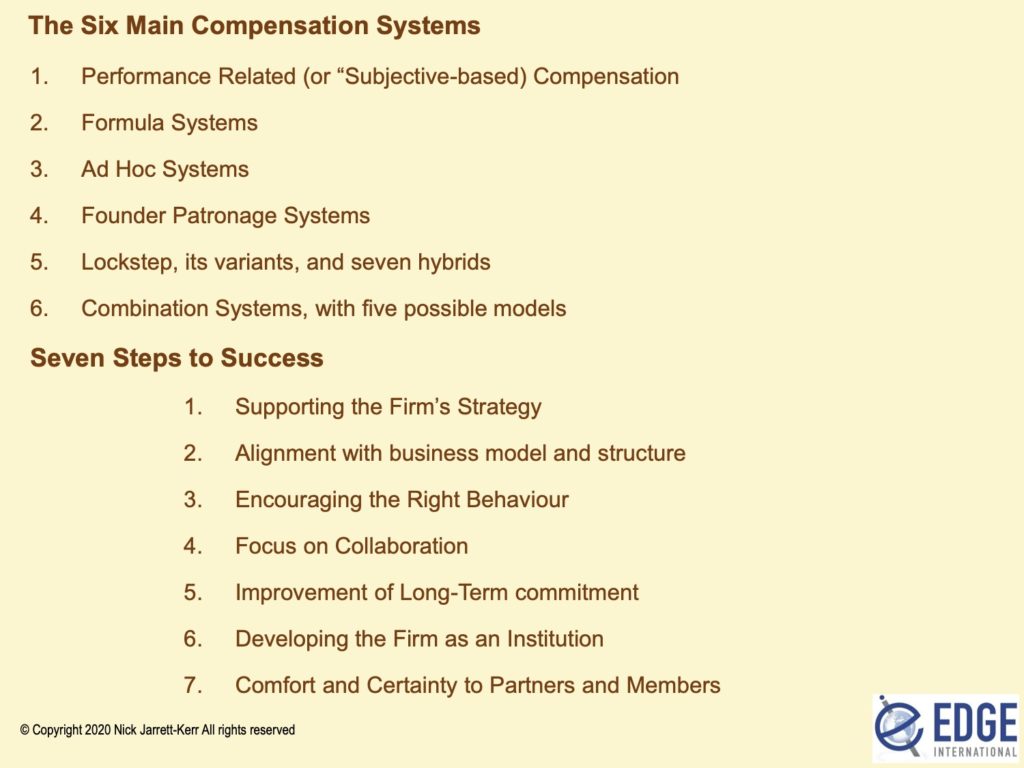

Nick Jarrett-KerrA Guide to the Six Main Systems, Sixteen variations, and Seven steps to Success

Introduction

The last twenty years or so have seen considerable debate about the most suitable method of compensating and rewarding professional service firm partners and members. The traditional practice model of a professional service firm has long been the partnership model, a model that has also for some years developed into a partnership/corporation hybrid in which the partnership model of compensation has remained dominant. Over the last decade or so, more and more professional service firms have morphed into corporate models and this has introduced complexities to the various compensation models in use. In traditional professional service firm models, the individualistic Eat What You Kill (EWYK) model is seen as one extreme of the spectrum, whilst the purer forms of equal-sharing lockstep schemes are viewed as being at the opposite end of the same spectrum. In truth, the use of models at both opposing ends of the spectrum have largely become rare. Many firms have constructed arrangements which try to meld the ethos of true partnership with something that encourages a hard-working in which individuals can be rewarded on a performance related basis

In this paper, I attempt to review the development of the more recent and bewildering trends in partner compensation in relation to the six main historical compensation systems. This includes a review of the adaptation and cannibalisation of the different systems, usually based at least in part on the firm’s history and in part on current profit drivers and imperatives. In a separate paper, I review the main methods of reviewing and assessing partner contribution.

The Six Main Compensation Systems in Professional Service Firms

There is no single system that has suited every professional service firm in the past and – as firms move towards greater degrees of corporate structures – there are likely to be many systems that attempt to incorporate or hybridise the best of the “Big Six” whilst attempting to avoid the drawbacks.

System One: Performance Related (or ‘Subjective-based’) Compensation

There is a discernible global trend away from both pure lockstep and the more individual and statistics-based systems such as Eat-What-You-Kill and Formulaic systems. Approximately 70% of U.S. and Canadian law firms primarily base their partner compensation on subjective criteria.[1] In accountancy 5% of US firms with 8+ partners use a compensation committee to allocate income vs. 15% using formulas[2]. The trend at both ends of the spectrum is towards a more performance-related system relying on qualitative or ’subjective’ assessments. The exact make-up and structure of so called subjective-based systems will vary enormously. Firms moving towards performance related systems will usually keep some vestiges of their historical or formula-based systems and many provide some certainty and security for their partners by fixing base salary or compensation tiers for their partners.

Some large international firms have moved onto compensation and rewards systems which are wholly performance based. Such firms often have as many as nine to twelve bands and partners are allocated into bands on an assessment of the sustained value which they have brought to the firm. In other words, the firm tries to look not just at one year’s performance but for long term contribution. Some such firms will look two years back and one year forward to arrive at a view.

There are many examples of such firms worldwide. Typically, the firm will place partners in one of about eight or nine bands. A former partner of a UK-based international firm recently told us somewhat cynically that the top band is designed to ensure that a very small number of ‘power partners’ get more than $1 million per annum. The bottom band is an entry level band. In most firms with a system like this, the bands themselves are arranged so as to have significant gaps between bands – $100,000 or more is a popular band interval and there are often band intervals of up to $200,000.

Structurally, the firm will – as with performance criteria – tend to fix the highest and lowest bands first. The highest band will represent what the firm feels it must pay (assuming it is affordable) to the firm’s star performer or performers, whilst the lowest band will represent a fair market package for an incoming equity partner. The other bands will be arranged with suitable intervening gaps between top and bottom.

Although this methodology can theoretically lead to huge uncertainty (as partners have no assurance or guarantee of what band they might be in next year), firms will often provide that partners can move up no more than two bands in any one year and have the certainty of knowing that they can only be demoted by one band in any one year. We have also seen some partnership provisions which provide for almost automatic expulsion if a partner is demoted more than once in a reasonable period of time.

The point should be clear by now that movement either wholly or in part onto performance related (or subjective-based) compensation should not be attempted until and unless all the partners are crystal clear as to what the firm expects its partners to do and how it needs them to behave. However small, the firm decides what the performance-related part of the overall compensation should be. Whatever the balance between client work production and other more ‘subjective’ areas, the firm has to decide the areas in which it wants its partners to perform as well as the criteria for success – those behaviours and outcomes which the firm will value and reward. In addition, it has to form a view as to how the ‘subjective’ factors are going to be assessed, scored or judged.

System Two: Formula Systems

A formula system requires the firm to gather information such as billable hours recorded and billed, new business generation (originations), and collections, and then enter the data into an allocation formula which then spews out the compensation distribution. Many partners assume that most large firms – particularly in the USA – operate on such a highly objective, pure formulaic system but by my observation, however, only about 10% of large firms use a strict formula. Roughly one-third of firms have a system that at least in part is subjectively determined or moderated by a compensation committee based on consideration of data, interviews with partners, recommendations by firm leaders and similar inputs. At the other end of the spectrum, I estimate that only about 5% of firms use a pure lockstep system where profits are evenly divided among partners or where seniority is the sole determinant of compensation, but another 10% have a modified lockstep system where the seniority-based rise up the compensation ladder may be affected by performance factors. The remainder (about 40%) is some combination of two or more of these factors, most frequently an objective system that can be modified by subjective input.

Eat What You Kill (EWYK)

Typically, in an EWYK-based system, performance as a practicing professional is objectively measured by a combination of originations and work performed. Although this approach is usually modified to include a few other performance criteria besides only billing, it still means that the professionals in the firm that produce are rewarded commensurately, while those that don’t are penalized. The advantages of this system are that the firm can pay the premium salaries that the very top talent demands, and that the system self-corrects for professionals that want to reduce workload, perhaps for lifestyle reasons. For middle-sized and emerging firms, a highly incentivized system such as this may be the only way to attract top talent.

Under the extreme form of this system each partner bears a share of firm overhead, but pays the salary of his or her secretary or assistant. Also, individual marketing, continuing education, personal technology and memberships costs are the responsibility of the individual partner. The time of juniors is purchased from the firm at set rates but charged out to clients at whatever billing rate the partner thinks is appropriate. Partners can also sell an interest in a particular file to another partner at a negotiated rate. (Typically, the client originating partner will get 10 percent of whatever is billed by the other partner.) Having dealt with all of the costs, the partner then gets to keep 100 percent of all receipts.

The extreme version of the system does have strengths. As every partner has total responsibility for his or her income and clients, partners know exactly what they must do to achieve the income levels they desire. The system provides incentives at various levels. First, the partners will want to bring in business for others because they get a percentage of the billing when they sell the file to another partner or when they get a junior to manage the file. There is also an incentive for hiring and retaining only profitable, hardworking juniors so that they can maximize their own incomes. There is a strong motivation for partners to collect their receivables because it is their own money. Lastly, the firm will maintain tight controls on spending because partners will not tolerate too large an overhead allocation. There is no pie-splitting animosity because there is no pie-splitting. Everything is dealt with at an individual level.

Formula Systems

Under a “pure” formula system an allocation methodology is set up which typically is designed to reward ‘Finders’, ‘Minders’ and ‘Grinders’. Whilst firms might weight each of these three areas, many will simply weight each with 33.3%. This then becomes easy to measure – you simply calculate the volume of work introduced, the volume for which the partner is responsible in terms of being a team manager and the volume which the partner actually generates from his own efforts. The formula then applies to work out each partner’s compensation. There are many problems with such systems. First, we have encountered many formula systems which do not recognise or reward all the criteria necessary for a firm’s success. A formula has to operate against numbers and some factors are intangible. Second, formula systems have been proved to be easy to manipulate. Third, formula systems are highly inflexible.

Agreeing a Formula for Credits (“Originations”)

All surveys in the legal and accountancy sectors confirm the continuing importance of tracking originations. It seems that about 70% of firms who track originations continue to do so indefinitely with about 10% preferring to end originations after a number of years. For origination credits to work fairly, there must be agreement on the rules for the identification of the originator, for shared credits, for changing allocations and for ending (or not ending) the duration of the credit. The basis for the originations formula goes back to the 1940s, when the Boston law firm Hale and Dorr created what is regarded as the first incentive-based compensation system. Under a modified version of this, 10% of profits would go to the finders, 20% to the minders, 60% to the grinders and 10% to a discretionary pool for allocation on a subjective basis. One firm that still uses originations extensively is US law firm Flaster Greenberg. In that firm thirty percent (30%) of the total amount available for distribution is allocated proportionately to the shareholders based on origination, nineteen percent (19%) is allocated proportionately to the shareholders based on minding and fifty-one percent (51%) is allocated to the shareholders proportionately based on production. Shareholders receive the same production credit regardless of whether they work on a client file they originated or another attorney’s file.

The firm argues “The financial credit for origination is divided into two categories – origination and minding, which allows attorneys to share credit for client acquisition and management. Accordingly, attorneys are rewarded for each step in a client relationship – bringing in clients, managing the file and performing the work. This means that minding attorneys are rewarded for servicing and growing the client.

The delicate balance between rewarding originators and rewarding the working attorneys is maintained as evidenced by the fact that both the firm’s high originators and high billers have remained at the firm.

Avoiding the Pitfalls in Formula Systems

In most major firms, the trend is away from compensation which is highly driven by partners individual client-related efforts. The biggest drawback is that such systems are anti-institutional. As such, they can be a good vehicle for smaller firms but are not really suitable for firms as they grow larger. Because no one gets recognition for non-client time, there is often a void when it comes to firm management, training of juniors, firm marketing or human resources. There is certainly no room for those with a global mindset. Additionally, such systems create no need for collegiality other than as a method to market other partners for work for their clients. Often partners don’t even talk to their colleagues unless they have a financial or personal reason to do so. That, in turn, spreads throughout the firm, creating a very difficult environment for most staff, juniors and even some partners to work in.

One further huge drawback with performance-based compensation systems is that they can become expensive nightmares to administer, if the metrics are not carefully selected. On the one hand, people do not as they are told but as they are rewarded, so the system needs to reward exactly the kind of behaviour that the firm desires. If practice leaders are measured on their individual contributions to billing, then they will not delegate, manage, coach or do anything else that fails to drive their individual billing. If securing new work is rewarded, existing clients will tend to be neglected. If originations are rewarded, then people will tend to pay attention to business development. [3]

System Three: Ad Hoc Systems

Although we have no explicit survey evidence to prove it, there are a great many professional service firms throughout the world who have historically allocated their profits and partner compensation on a fairly informal basis and continue to do so. We have however noticed that this exercise becomes more difficult and contentious once the firm grows to about fifteen or so equity partners, members or shareholders. Above twenty or so partners, formal systems and structures generally become necessary.

Many firms employing ad hoc compensation systems started as family or sole proprietor firms where the founder partner or partners set all the rules and provided all of the leadership and partnership control. As partners came in, they were allocated profit-sharing and compensation packages by the controlling partner or coalition of partners, and their shares tended only to increase over time if the firm leaders so decided or where the firm is faced with defections. Firms with strong and controlling leadership, whether or not from a founding partner, have much to commend them. The famous ‘herding of cats’ problems do not apply to firms where partners have to do what they are told. Such firms, however, usually find that both a spirit of entrepreneurship and continuing profitable growth of the firm will eventually become stifled unless heavy central control and dictatorship develops into a more sustainable institutional model. This generally leads to the formalisation of the rules for equity membership, progression and compensation.

Other firms have continued to adopt an annual negotiation where compensation allocations are discussed or fought over by the entire partnership. In some firms, each partner fills out a slip of paper with his or her compensation proposals and these are then aggregated. In some firms, this system is done anonymously; partners will see what other partners have proposed but they do not know who made which recommendation. A variation of this is the open method where partners know who recommended what. This can certainly lead to robust debate! Occasionally, a remuneration or compensation committee is appointed to apply rough justice without any detailed rules of engagement or criteria being agreed.

Ad hoc systems therefore can range from a heavily autocratic extreme to a predominantly democratic model where every partner is allowed an equal say in compensation setting discussions. They can work well or badly depending on the level of trust and the culture of collegiality within the firm. Partners generally need to have the comfort of knowing that their overall contribution to the firm is both known and being fairly taken into account. Systems which are perceived to favour the popular partners and those who are best at selling themselves and their accomplishments within the partnership often act to disconcert those who prefer to keep themselves to themselves, or work in more humdrum areas of practice.

System Four: Founder Patronage Systems

As a variation of ad hoc systems, I have noticed some firms where the influence of the founder partner or group of partners continues to influence the profit-sharing and compensation allocations. Founders often maintain an iron grip on their firms generally and a rigid control on the equity of the firm in particular. The introduction of new equity partners in the typical founder firm often takes place when the need for succession planning is identified, when the firm starts to stagnate (and needs an infusion of new talent) or when the firm’s growth starts to outstrip the ability of the founders to control the growth within a rigid employment hierarchy. When founders recognise the need to introduce new equity partners, their mindset often is that they are ‘giving away’ a share in the firm to their new partners, many of whom have been employed salaried partners for many years and were chosen originally for technical skill rather than leadership qualities. This patronage mindset can continue for a long time after the firm is opened up to new blood and is demonstrated by the founders deciding all compensation issues against inevitable complaints of favouritism and arbitrariness.

System Five: Lockstep and its Variants

Under a Lockstep or seniority-based system, an individual Partner, upon admission to the Partnership, is exchanging individual earning power and intellectual capital, for participation in a ‘mutual fund’ of other Partners. Through this, a Partner is able to share in the joint future incomes of all Partners, some of whom will be contemporaries and some of whom will offer differing levels of expertise and experience gained through the years.

A lockstep system has a number of attributes

- Each Partner’s share of Profits depends entirely upon his seniority

- In any given year, the relationship between Partners at different levels is pre-determined

- The system recognises that Partners take time to find their feet following entry to Partnership

- The system emphasises the mutuality of Partnership, and the sense of sharing and support which should exist between Partners

- Lockstep is essentially a sharing model of Partnership, emphasising the gains and benefits to be had from diversifying opportunities and spreading risk amongst a group of Partners, and away from an individual ‘eat what you kill’ mentality

- The system distinguishes between the personal attributes and earning power of each Partner (his ‘individual human capital’) and what the firm’s institutional capital – that which cannot be easily removed from the Firm, or duplicated outside it and described above

- The system encourages a more collegial environment in which Partners are encouraged to pursue the firm’s best interests, rather than their own

The Perceived Benefits of a Lockstep system

For a firm with a large element of firm-specific intellectual capital, the sharing or lockstep system has some important potential advantages. The main benefit is to provide outstanding diversification and to reinforce a culture in which clients are viewed as firm clients and in which efficient teamwork is encouraged.

In the case of many lockstep firms the client is regarded as central to their whole ethos, and for such a firm a culture of firm before self’ is entirely consistent with a sharing, lockstep model of profit sharing. What is also clear is that the presence and level of firm-specific capital is so marked in such firms that they are potentially much more profitable for individual partners than alternatives outside the Firm. This in turn reduces the risks of poaching by other Firms. This is borne out by the research of Messrs Gilson and Mnookin[4] nearly forty years ago who found that the concept of firm-specific intellectual capital explains why some sharing firms achieve substantial efficiencies, tend to be amongst the most profitable professional service firms, and avoid some of the risks of partners grabbing clients and leaving the firm.

The Draw Backs of Lockstep

Lockstep is seen as having the following disadvantages

- It does not deal explicitly with the issue of underperformers or shirkers

- It does not deal with the issue of exceptional high flyers

- It does not reward, sufficiently quickly, superior young Partners

- It can reward moderate partners to a greater extent than they deserve

- Even if underperformance is not a problem, nevertheless, in the world of professional services there is a fine line between the good partner and the excellent one.

- It can prove difficult to find the right pace on the equity ladder for lateral hires

In the Lockstep firm, the problem of shirkers and underperformers is seen as more of a management and development problem than a problem of reward. Firms with a Lockstep or Sharing system of Profit Sharing tend to be less tolerant of poor or mediocre performance than firms which make extensive use of individual performance based rewards. The attitude can be very much one of ‘shape up or ship out’. The problem is that not every issue of underperformance results from laziness or lack of intellect. The underlying causes for underperformance can include:

- Cultural problems, including complacency, coasting and a desire to remain in a comfort zone

- Partners who have reached the limits of their capabilities

- Partners with personal difficulties or under stress

- Failure to understand why it is necessary for new approaches to be adopted or new tasks to be done

- Mental blocks on how to raise the game

- Conditions in the Market Place

The experience of a number of Firms is that a reduction in profit share to cope with underperformance brought about by some of the causes listed above, can tend to demotivate the Partner still further with the result that performance levels drop still further.

Trends for firms retaining ‘pure’ lockstep

We see many firms across the world that are wedded to the concepts and values of ‘true partnership’ and equal sharing which finds its expression in the lockstep principle. However, many such firms are tending to sand down the edges of pure lockstep in order to maintain flexibility and the ability to manage performance.

As a Partner moves up the lockstep and grows within the partnership, firms generally expect his/her contribution to increase. This does not relate to the overall hours spent on Firm business or the degree of collaboration, but to the value that the Partner brings to the Firm. Firms very often therefore provide benchmarks and criteria which they wish to see partners attain as they develop through the partnership. These benchmarks are supported by training and coaching and monitored via appraisal . At the same time, these benchmarks and criteria will often provide the minimum acceptable standards for partners of the firm, protracted or persistent under-shooting of which will result in the partner being asked to leave. The more caring firms will sweeten this frightening prospect by providing for a period of intensive care and coaching to allow the partner to address his or her perceived shortcomings.

Variations of Lockstep (Hybrid Lockstep)

More radical solutions have also made their way into the structures of many firms. Some 60% of UK law firms now report, for instance, that they have introduced some form of modified lockstep. This is particularly the case where firms do not want to admit new partners if those partners are going to progress automatically to parity. Equally, many firms are reluctant to go the whole way into a pure performance-related system but wish to retain the flexibility to even out elements of unfairness and to make some measure of alignment between individual contribution and individual rewards. Many of these ‘hybrid’ systems seek to give partners two things. First, it gives certainty in that partners will know in advance what their guaranteed minimum income will be assuming the firm meets its financial targets. Second, partners know that they will also be rewarded for performance in due course.

What is important to bear in mind is that the system must support the firm in its growth and in the attainment of its objectives. We have seen many such modifications but they tend to fall into one or more of the following eight types.

Lockstep Hybrid One: Managed Lockstep

A managed lockstep is one where the progression up the lockstep ladder is assumed but not presumed. The firm will preserve the right in exceptional circumstances to hold a Partner at his/her current position on the lockstep, or even to reduce points, if that Partner’s performance does not warrant progression. In addition, there will often be a “gateway” at one or two places on the lockstep through which a Partner can and will pass only if the firm agrees that he/she should progress further. Some firms also retain the right to advance a partner through the lockstep faster than the standard progression and in some cases to reduce a partners share.

Lockstep Hybrid Two: Lockstep plus discretionary performance related element

Another variation provides for Lockstep to apply to the major part of the firm’s profit pool, but the remaining part of a partners profit share is performance related. There are two main methodologies currently in play. The first methodology divides the profit pool into two parts, with one part allocated to the lockstep and the other part reserved for performance related allocations. We have seen some firms allocate as much as 40% of the firm’s profit for distribution on a performance related basis, but commonly the percentage is between 15% and 30%. The advantage of this methodology is that partners can often be persuaded to feel that, unless they are perceived to be underperforming, all partners will receive something from this part of the profit pool.

The second methodology provides for 10, 20 or 30 additional merit points to reward retroactively for superior or exceptional performance, but with a re-base to 100 points each year. Some such systems seek to restrict the effect of such a provision by providing that points for superior or exceptional performance are unlikely to be awarded to more than a fairly small percentage of partners.

Lockstep Hybrid Three: The Super Plateau

The super plateau system is a managed lockstep under which, having reached 100 points (which would be the points plateau for a firm operating with a lockstep to 100 points), an exceptional partner can then progress further to a super plateau which is reserved for a very few star partners. This super plateau generally operated prospectively in that partners are moved on to the super plateau on the assumption that future performance will match or exceed past performance.

Lockstep Hybrid Four: Lockstep plus formula bonus

A further variation gives a partner a formula bonus in addition to his points-based profit share. This bonus generally operates as a first slice of profits and is based on a percentage of the partner’s realised billings. This is not a popular system as it can reinforce tendencies to hog work and to be anti-collaborative.

Lockstep Hybrid Five: Exceptional bonuses for extreme high flyers

Some firms also provide for the ability to award an individual payment in order to reward a “one-off instance” of exceptional performance.

Lockstep Hybrid Six: A two-tier system with a lockstep ‘salary’ element plus discretionary performance-related element

Under this system, a partner will receive a ‘salary’ which will usually have some relation (at least at entry level) to a market salary for a professional of similar seniority and market worth. These ‘salaries’ are banded and partners will move up the bands in a similar way to lockstep progression. The aggregate of the ‘salaries’ payable to partners operates a first tranche of distributable profit, and the residual profit is then allocated on a performance related basis.

Lockstep Hybrid Seven: A three-tier system – salary, ownership shares and performance-related element

A further variation is designed to align partners’ profit shares more closely to remuneration methodologies in the corporate world. Like senior employees of a corporation, a partner will receive a ‘salary’ plus a ‘dividend’ plus a performance related bonus. The ‘salary’ is either reviewed regularly on a market basis or simply banded with partners moving up and down salary bands in a similar way to lockstep progression. Again this salary operates as a first tranche of a firm’s profit. The ‘dividend’ is received by means of the allocation to each partner of owners’ points (sometimes known as Proprietorship Points) on lockstep principles. The residual profit (after deduction of the aggregate ‘salaries’, is then split between the amounts allocated for owners’ points on the one hand and a performance element on the other.

Lockstep Hybrid Eight: Fixed Value Points systems

Firms operating internationally or with major profit differences between offices or regions whilst operating on a common profit pool usually build in some variation in the value of points. The invidious alternative is to vary the actual number of points allocated with the effect that eminent or senior lawyers in different markets will be on different profit shares, which can cause difficulties. In general, the points allocation to each individual should be based on their peer group position on the lockstep, or their performance level relative to others, or a combination of both. However, it is then necessary to recognise and reflect differences in profitability between offices, or purchasing power differences, or both, by adjusting the value of points between the various markets. There is an important psychological issue in this approach in that it has all peer group partners on the same level of points so it is according to them an equal level of seniority or performance or both. This can be quite important in status terms and in motivation. People can feel undervalued if their level of points varies from their peer group: this is much less where the value of a point varies because of external factors.

System Six: Combination Systems

It is very difficult for any firm entirely and radically to change compensation systems to an entirely new model. The vast majority have preferred an incremental approach to change. Hence, modifying a mainly formulaic or algebraic system to a combination system reflects the desire to maintain at least some of the attributes of a system to which partners have become used and in which they have some levels of confidence. The aim of a combination system would be to retain some elements of formula whilst assessing partners for overall contributions. The eventual objective might be to end up with three elements (like banks) of salary (to reflect effort and production), dividend (to reflect ownership state) and bonus (to reflect good contribution). The approach of firms has been multifold but some examples are:

- Formula plus Subjective Assessment. A combination of an algebraic formula based on performance with a subjective element based on a balanced scorecard. One accountancy firm mentioned in Aquila and Rice’s book[5] for instance used a 75% formula approach and 25% for subjectively assessed performance

- Base salary plus formula. All partners receive a base compensation (Salary) fixed at market rate or as a proportion (say 60%) of their average compensation over the past three years and the balance of the firm’s distributable profit (after deduction of the aggregate salaries) based on formula. The latest Rosenberg survey found that 86% of CPA firms have a base salary tier. The base salary, usually 65-75% of total compensation, is both the historical and street value of a partner and gives both established and incoming partners confidence that their basic financial needs will be met

- Formula Salary with the balance assessed on a subjective basis that takes into account overall contribution

- Salary with a proportion of the residual profit being subjectively assessed and a further proportion being carved out into a bonus pool for allocation after year end for exceptional performance in that year

- An alternative approach is for all senior professionals to receive a base salary which reflects their efforts and status as working professionals with the remainder of the distributable profit being allocated through a combination of the existing formula and an adjustment to reflect non-financial contributions

Making Sense of it All; Seven Steps to Success

In our fast-changing world, with a bewildering choice of different compensation systems, it is vital to work through seven critical steps:

Step One: Supporting the firm’s strategy.

By far the most important aspect of a firm’s compensation system and underlying policies is that it must support the firm in achieving its strategic and economic objectives. The system needs to help to underpin a unified understanding of where the firm wants to go, where it is likely to prove to be successful and what trade-offs are likely to take place along the way. Sadly, many compensation systems reward the past, and perhaps the immediate and short-term future; those who are working prospectively towards longer term goals can lose out in the pie sharing contest.

Step Two: Alignment with the firms business model and structure

The firm’s business model is the framework by which the firm competes, generates revenue and delivers profit. For many firms there is an uneasy balance between high volume, low margin work at one extreme and lower volumes of ‘bespoke’ one carried out at high partner rates at the other extreme, and these differences need to be taken into account in assessing the value of partners’ contributions. The firm’s structure – partnership, limited liability partnership, LLC or corporation – is also a vital determinant of compensation alignment

Step Three: Encouraging the right Behaviours.

Third, the system must encourage the behaviours, performances and contributions which will assist the firm in meeting its goals. Whilst this may seem obvious, there is a worrying trend towards encouraging and rewarding short term behaviour at the expense of longer-term investment. This means making sure that the firm clearly defines what it needs from its partners and – if possible – ensuring every partner has a written business plan and specific goals.

Step Four: Focus on Collaborative Effort.

Fourth, it must assist towards the development of a cohesive organisation by focussing on collaborative effort. This makes for a difficult balancing act between the encouragement of individual performance and the drive for better teamwork. The hogging of work to boost personal performance is still an issue in most firms.

Step Five: Improvement of long-term Commitment.

Fifth, the system must improve commitment, engagement and enthusiasm to aim for further and better business success. As I have suggested elsewhere[6], we all spend large proportions of our lives at work and we owe it to ourselves and our firm that our career and the environment in which we work should be stimulating, satisfying and even fun. I would go further and suggest that the pursuit of happiness in our firms is more important than the pursuit of profit.

Step Six: Developing the Firm as an Institution.

Sixth, it must assist the firm in developing as (or into) an enduring institution by concentrating on the development of its intangible assets – those features that make the firm unique and competitive, such as specialist niches, systems, processes and know-how. Included as important aspects of any firm’s institutional capital are its ethos, internal ecology, expected sets of behaviours and ways of doing things – in other words, its unique organisational culture. The compensation system should acknowledge and support the assets and value of the firm as an ongoing institution, taking into account, in particular, the value of the predictable flow of work from an established client base, the ability for partners to work from established premises and with the firm’s systems, equipment and staff, the reputation and name of the firm and the consequent value of the firm as a means of quality assurance to existing and potential clients. Other factors in the firms institutional capital include the efficiencies and economies of scale associated with the firm, its collected know-how and applied knowledge and the synergies obtained from the development of expert teams across a broad range of professional disciplines

Step Seven: Comfort and Certainty to Partners and Members.

Finally, over many years of experience we have consistently found that partners and owners of professional firms need the following for their systems of compensation:

- Transparency, certainty and predictability – the system needs to be easy to understand, the processes easy to follow and any judgements or assessments seen to have been made with scrupulous sincerity

- Security – they need to know they can fulfil at least their basic monthly financial needs

- Good accounting practice – any (such as accountants) with a financial background need to know that the system is credible, logical and not overly complex

- The absence of major change – we have found time and time again that it is difficult to get partners/owners to agree a wholescale transformation of the compensation system; incremental change is preferred

- Fairness – in particular, partners/owners are reluctant to feel they are likely to be subsidising colleagues who they perceive to be slacking or under-performing

- Overall contribution is valuable – most (but not all) want to feel that their overall contribution is taken into account and not just their financial performance

Conclusion

The ultimate choice of profit-sharing system depends very much on the specific firm’s history, culture, jurisdiction, size and maturity. Our own preference is for a system with a meaningful performance-related element of compensation or reward which is based on a qualitative assessment of every partner’s total contribution to the firm across a number of critical areas of performance. However, such a system will not suit every firm. We are seeing many firms still seeking to stick as closely as possible to what they see as the true partnership ethic which equal sharing and lockstep represents. This is particularly true of those firms with large elements of firm-specific intellectual capital, such as the London magic circle firms and leading New York firms. It is also clear that some firms in start-up mode or in a period of entrepreneurially-driven growth will continue to be attracted to the relative simplicity of an Eat-What-What-You-Kill system. There will also continue to be a body of firms which are either heterogeneous motels for professionals or where both the business model and the emphasis are on individualistic business builders and fee barons. For such firms the more formulaic models of compensation will continue to have their place.

What is clear is that every system requires active and robust management to ensure that partners do not creep their way up to progression beyond their competence and contribution.

[1] The Edge International Global Compensation Survey

[2] The Rosenberg Survey 2019

[3] See the Ten Terrible Truths about Law Firm Partner Contribution by Ed Wesemann (August 2006) available from www.edge.ai

[4] Gilson & Mnookin – Sharing among the Human Capitalists: an Economic Inquiry into the Corporate Law Firm and how Partners split Profits (Stanford Law Review January 1985)

[5] Aquila AJ and Rice CL (2007) Compensation as a Strategic Asset

[6] https://jarrett-kerr.com/ten-steps-towards-a-happier-firm/

5 Compensation Issues to Review at Reopening

David CruickshankPartner compensation cuts. Furloughs. Layoffs. High receivables. Clients in crisis. Despite all these dismal legal media headlines, there will be a reopening of the economy. Demand for legal services will return, perhaps more slowly in some sectors.

Meantime, your firm’s compensation cuts and adjustments are the pain still felt and talked about by all your partners and employees. They’re asking: “Will compensation return to normal?” As leaders, you’ll have to answer and consider tweaks to your pre-pandemic system.

To begin with, leaders should consider a self-assessment of how they handled partner and associate compensation issues during the pandemic. Warren Buffet famously said: “It’s only when the tide goes out that you discover who’s been swimming naked.” While self-assessment can be uncomfortable, it can also pinpoint surprising positives as well as criticisms of past actions. We’ve worked with firms who use surveys, interviews with partners and upward reviews to get honest feedback on their leadership or culture*. An assessment from within or with outside support applies equally to your handling of compensation in the Covid-19 crisis. While every firm will discover different strengths and weaknesses, we predict that these 5 issues will surface in most.

1. Transparency and Trust

In our conversations with partners, we frequently hear that transparency about how compensation decisions are made and what factors influence those decisions is a highly valued feature of a compensation system. In making decisions about recent cuts for partners and employees, leaders should have been transparent about who was affected and why. Ideally, leaders will have consulted those affected in advance. In the recent cuts, some of the best practices did not involve “across the board” or “equal treatment”. They affected partners first, and more significantly. Firms protected lower-salaried employees from any cuts.

How does your recent transparency record match what you normally do with annual partner compensation? To the extent that you were as transparent, or more so, your leadership credibility will be intact. If your self-assessment reveals lower appraisals of transparency, trust in leadership will be eroded.

Transparency builds trust. We hear time and again from younger generation partners that compensation decisions should not be made in a “black box” environment. They do not need to know every detail of each decision or even each partner’s compensation. But they want to know the criteria, have some idea of the weighting and have input about their past and future performance. Do you need to tweak transparency to rebuild trust?

2. Overweighting Originations

When the tide is out, we may find that originations from high performing partners are down, and that average performers had even weaker originations. If firms place high weight on originations, especially over only the past year, the quantitative compensation rankings may be very scrambled at 2020 year-end. There may be pressure to penalize or exit partners at the bottom of the rankings. Those same partners may have proven their worth in more qualitative measures but get little credit. The tweaks to consider will be:

- down-weighting originations, even in more flexible, non-formula systems;

- placing a specific weight on originations and other quantitative factors; and

- averaging originations over two years back, plus the current year.

3. Increased Weighting for Qualitative Factors

We often help firms articulate and measure qualitative performance that will be given weight in partner compensation systems. We think that, this year, some of these factors were very critical to the future of the firm, though we won’t recognize that importance until late this year. Looking at partner performance over 2020, review the partners who excelled at:

- Client relations. Keeping stressed clients informed and supported. Cross-referring those clients to other firm services, such as real estate partners who could help re-negotiate a lease.

- Mentoring, training and counseling. Even the best associates will be concerned about getting enough hours or getting feedback. In a remote working environment, effective partners replicated the office “drop-in” or coffee break discussion by making individual video calls or doing small-group check-ins.

- Innovation. What did partners do to pivot the firm’s business, attract clients to new services or create legal project management innovations? A crisis can be an opportunity for innovators. Does the compensation system recognize innovation efforts, even though some may fail?

If these factors do help offset weak originations and keep associates busy and onboard, should they not be upweighted in the future?

4. Your Benefits Package

When associates and staff reflect on their pandemic experience, the benefits of some meals and the gym membership may not seem as important as some other benefits. First among these, though not listed in the benefits package, is job security. Every associate and staff member will be thinking about this as we move toward reopening. Firm leaders and partners will have to take specific actions, mostly through communications, to “keep the keepers”. Reassure your best people. Talk them through their next level of development.

Health care, sick leave and disability benefits will be under a new spotlight. Firms may need tweaks or new plans to meet new employee and partner needs. For example, will some need leave to care for sick or disabled parents? Do you have such a benefit?

5. The Level of Monthly Draws

In most firms a core amount of partner compensation is really paid in advance of collected profits. These are monthly draws that are viewed by many partners as “guaranteed minimums” (but of course, they are contingent on actual collected profits). On reflection, do you need to re-balance the amount that is pledged to monthly draws compared to year-end distributions? Another common category is a bonus pool amount that is held for year-end, both for associates and partners. That category will certainly be downsized at year end. All the pieces of compensation distribution may need review, and if you are making those adjustments for 2021, the internal consultations have to start now.

We all hope the tide will come back shortly after reopening. A candid review of your crisis response and tweaks to your compensation will demonstrate leadership and stability. Above all, you won’t be swimming naked in 2021.

________________________

*In addition to compensation reviews, Edge performs Cultural Assessments in law firms, to test the reality of the culture the firm believes it has. Contact [email protected] to learn more.

Edge International Global Survey of Partner Compensation

Nick Jarrett-KerrEvery few years, Edge International carries out a short global survey of partner compensation in law firms. It was very much the brainchild of our late and much-missed colleague Ed Wesemann, assisted by Nick Jarrett-Kerr.

Over the last twelve years it has been interesting to track the trends across the world as firms have steadily adopted a more nuanced approach in most jurisdictions than purely formulaic systems or fixed lockstep.

We are planning to run the survey again in late 2018, so please watch out for it. Meanwhile links to the 2012 and 2015 surveys are as follows:

- The Edge International 2012 Global Partner Compensation System Survey

- The Edge International 2015 Global Partner Compensation System Survey

Partner Performance and Compensation

David CruickshankThree years ago in Communiqué, I wrote a two-part article on “Collaboration and Compensation.” Part I appeared in the September 2014 issue, and Part II in the October 2014 issue. Since that time, I have received several inquiries in compensation engagements about partner performance. The inquiries go beyond financial performance and general “team building” activities. Leaders want to know how to reward – explicitly – the activities of partners who contribute to a lasting, profitable firm.

The interest in measuring partner performance more broadly may arise from two developments in U.S. law firms over the past ten years. First, we know that many firms, from global to mid-sized, now use competency models to evaluate and promote associates. These competency systems are a product of influential professional development staffs. They have persuaded leadership to look more thoroughly at who deserves the next tier of those expensive associate salaries. For associates, a competency measure is a specific, measurable skill, knowledge level, analytical prowess or business-development activity. Typically, associates progress through three or four stages of competency before making partner.

Convinced that this works better than lockstep annual promotion for associates, these same firms are asking us if we can’t also measure partner competency (but rename it “partner performance”).

A second influence comes from the recognition that getting and keeping top clients requires a high level of service, value billing and legal project management. A single relationship partner can no longer meet the expectations of big clients. It takes a team. Perhaps that’s why in April, global firm Linklaters announced that it was dropping individual partner metrics for compensation in favor of team-based and client-oriented metrics. Many competitor firms, especially those with dominant origination credit metrics, must be worried that Linklaters is right.

Compensation schemes that recognize a broad spectrum of partner performance do exist, but they have been slow to penetrate the AmLaw 100. Just as competency models were built on what we needed to see in associate development, partner performance models will grow from what we need in modern partners. And that means more than individual financial performance.

These are typical categories that we have developed for creating a partner-performance compensation scheme. I have provided a sample performance metric for each:

- Financial Performance: Partner managed above-average (associate and other) billable hours compared to practice group.

- Business Development: Partner participated in x formal client pitches and shared in a successful outcome in y of those pitches. (In compensation parlance, we term these performance measures [x] and outcome measures [y]).

- Leading People and Groups: Partner was the lead for running legal project management training in his practice group. The result was improved management and billing for three key litigation clients and reduction of write-offs. Net revenue per billable hour also improved.

- Client Relations: Partner led a client team that produced 20% greater revenue (year-to-year) from that client. Her specific leadership activities were: etc., etc. Client satisfaction, as measured in a year-end interview, improved over prior year.

- Firm Building: Pursuant to firm policy, partner transitioned client work valued at $3.2 million to other partners or teams. This was the highest value transitioned in the firm last year.

What do you notice about each of the partner performances above? First, they all involve data that has to be tracked all year, and is often compared year over year. Second, they are all specific; there are no sweeping generalizations such as “active at business development” or “well liked by clients.” Third, financial success and profitability are baked into performance measures that also have a team feature. While it is not always possible to connect a financial outcome, we find that credible measures must at least aim in the direction of firm building and financial success for all.

Is a partner-performance compensation system in your future? Given the expectations of clients and the increasing number of junior partners who were promoted in competency models, we think the answer could be “Yes.”

The “Cheap Grace” of Compensation Systems

Mike WhiteI’m always impressed with how much time many of my clients spend wrestling with their compensation systems. The animating seduction of compensation typically doesn’t bring with it a law-firm appetite for changing what is already in place, but it does tend to make up a lot of firm mindshare.

When you think about it, though, that makes total sense. Compensation is an (and, perhaps, the) expression of managerial imperative and control – “Let’s just put together a bundle of rewards, incentives, and ‘punishments’ and people will do what they need to do . . . ” However, it often falls short of fulfilling its command-and-control potential, as firms can point to partner behaviors that run counter to the incentive structure in place. “The compensation committee and leadership have told the partners that certain ‘good citizen’ factors relating to teaming and collaboration are prominent objective features of the compensation system, yet we’re not seeing a lot of business-development collaboration among the partners . . . ”

Why is this? How can firms rely on managerial tools outside of the compensation system itself to give the system more efficacy?

I have one client that relies on a set of four (what they view to be) objective criteria for determining partner comp: originations, billable hours, receivables/collections, and collaborativeness/existing client growth. The four criteria are well explained and explicit, and the partners know what they mean. Despite this level of clarity, the partners are distrustful of the system and the application of its criteria. One problem is that the weightings of the four criteria are not clear. Also, the system itself is closed. Partners tend not to trust that their contribution relative to any one of the four criteria will result in a certain minimum income level. Moreover, because the system is closed, the partners assume that other (typically more senior) partners are getting the benefit of compensation that should be credited to them. Despite the objective nature and definition of the criteria, partners don’t trust the subjective, non-formulaic, and non-transparent application of the criteria to them. Consequently, many of the “good citizen” collaborative behaviors of which the firm would like to see more are in short supply.

Compensation systems – no matter how well-conceived and documented – can be a form of “cheap grace.” Firm leadership too easily concludes that the compensation-system objectives will be self-executing. Adoption, compliance, and motivation are presumed by the mere fact of documenting the compensation system elements; little effort is put into reinforcing the intention of the compensation through day-to-day communication and modeling. We find that more needs to be done in the typical firm to make the compensation-system inducements a more effective driver of performance. Below are some suggestions that firm leadership and firm “middle” management might take into account when trying to move partner behaviors and performance in an important direction:

- Compensation is as much a snapshot of reality as it is a framework of behavior and performance-inducing incentives. It is at best an imperfect reflection of historical contribution and an imperfect driver of performance.

- Firm leadership gains as much permission to lead as there is trust among the partners in the compensation system itself – trust that it means what it says, trust in how it’s applied personally and individually, and trust in how it’s applied to others.

- Objective compensation criteria applied by a subjective “wrapper” (no weighting percentages, etc.) tend to lose their objective quality.

- Make the criteria formulaic enough so that partners can know what their compensation floor is going to be if they hit certain objectives relative to some but not necessarily all of the criteria. For example, $1.5M in originations should translate into a certain minimum amount of comp, irrespective of performance against other criteria.

- Manage and message – the Comp Committee comes down off the mountain once a year, but the day-to-day operational voices of the firm exist at the practice group level, geographic and office head level, and at other levels representing “the lieutenants” of firm management. These firm lieutenants need to communicate consistently, accurately, and often about what collaborative behaviors the firm is trying to encourage and reward. This is particularly important for less formulaic and more subjective compensation structures.

- Model – management and leadership need to present an imbalanced model of the “good behavior” the compensation system is supposed to reward. If the system encourages partners to involve others in their own under-penetrated, high-potential client relationships, then the senior partners should be the best, most conspicuous examples of such.

- Firm management should provide practice and geographic leaders with clear direction as to what it means to lead on these issues. For example, the tired old monthly practice group meetings should consume less time talking about existing work and more time talking about incented behaviors like collaborative selling, or remarkable forms of outreach, or elective credit sharing.

In short, the work of firm leadership and firm lieutenants really begins once the compensation system is nailed down and documented. Live it! Breathe it! Model it!