Integration Or Disintegration, That Is The Question

Leon SacksThe objective here is not to be alarmist or suggest that there is a binary choice between life or death, as in Shakespeare’s allusion. It is, however, meant to draw attention to the need for continuous focus on what keeps a professional services firm, and more particularly a partnership, ticking and successful, namely the integration and collective behavior of its partners.

Integration means that partners are working in the same direction towards a shared goal, that that they are aligned in managing their teams and representing the firm and that their capabilities, knowledge, experience and relationships complement each other.

Disintegration is a danger when there are conflicting priorities amongst the partners and divergent opinions about the way business should be conducted and individualistic rather than collective behavior becomes prevalent. The partners or groups of partners become isolated and unhappy and the firm may become a composite of fiefdoms rather than a homogenous unit.

The current reality of disruption with rapid changes in demand and supply chains is challenging leaders and management in the corporate world. In a partnership such challenges are often magnified by the fact that partners consider themselves co-owners of the business, desire to have a say in how business is conducted and wish to share the benefits.

While overseeing the quality of work, client relations, finances, talent, business development and efficient operations, management needs to be attuned to the concerns, motivation and behavior of partners that, untreated, might be detrimental to the achievement of goals in all those areas. Just as a relationship of a married couple needs to be managed so does a partnership, except that in the latter case the marriage counsellor has to deal with multiple people!

Clearly management deals with partner issues on a daily basis and often this means putting out fires and/or spending a great deal of time in managing people’s expectations or explaining why a certain decision makes sense. Issues will always arise but would it not be more efficient to have integration as a permanent item on the agenda knowing that it will require continuous action as the firm grows and changes and as its partners’ careers advance and ambitions change?

Conditions that might indicate the need for greater integration efforts include:

- partner grievances or departures

- extensive partner discussions on strategy, structure or processes

- incompatibility between partners

- doubts raised by partners about contributions of others

- reduced partner performance or motivation

- unsuccessful lateral integration

- reduced retention rates of attorneys

- individual v institutional behavior

- offices or practice groups working autonomously

- different approaches to service delivery and client management

- little or no sharing of information

- “my clients” attitude prevails rather than “our clients”

- partner compensation system not perceived as fair

- complaints of excessive centralization or lack of flexibility

- inconsistent quality of service perceived by clients

These conditions might not have been a common trait but as a firm grows, the partner ranks grow, the number of offices/practices grow and the firm adapts to market conditions, they may develop quickly. If they are not isolated and become a pattern, management needs to evaluate the causes and adopt a remedial action plan.

As suggested earlier, it is preferable that this be done on an ongoing basis taking the temperature of the organization and the status of the partnership on a regular basis and adjusting accordingly – what we might call the integration “agenda”.

The integration agenda should aim to ensure:

a) Partners are “supporting sponsors”

The alignment of partners with the vision and strategy of the firm and their consistent adherence to common and agreed-upon principles is key to leading the firm in the right direction. They should all be supporting sponsors of the firm’s direction and communicate a consistent message in that regard. Partners are largely the face of the firm to clients and its professionals and their behavior weighs heavily on the way the firm is perceived.

b) Strategy drives structure

Whatever the message for integration, if a firm’s structure drives behaviors that are not aligned to that strategy, it will not succeed. As the Harvard Business Review once stated “leaders can no longer afford to follow the common practice of letting structure drive strategy”.

A crude example: if two offices of a firm are organized as two business units with their own local management and the partners in each office are compensated largely based on the results of their own office, a strategy of sharing resources and cross-selling might be prejudiced or, at a minimum, not incentivized.

c) A collaborative environment

Collaboration generates internal synergies (e.g. sharing talent and knowledge) and external benefits (e.g. client development) while allowing partners to feel more connected to each other, reduce their levels of stress (hopefully!) and enjoy more work freedom. Incentives and support for collaboration that reflects a more institutional approach to conducting business are to be encouraged. This is by no means inconsistent with an entrepreneurial approach to business or rewarding individuals for extraordinary performance.

It is not uncommon to find firms consisting of different groups or individuals that are somewhat autonomous, take different approaches to service delivery and client development and work largely in isolation from others (the “composite of fiefdoms” mentioned earlier). This is rarely a pre-meditated or deliberate action but rather derives from different cultures and work habits (resulting from previous experience in other organizations) and behaviors driven by the firm’s governance and partner compensation system (i.e. what is my decision-making authority and how is my compensation determined).

To be an “integrated” firm, a firm that is effective in providing solutions for clients and is efficient in its use of resources, it is imperative to create a unified culture and adopt governance and compensation models that motivate a one firm approach. Consequently, principles that typically underpin integration may be summarized under three headings:

Governance

- the governance and decision-making structure be clear and understandable

- the management structure reflects diversity of practices and offices, but with all decisions aligned to the firm’s strategy and to the best interests of the firm as a whole

- the governance structure reflects the importance of practice and industry groups as natural integrators across offices and jurisdictions

- authority and policies for decision-making be delegated as appropriate to avoid shackling the organization while allowing for risk mitigation

- Committees and task forces with appropriate partner representation deal with ongoing issues (e.g. Compensation Committee, Talent Management) and specific projects (e.g. Strategy Review, Remote Working), respectively

- a partner communication structure that allows partners to be continually informed and feel they are being consulted on issues of relevance to the business

Partner Compensation

- the compensation system provides clarity on expectations of contributions from partners and aligns compensation with such contributions

- adopt the right mix of compensation criteria to motivate and reward both behavior that drives the firm strategy (revenues, originations) as well as collaborative behavior that encourages teamwork and partner investment in the growth of the pie, rather than a struggle for a larger share (cross-selling, training initiatives)

- couple the collection of objective data with subjective inquiries to adequately measure partner contributions and allow for appropriate discretion in applying compensation criteria to promote fair and equitable results

- consistent partner feedback process

Leadership

- build and support a culture with a shared mission, joint long-term goals and shared risks and rewards

- align structure to strategy, clarify roles and responsibilities and enforce accountability

- promote transparency and open communication and be inclusive

- build trust and confidence facilitating interaction between partners and creating a healthy dose of interdependence amongst them

Firms can easily lose the focus on integration, an intangible asset, while they are busy dealing with the tangible issues of day to day operations, developing business, serving clients and controlling finances. It is better to manage integration than recover from disintegration.

Partner Teams – the benefits, the challenges and why some partners don’t like them! (Part Two)

Sean LarkanIn Part One of this article I set out, in bullet-point form for the purposes of brevity, what I saw as the:

- Benefits of teams and why partners like them;

In this Part Two I look at:

- The disadvantages of not having them;

- Potential challenges and disadvantages of a team structure;

- Why some partners, in our experience, do not like them!

Remember that in Part One I said that by partner teams we mean a partner with tiers of lawyers by seniority or experience who report to her or him and for whom such partner is principally responsible.

PART TWO:

PARTNER TEAMS

- The disadvantages of not having them;

LAWYERS & FEE EARNERS:

- There is a clear responsibility for lawyers within a team. There is nowhere to hide, from partners or peers, within a team;

- Capability to ‘run a team’ becomes a pre-requisite before a senior associate is considered for or elevated to partner status – this should be a sine qua non!

- Senior lawyers, like senior associates, learn leadership and management on the job – a great preparation for partnership, some would say, the only true preparation;

- Training & coaching takes place where it should, on the job, within the team & organically;

- It is the best way of getting the best out of people & ensuring that no-one ‘falls through the cracks’. A team becomes a supportive, challenging learning environment for lawyers but ideally, a trusting and respectful one. There is always someone to ask questions of or provide support or advice;

- A partner team contributes to ensure a genuine interest is taken in individual lawyers and support staff within the team. This is a foundational element of the Responsible Partner system we have developed and implemented in many jurisdictions. It also builds lawyer engagement (will a person ‘say’, ‘stay’ and go the extra mile);

- This structure facilitates teaching and developing specialist industry sector or practice area skills within the team. We have often seen new practice areas or industry sector specialties spring from this interaction and evolution;

- If something e.g. financial practices, should be done in a particular way, new team members very quickly come up to speed and learn from others in the team ‘how things work’;

- Work products and volumes are properly managed within the team; workloads, types of work and necessary training can be done ‘on the job’, in-house, within the team; and

- The only way to ensure every staff member, legal or otherwise, has a fair chance to reach their full potential. These are expensive resources in time and dollars; it is as well to do all you can to get a good return on the investment.

FINANCIAL:

- Budgets can be set on a team basis (the partner will have an excellent grasp of capability and potential within a team) and attainment is managed by the partner concerned;

- Financial management within the team creates consistency, ensures compliance and application, and the teaching/learning of relevant skills;

- The financial outcomes argument is unassailable, particularly where partners employ qualitative gearing or leverage within their team with high calibre, committed team players who work on quality assignments for good quality clients. Firms who have these tiered partner teams reap substantial financial rewards; and

- There is plenty of empirical evidence industry-wide to support this.

GENERAL:

- Employment Brand and engagement levels, critical success factors, are supported by teams. A firm’s employment brand is what others think and feel of the firm as an employer. This is directly impacted by all the factors mentioned above and in Part One of this article; and

- A well led team operates as a well-oiled team and is more powerful than the sum of the individual parts.

PARTNER TEAMS

POTENTIAL CHALLENGES AND DISADVANTAGES:

- There is potential for work to be held within the team (partners ‘clutching it to their chests’) thereby creating a silo effect;

- There is also potential for lawyers in other areas of the practice to not be used by the team, or lawyers within the team not being exposed to other partners, areas of practice or specialties;

- A team structure creates pressure on the team partner to find work and manage work and the financials within the team;

- Sometimes partners, particularly in larger firms, have been inclined to “over lawyer” (but this is not limited to firms that have a team structure); and

- Note that the issues outlined in the first four bullet points, above, are easily managed by having the partner team system in place as part of the fabric of the firm and having it monitored by leadership and management through various systems that have can be put in place to support it. We have evolved a Responsible Partner system and philosophy, Development Discussion system to support it and Contribution Criteria for partners to ensure they undertake their roles appropriately.

PARTNER TEAMS

DISADVANTAGES OF NOT HAVING TEAMS:

- Unless the firm, work type, type of market and individual partners are uniquely qualified, firms will never reach their potential financial outcomes;

- Most of the advantages outlined above are not possible to achieve;

- Partners get away with making much lesser contributions to the firm and partnership than is required in most successful law firms today;

- Too often, partners with specialties do not train successors in that area of work, do not introduce their clients to team lawyers in an organised, structured way and when they retire the ‘cupboard is often bare’ i.e. no real succession has been provided for in regard to skills transfer, personnel or key clients;

- Legal staff are left in a melting pot of uncertainty as to workflow, quality of work, coaching, feedback and whether an interest will be taken in them or their work and progression in the firm. This results in lowered self-esteem, potential is not realised and lower productivity and sometimes departure results; and

- Firms with an ostensibly good brand, good clients, good workflow, good infrastructure, good lawyers and good leadership/management remain mystified why they are not making more money or doing better.

PARTNER TEAMS

WHY DO SOME PARTNERS NOT LIKE TEAMS?

- A team structure makes it clear where responsibility and accountability lie, amongst other things, for what happens within the team and in regard to the quality of work, workflow and financial and overall performance of individual lawyers. Partners won’t admit this, but this often lies at the heart of objections to team structures;

- Team partners have to coach and train;

- Partners sometimes argue they want to be able to hand their work out around the office in a random manner based on the ‘best person for the job’ (the team structure still provides for this);

- Partners quickly realise they will be measured for how well they run and grow their team;

- Unfortunately, the reality is that many partners do not like this spotlight beamed on them.

PARTNER TEAMS

CASE STUDIES

- A leading senior tax partner and in due course Chairman of the firm, charging at the highest rates in NZ, was practising with no gearing, that is, no team. Following establishment of a team structure, which he enthusiastically embraced, he was over five years able to build a team including two fellow partners and half a dozen lawyers one of whom developed a leading GST specialty, another a highly successful Customs and Excise specialty;

- A senior high-profile matrimonial partner in his mid-60s doing celebrity divorces and settlements practised with no team. Even at that stage of his career he took on the challenge of developing a team and through that built succession and client comfort in dealing with lawyers at different levels of seniority. He achieved these goals within about five years; and

- A chairman of his firm in Australia and leading church law and charities practitioner ten years ago had no succession plan and shared one lawyer with another partner. He retired this year (2020) as chairman and partner leaving a successful partner leading the team together with a third partner as well as special Counsel appointed this year and a group of seven lawyers/fee owners supporting them, all fully trained in his practice and well-known to his clients.

NOTE: in each of the above illustrative examples, the partner-team structure was supported by the Responsible Partner and Development Discussion philosophies and programs.

Planning for Recovery

Nick Jarrett-KerrOriginally designed for the Law Society of England and Wales, but relevant to all law firms globally, Edge International Principal Nick Jarrett-Kerr has created a series of four webinars on the topic of Planning for Recovery. Each webinar lasts about twenty minutes and is available free of charge.

Episode One – First Steps to Recovery (Video 1/4)

Crisis Management and Financial Resilience

- The need for a crisis management team

- Leading from the front

- Business Continuity Planning

Essential Planning Points

- Creating a common purpose

- Analysis of market and resources

- Adapting structure and decision-making

Restoring Equilibrium

- Communicating to reduce stress

- Work on physical environment

- Flexibility for more remote working and technology

Episode Two – Interfacing with Clients (Video 2/4)

Client Contact in an era of social distancing – the positives and negatives

- Building, Developing and Renewing Trust and Confidence

- Building the four qualities – legal work, service, accomplishment and relationships

- Leveraging the opportunities for cost effectiveness and good LPM

- More communications to learn clients’ affairs

- Persistence, energy and oxygen

Communicating with Empathy

- Understanding what keeps the client awake at night

- Getting to stand in your clients shoes

- Avoiding the traps

Episode Three – Spotting Potent Opportunities (Video 3/4)

Reviewing practice areas for opportunities and threats

- Research and analysis

- The demand curve of emerging, growing, maturing and saturating work

- Capabilities

Redeploying Staff

- Skills conversion

- Finding ways of holding on to staff

- redundancies

Building an Action Plan

- Recovering/growing revenue and profit

- Tactics, tasks, metrics and accountabilities

- Objectives and revised budgets

Episode Four – Business Planning in a Changed World (Video 4/4)

Reviewing operations and resources for flexibility, resilience and a fresh start

- Operational Reviews

- Culture of Resilience

- Reviewing Governance for better decision-making

Developing bold but well thought out Strategies

- Making steps permanent

- Zero Budgeting

- Radical Restructuring

Ten essentials for a business plan in critical times

What Does It Take to Be a Thought Leader?

Bithika AnandWe often come across the term ‘thought leader.’ Many of us wonder what is implied by this term, and how one might embark upon the journey of being recognized as one. Contrary to popular belief, those at the pinnacle of their professional journeys or those who are visionaries do not automatically become thought leaders. It is only when they are recognized by others in their particular fields for their expertise, authenticity of information, novelty of ideas and authority of opinions that they can be called ‘thought leaders’. Such individuals require passion for building a network of influencers, consistency in the steering of knowledge initiatives, and the ability to take a stance on issues pertaining to areas of specialization.

In this article, we discuss the role of thought leaders, and what it takes to be on the path of thought leadership.

Who is a ‘Thought Leader’?

A thought leader is an individual who is recognized as having authority in a specific field or area of practice, whose skill and expertise is renowned and sought. This person has proven authority in a specialized area, and is highly regarded by those who wish to excel in that area. Thought leaders are known for being pioneers or for being revolutionary in their thinking, with the ability to intellectually influence the lives of those who are a part of the ecosystem surrounding the area of their expertise.

Choose your Area of Expertise

Just as no great task is accomplished without a plan and a clear vision, becoming a thought leader in a legal field requires clarity of thought. Thought leaders choose an area of expertise and stick to it, rather than attempting to gain experience and disseminate knowledge in every practice area or industry sector. Those who wish to be recognized in future as thought leaders in the field of intellectual property rights (IPR), for example, do not normally need to delve into developments in other fields (say, taxation or insolvency). However, if there are taxation nuances that may affect transactional work in intellectual property, they need to be well-versed in those areas.

Thought leaders may also be more specific in the area of their expertise than others — choosing, for example, niche fields within the IPR practice (trademarks, copyrights or patents, for instance). Whatever the choice, thought leaders must focus on augmenting knowledge in the area they’ve chosen and deepen their skills. Instead of widening the base of their practice across several areas, they will need to dive deeply in a chosen area and understand the allied or complementary areas. When they have direct experience and expertise in a particular area, their chances of being looked up to and followed are robust.

Being the ‘Go-To’ Person Is the First Step

As mentioned above, thought leadership requires consistent demonstration of expertise, exposure and experience in a practice area or an industry sector. An impressive body of work, comprised of years of successful cases, matters, transactions, opinions and legal work are necessary, but these are not enough. Internally, would-be thought leaders need to become the ‘go-to’ person within their organization; externally, they need to become ‘trusted advisors’ to clients, academia, judiciary, peers, competitors and students.

And yet this is only the first step. Thought leadership is more than execution, service-delivery and rainmaking. Thought leadership occurs when you develop and share informative content curated or drawn from your expertise and experience – influencing the relevant industry sector, and not just a few specific clients. Thought leaders involve themselves in initiatives that impact the fraternity as a whole and build credibility through deliberate involvement in issues of larger interest, not all of which are driven by commercial interests. Over a period of time, their opinions and insights are almost considered ‘sacred’ owing to the weight and gravitas they carry. In short, the transition from a go-to person or a trusted advisor to becoming an ‘influencer’ is the first stage in the journey toward thought leadership.

Knowledge Dissemination and Engagement

You’re a thought leader when people start following you, and this ‘following’ is not just subscribing to or following your social media pages. This ‘following’ means that like-minded professionals start aligning with you owing to path-breaking legal work, and your ability to get involved with the business sector in decision-making. Other initiatives include disseminating knowledge through erudite articles, thought papers and participation in government initiatives and policy-making. It is relatively easy in the age of social media to demonstrate one’s expertise through blogs, social-media profiles and online publications. However, effort needs to be made to combine an understanding of the law with economic trends and evolving jurisprudence.

Thought leadership also includes engaging with stakeholders from an area at a more strategic level, enabling the perception-builders to believe in your expertise even when you do not deal with them professionally. Thought leaders make an attempt to share views on the latest economic, legal and social developments. They utilize a network of followers and collaborators to connect with those who are involved in creating federal regulations, and they are invited to make submissions representing their suggestions and viewpoints towards legislative developments. They can also strike a chord with their followers by simplifying statutes and legal jargon, and extending help on a pro-bono basis. Actively engaging with others in the legal sector by way of initiating discussions, answering questions, providing guidance and exchanging valuable information goes a long way toward establishing intellectual prowess as a thought leader.

Beyond ‘Networking’

Thought leadership requires one to go beyond “networking” – i.e., establishing relationships for reasons other than mutual commercial benefit. It involves building relationships in advance of when you may actually need them. There is no scorecard of mutual give-and-take, but an earnest effort to trust the synergy amongst the network of one’s contacts. This facilitates information-exchange and the sharing of ideas among those with a common interest in an area of practice. It also allows individuals to be in touch with contacts and other thought leaders, which enables an exchange of valuable information not necessarily available outside of the network.

Knowledge Insights

Through engagement and dialogue with legal professionals and industry leaders, thought leaders consciously keep themselves updated with what’s happening in the economy, their area of practice and the industry sector(s) they serve, which allows them to learn about legal, sectoral and economic developments. However, while participating in events and discussion forums with other thought leaders is one of the ways to hear and be a part of the voice of the fraternity, voracious reading and investing time in research are also imperative, irrespective of the stage in one’s professional journey. Insights based on credible research and gathered from a network of reliable sources from the fraternity lend trustworthiness to the content of thought leaders, giving them authoritative voices.

Thought leaders align themselves with forums specific to their practice area or industry sector and participate in relevant initiatives, from events to publications. This gives them an upper hand, as all those connected with an industry sector seek access to information before they get to the decision-making stage, especially when such decision-making pertains to high-stakes matters or big-ticket business decisions. At this stage, people reach out to thought leaders for authenticity of information and authority of opinions, rather than seeking only service delivery.

Summing Up

Thought leadership is a tool of differentiation from others in one’s field. Starting from providing a legal perspective on business issues, thought leaders transcend towards engaging with the broader legal community. They influence not just their clients, but also those who form a part of the fraternity, including in-house counsels and legal-team members, C-suite executives, service providers to the legal fraternity, members of the judiciary and academia including students, teachers, etc.

Thought leaders enter into strategic relationships with other influencers and also draw from their experience, audience, peers and followers. Along with sharing substantial amounts of value-added content, they need to get themselves involved in issues pertaining to their areas of practice and industry sectors, which may involve taking a stance that supports or condemns a view.

Most importantly, learning is a continuous process for thought leaders. They are always required to be on top of their game, keeping up with the latest trends and exploring new ideas.

The Death of Deference

Nick Jarrett-KerrLawyers have always been a distrustful bunch, but in the last twenty years the growth of larger law firms on the back of increased accountability and performance management seems to have repressed independence of thought amongst professionals, who have been encouraged to focus much of their effort on fee generation and to leave leadership decisions to the leadership team.

Things are, however, changing. Getting the important decisions made is becoming more arduous, and when the firm leaders think they have pushed a decision through in a professional-service firm, they are increasingly finding that decision being thwarted or ignored by the partners afterwards.

In an environment where speed and flexibility are critical, there are of course an increasing number of decisions that can no longer be channelled laboriously through partners’ meetings. Clearly every-day and week-to-week decisions, such as staffing levels, pricing and infrastructure resources, have to be made swiftly and efficiently. And it is universally accepted that all firms need strong and robust leadership, with a minimum level of consultation and discussion and a maximum level of drive and authority. But in some areas, particularly those requiring long-term change, leaders are also acutely aware of the need to gain wide-spread agreement to their strategies and plans – the need for ‘buy-in,’ to use that overworked phrase.

I am also perceiving somewhat of a sea-change within our western cultures generally – less deference to authority, less respect for tradition, less blind acceptance of leadership. As an example, in my country – the United Kingdom – parliamentarians are flexing their muscles and refusing to vote just on party lines, and many institutions are seeing a rise in ‘people power.’ In the arena of professional services, we have witnessed a huge rise in independent lawyers working as freelancers in virtual and dispersed firms in order to regain their autonomy. In traditional firms, we see an even greater level of scrutiny by partners of the leadership team’s performance, and less tolerance of bullying tactics, amateur superficiality or badly-thought-through proposals

The brutal truth is that there are some decisions where achieving a favourable partnership vote is becoming more and more tricky, and usually not enough on its own to ensure implementation – especially in situations where partners feel the leadership team appears to be trying to enforce blind compliance with the decisions they are promoting. Take decisions that need partners to change behaviours, for example. Partners are unlikely to make large alterations in working practices or in how they do things unless they have been part of the decision-making process.

The trick, for any leader, is to be able to judge between three types of decision. First, there are the sorts of decisions which can successfully be made by the management team without consultation. Second are the proposals which need some level of consultation, but which can be pushed through or negotiated with minimum discussion. Third come the more difficult areas of long-term change which need wide-spread support and ‘buy-in’ to stand a chance of success.

Those in the third category present occasions when the leadership team needs to work hard on ensuring participation and involvement of the partners in the decision-making process. Simply telling the partners what to do is not enough.

Recognising this, many firms have developed a communications approach that at least has the partners feeling that they have been consulted, or that attempts have been made to achieve some level of consensus. But in essence, the scenario often merely changes from a ‘telling’ style to a ‘selling’ one, with the management team employing every trick in the book to railroad and cajole partnership agreement through persuasion and negotiation. It is perhaps no surprise that many partners feel at best guarded and distrustful about the whole process. The sorts of complaints I hear from partners are along these lines:

- “I feel disenfranchised. I don’t know what’s going on.”

- “What’s the point in saying anything? The management team never listens.”

- “It makes no difference to me what’s decided. I’ll probably just ignore it all anyway.”

- “The managing partner has lobbied to ensure he has enough support – so opposition is pointless.”

- “I figured everyone else was in favour, so I kept my mouth shut.”

- “I just wanted to keep my head down.”

- “Frankly, I didn’t have time to read the papers. I had no idea what we were agreeing went so far.”

Accordingly, to achieve success the modern professional firm needs a greater degree of flexibility, professionalism and inter-dependence with the firm’s partners. I believe a better approach for tricky and important decisions is to try to facilitate some genuine views and feedback so that the partners actually do become involved in the decision-making process and are not merely negotiated into acceptance of pre-ordained solutions. But even where attempts are made to achieve this, success is not easily won. What typically occurs is that the leadership team arranges a partners’ retreat or conference, or a departmental away-day, at which the team will attempt to lead an open discussion and ultimately to feel their way to an agreement. Plans and papers are produced, analysed and discussed, break-out groups established, and action points developed. Sometimes, the partnership will end up agreeing with the management team’s checklist and plans. At other times, little seems to be achieved except a lot of hot air.

But however open and genuine the intent, the consultation process will almost invariably suffer from a fatal flaw if internally led or facilitated. The problem is that it is almost impossible to facilitate a genuinely open discussion if you have already made up your mind that your carefully thought out plans and proposals are the right or only way forward. Even if the proposals are accepted, a feeling of resentment can often be evident if the partnership feels it has been manipulated in some way, or that the result of the discussion is a foregone conclusion. What is worse is that superficial external agreement by the partners can in fact mean deep-rooted internal rejection. In other words, it can be dangerous to take silence as consent. In some cases, I have even seen genuinely well-thought-out and sensible proposals voted down by the partners just to show the management team that it cannot always have its own way.

I am not for a moment trying to suggest that the management team should abrogate its leadership and management role in favour of some limp and long-winded form of group decision-making process. But what I am putting forward is that it is often good to get some level of feedback and constructive suggestions from a consultation process before a decision is ultimately made – particularly where long-term change is involved. A genuine facilitation process can achieve powerful results here, so long as the leadership team can avoid being seen as thumping its own particular drum and is prepared to listen and influence rather than control and direct. And it generally can only achieve all that if the process is facilitated by someone other than the leadership team itself. Whilst it is, of course, sometimes possible for these purposes to find an internal facilitator, with the necessary facilitation skills and experience and with no axe to grind, I am finding that it is also an area where the use of an external consultant can add enormous value.

Managing and Growing a Law Firm, Part 3

Yarman J. VachhaIn this final article in the series of three, I highlight the legal scene in Asia, the changes to the legal industry, and the different resources available to law firms for expansion. I also take a look to the future, and share key leadership qualities.

In my first article, I shared my thoughts about managing and growing a law firm and in the second article, I discussed the global legal industry and its challenges.

I have previously discussed why firms need to look to the future, as they cannot live in the past and will soon become irrelevant in this fast-paced, tech-savvy environment. Disruptors are already well established and eating away the market share of many firms. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is here to stay and will become more and more sophisticated. For example, standard contracts are now easily available from the internet and there are other solutions in the market to make the “bread and butter” legal services no longer the “black art”, which at one time nobody understood. And then there is the growth of the “in-house” legal departments eroding business lines.

Leadership for the Future

To future-proof themselves, law firm managing partners need to “lead” and not “manage”. I have encountered many managing partners who manage (and at times micro-manage) rather than lead. Some are good at managing but many miss the critical role of a managing partner, which is to lead, have a vision and to inspire and drive the partners to achieve that vision. Then there are those who are poor managers, the ones that micro-manage or those who are indecisive and are too involved with the detail to see the bigger picture, or simply do not have time to manage. All these recognisable conditions lead to inefficiencies and mismanagement, creating potential financial, retention and reputational risks for the business.

As I shared in the first article, I believe that the day-to-day management of a law firm should be left to business professionals who have the necessary skills and experience. Hiring people with this skill set at an appropriate level for the firm is key. Firms need to hire business professionals at the right level and not under-hire. I would caution that hiring at an inappropriate level (too junior or too senior) will lead to additional issues and may be a wasted investment.

In the commercial world, all well-led and well-managed corporates will have a chief financial officer, chief information officer, chief marketing officer, etc. These are professionals in their own rights, and contribute to the success of the business. Why then do law firms think that partners can run such functions in which they have no real expertise or experience? Part of this stems from a “cost” rather than an “investment” mentality. I think what is not appreciated is that partners are being taken away from their core competencies and thrust into something that they are not trained for. What is not accounted for in the Profit & Loss Account is these lost partner hours that could be better utilised in marketing and discharging work which ultimately adds to the bottom line.

In addition to having a sound professional support infrastructure, it is important for leaders of law firms to interact within the industry, attend relevant conferences, keep up-to-date with major changes in the market, and respond promptly to the changes that are taking place in the industry. Keeping up with the legal press is also a must.

Law firm leaders need to have a strategy and a “laser-like focus” on what they want to achieve, and have a formalised succession plan to ensure there is an ongoing legacy for future generations.

Staying Relevant

The key to relevancy is a vision, a stated purpose, an evolving strategy to move with the times, a laser-like focus on the ultimate goal, investment in a sound and professional support infrastructure. Bringing all these together requires a strong and decisive leader with an innovative and flexible mindset.

Being Inclusive

To achieve these goals, it is very important for the management of the firm to be inclusive and to seek the opinions and insights of the lawyers and the business professionals who can help shape the present and future of the firm. Having a sharing and open culture is also important, so that all employees know what the firm’s vision is, and what they are striving to achieve.

At the end of the day, the management of a firm is in a stewardship role. The priority of these stewards should be to lead the firm and make it better than it was when they were put in the leadership position. Having this mindset will help shape and create a legacy for future generations. I would also encourage management not to take a short-term view on all matters. In particular, longer-term investment strategies are required in this competitive environment, as the firms that take a short-term view are unlikely to survive.

Modern Lawyers

We live in a new age of millennials who are entrepreneurs at heart and are very much plugged into the ‘gig economy’, Much like all of us in this new age, they want instant gratification. This group of young lawyers comprise the engine room of the 21st century law firm, and very much the future of the business. This is where I believe a disconnect occurs. The current leaders and managers in law firms are most likely middle-aged and “Gen X,” brought up in a different age and with different values which included working hard, being in the office 9 am to 9 pm, and coming up through the ranks with the ultimate goal of being a partner in a firm.

This is not necessarily the mindset of the modern lawyer, who has many more life and work choices than the previous generations. Law-firm management has to listen carefully to younger lawyers and take heed of their needs to make them productive and engaged, and to retain them in the business long-term. Opportunities to work flexibly and remotely are high on their list. This could mean flexible working parameters and strong and secure IT systems to ensure effective and productive remote working. If this is what it takes to make this generation more productive and create an attractive long-term career path for them, then firms need to respond appropriately to this changing world with both action and rewards.

Women of Law

Firms also need to address the ongoing issue of women leaving the profession. Law firms lose many talented women in which much investment has been made when they decide to have a family. Sadly, this talent is often lost for good. Firms should do a much better job of providing flexibility and alternative career paths, thus giving these women an opportunity to look after their families while also adding value to the business.

Concluding Thoughts

Let’s not forget that 20 years down the line, the millennials group will be leaders of the firm, and they will have a different set of issues to deal with which we can’t even begin to imagine. I think if the current leaders can forge a blueprint for flexibility, succession, and legacy, this will be ingrained in the DNA of the young lawyers and will bode well for future generations.

In conclusion, my three top tips:

- Have a clear vision and purpose, set accountable milestones for these to be achieved, and be inclusive of all in the firm

- Managing partners need to “lead” not “manage”. Leave the management and the execution of strategies to the business professionals

- Build a firm for the future with innovation, the millennials, and women in mind.

Stealth Discrimination: A model for choosing and managing your leaders

Gerry RiskinIf you find yourself responsible for the leadership of a law firm of a significant size, then you need no convincing to realize that you have far too little time to accomplish even a small portion of your objectives. In many cases, you still carry a client load that most mere mortals would find overwhelming.

At the end of the day, you – like everyone else – will be judged. No one will remember the excuses, only the achievements.

The premise for this article is that since you do not have the resources to attain perfect leadership for every group in your firm, you must decide where your biggest return is – and then discriminate in terms of where you put your efforts. Your only hope is to choose effective leaders who can in turn help the various pieces and parts of your firm succeed in the missions that will have the greatest impact on your future.

While this article was conceived for managing partners, you may be able to transpose the principles to your own situation, regardless of your position.

“Busy” – The Grand Excuse

If you are too busy to manage even your most important group leaders, and they in turn are too busy to manage their constituents, then there are only two rational options open to you. First, you can abandon management altogether and hope that everything will work out well. (Even entrepreneurs don’t take risks like that, but it isn’t far from where many law firms are today.)

The other option is to reduce the scope of what you wish to accomplish. Trying to do too much with an extremely limited amount of time is a traditional trap. We’d prefer to make a case for concentrating your efforts on a few key areas.

Consider the two factors that would play into such a discriminatory approach.

Factor One: Potential Benefits of Leadership. I would suggest that some groups would benefit from leadership far more than others. For example, a group that has significant potential in making inroads into an emerging area of practice – like intellectual property /biotech, where there’s a potential for incredible value-added service (think genetically altered agricultural components) – would benefit far more from excellent leadership than a group that is dealing with a declining area of practice, like individual residential real-estate deals.

Granted, both groups could benefit from leadership and in a perfect world would have leaders suitable to their situations. The IP/biotech group would benefit from an entrepreneurial leader who can assemble capable people and drive the practice forward with verve, while the residential real estate group might benefit from an administrative leader who is an excellent caretaker and who can develop cost-effective internal systems.

Factor Two: Willingness to Be Led. I further suggest that groups can be distinguished by virtue of their willingness to be led. For example, a young dynamic team that perceives vast opportunity may show considerable hunger for vision and direction, while another group may be, for all practical purposes, a collection of senior sole practitioners who are perfectly happy to remain independent and free, and who would aggressively resist the notion of either vision or direction. You might argue that the second group is not a group at all – nor should it be – but such configurations are not uncommon.

Of course, most groups are not monolithic and have characteristics at many points on the spectrum. We could perhaps call them “hybrids.” However, such ambiguity does not absolve you from deciding on the dominant nature of each group, and then courageously managing it accordingly.

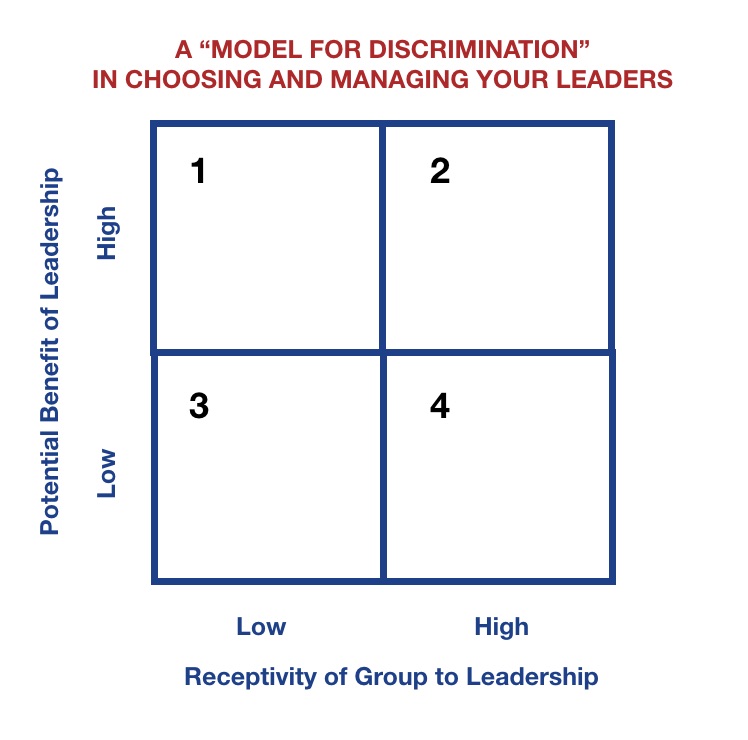

The “Discrimination” Model

Think of each group in your firm as it relates to The Discrimination Model, as illustrated here. Read the attributes below the image, then imagine you are compelled to make a choice and decide into which quadrant each of your groups would fit.

.

Attributes of Constituent Practitioners in the Model

.

- Quadrants 1 and 2 (high potential benefit from leadership): Promising future work and/or practice areas. Highly value work. High hourly rates. Cutting-edge substantive practice areas and/or industries-served. Expertise often requires combined disciplines. Unusual, extraordinary individuals.

- Quadrants 3 and 4 (low potential benefit from leadership): Dying practice areas. Routine work. Large proportion of practitioners nearing retirement. Practitioners practice separately, not as team. Clients are in declining industries.

- Quadrants 1 and 3 (low receptivity to leadership): Maverick practitioners. Little teamwork. Sole practitioner mentality. Perhaps too valuable to remove from firm, but not the core of the firm’s future.

- Quadrants 2 and 4 (high receptivity to leadership): Dynamic individuals seeking a direction. Individuals aware of significant potential. Junior members of team requesting help from more experienced. Requirement to share knowledge among members is high.

Required Attributes of Leaders in Model

.

- Quadrant 1 (high potential benefit from leadership; low receptivity to leadership): Leader requires strong interpersonal skills. Seniority. Prestige in practice area. This leader would benefit from leadership skills training to deal with difficult constituents.

- Quadrant 2 (high potential benefit from leadership; high receptivity to leadership): These leaders are the firm’s most important. These must have skills beyond mere seniority, prestige. These leaders require the ability to enthuse, to envision, and to take on assistant leaders who can attend to detail and continuity. These leaders require most of the firm leader’s attention. It is essential that these leaders have leadership skills training.

- Quadrant 3 (low potential benefit from leadership; low receptivity to leadership): These leaders require the ability to communicate as a liaison between the group and the firm’s management, and to ensure that an adequate level of administration is attended to.

- Quadrant 4 (low potential benefit from leadership; high receptivity to leadership): This leader might, above all else, focus on skill development, knowledge-sharing, and the creation of systems. The group is already receptive to leadership, but the objective here is to maintain adequate systems and to prod additional profitability from those systems rather than necessarily create new ones for the future.

Hybrid Groups – The Grand Challenge

A common reaction to this analysis, and the suggestion that you slot groups according to a discrimination model, is that it might be fine for groups that are almost homogeneous but not applicable to the more common heterogeneous groups. While most groups do have attributes that cross the spectrum of analysis, most will have dominant attributes and those are the ones on which you should consider focusing. My advice here is to forget the labored refinements of lawyering. Trust your visceral instincts. Go with your hunches. You won’t be tested in a court and, if you believe you have made a mistake, you can return and regroup your choices in a number of imaginative ways. In the meantime, force yourself to place the groups somewhere on the matrix.

If you find that a group “just doesn’t fit anywhere,” ask yourself whether such a group really is a group or if it might be a composite of several groups. If so, you may need to render additional breakdowns into component subgroups.

If you accepted the premise that you have far too little time to accomplish the things you need to accomplish, then I hope it follows that you will need to discriminate in the allocation of your time in favor of those groups that fall into Quadrant 2 of The Discrimination Model.

Unless you can be all things to all people, you might as well help those who would benefit from leadership and who genuinely want it. The results for the firm will reinforce your decision. Remember, you won’t be judged on explanations but on results.

Many of the larger firms we advise do not see their managing partners having hands-on involvement with each group and group leader. Instead, they show a configuration where department heads and/or executive committee members each have responsibility for a few groups. At such firms, The Discrimination Model is as important to each intermediary leader as it is to the managing partner.

A structure in which group leaders report (albeit indirectly in many instances) to executive-level partners can be a potent institutional force on the national or global stage, but there’s a fundamentally determinative question that comes first: How effective are the department heads and/or executive committee members at “managing” their leaders? If these managers abdicate their responsibility to manage the leaders for whom they are responsible, then, far from potent, the structure is instead a disabling barrier for the managing partner. That’s because he or she must now face the political cost of overriding the ineffective people layered in the middle.

Capable Leaders – The Grand Prize

Leaders whom you choose for the groups in Quadrant 2 are going to have the biggest impact on your firm’s success and on your reputation as a leader. It may make you a fabled leader. After all, this is the cutting-edge of your firm where maximum receptivity is coupled with maximum potential benefit. These leaders will need to be action-oriented to the point that they will appoint assistant leaders (second-in-command “lieutenants”) as necessary to ensure that they achieve their objectives. Furthermore, their assistant leaders will have attributes that complement theirs. These are the individuals who should be a priority for leadership training.

Can you name a great president with a terrible cabinet? Have you ever heard of a great commander with pathetic generals? Those leaders whom you have considered “great’ have accomplished great deeds through others, or at least with a lot of their help.

The leaders you select will be like you, in the sense that they do not have sufficient time to achieve all of their objectives on their own. They, too, will require the talent to achieve through others. You will therefore need to make absolutely certain that each Quadrant 2 leader has a capable lieutenant. This “lieutenant” may be called something quite different. If the leader is “chair” of the group, the “lieutenant” may be the “administrative head” of the group, or the “co-leader,” or the “assistant leader.”

The nomenclature can be adjusted to fit the politics and realities of the situation. What’s important is actually having such a person, not what they are called. Furthermore, titles need not be consistent throughout the groups of the firm.

The leaders we have seen who are most effective tend to have other leaders assist them who complement their style. For example, hard-nosed leaders who offend fragile temperaments often choose lieutenants who can smooth the waters in their wake. Similarly, detailed-oriented leaders need to ensure that there are visionaries on the team. Perhaps even more important, visionary leaders require detailed-oriented lieutenants who can ensure that the i’s get dotted and the t’s get crossed.

Black Holes and Bright Lights

Some of the leaders whom you appoint will protest. “You don’t understand! I must deal with some idiosyncratic and extreme personalities.” Many groups have within them individuals that might be referred to as “stars.” The relevant question is whether these stars are “black holes” or “bright lights.”

Bright-light stars illuminate those around them. If you think of your favorite sports franchise, you might be able to think of a player who not only has individual star quality but who seems to raise the level of play of the entire team as well. This is a bright light. Conversely, all too many of us can think of a stars who demoralize those around them and operate almost in spite of their team, or group, or firm, rather than in harmony with it. These are black holes.

Black holes, in physics, consume so much energy that even light cannot escape. The gravity is so intense that, at least theoretically, all matter occupies an infinitely small space. The relevance of the black hole or bright light analysis for your stars is to determine how they are to be managed. The bright lights usually do not pose a problem. Unfortunately, this may mean that they are under-managed

in favor of the squeaky-wheel black holes.

The issue with black holes is whether they can be neutralized. Some leaders refer to “black hole” individuals as requiring “high maintenance.”

Can you and the leaders who serve you afford the time, effort, attention that it takes, not to necessarily enhance the performance of the black hole, but rather to simply neutralize the impact so that he or she does not demoralize the team? To their credit, some black holes are easily neutralized. They simply need to be made aware of their influence, and to be asked by someone whom they respect to refrain from behavior that negatively affects the group. The quid pro quo is usually a certain amount of autonomy for the challenging individual.

There are, unfortunately, other kinds of black holes who seem to be unable to either understand or accede to such requests. These black holes are dangerous in that they will consume the efforts of the leader as well as negatively affect the performance of the group. These individuals are tolerated to the detriment of the group and therefore the firm. They should be isolated from the group as necessary or in extreme cases should be allowed to go and live somewhere else, their books of business notwithstanding.

Action Points

I suggest that you might consider the following action steps.

First, assess each current group and place it into The Discrimination Model. First, list each group in the firm. Using a forced choice method – i.e., you must decide! – rate each group on the receptivity/potential benefits axes that comprise the model. Then place the group in the appropriate quadrant.

The only guidance I can offer is that this is a time for “reality,” not “self-deception.” So, do the exercise alone. That will help you to be honest with yourself. This is not a committee decision. Earlier I mentioned that you will be judged for the accomplishments of the firm during your reign. It will be of little help to say, I knew what to do but the committee that advised me democratically forced me on the wrong path.

Second, consider the existing leader of the groups that fall into Quadrant 2. In particular, analyze their competencies and weaknesses against the leadership attributes listed below the model.

Third, manage these leaders by requiring of them that they take on assistant leaders to complement them, both in style and approach, and to alleviate their time burdens. If a Quadrant 2 leader is reluctant to accept such an offer of assistance, remove him or her as leader. You have far too much to lose, and too much to gain, to tolerate an uncooperative leader in the all-important Quadrant 2.

Having said that, you may be dismissing someone with informal influence and importance. If that is the case, it may be appropriate to give such individuals honorary roles; for example, making them chairpersons of the group but not its de facto leaders.

Earlier, I alluded to the tendency among lawyers to want to organize the firm as if drafting an agreement, with perfection and consistency, rather than by trusting your instincts. In this vein, a firm’s leadership should not be configured like a perfectly coherent legal document. As we’ve suggested, different leaders should have different roles, depending on the nature of their group. There should always be flexibility for each group situation.

For example, it should be quite tolerable for a firm to have a chair

of one group but a practice group leader

of another. Rigid conformity to consistency in titles unnecessarily restricts the discretion of the firm leader.

I hope that the analysis contained in this article will allow you to discriminate in a very positive and constructive manner. By determining where the greatest benefit from leadership might be, as well as where the greatest receptivity to such leadership might lie, you can concentrate your efforts on high-yield leadership appointments by knowing which leaders have the best chance to create success in your firm. You can more carefully select them and then more carefully manage them.

Do you abandon the other leaders? No. You just don’t let every proverbially squeaky wheel get your grease. My colleagues and I have often recommended that enlightened firm leaders create a council of leaders who would meet regularly to learn from one another. A small investment of your time on a monthly or, if necessary, bimonthly, basis–meeting with your leaders for a focused two hours, free of administrative distraction – can do a great deal to elevate the management competence in your firm.

By learning to be less demanding of those leaders who are in a caretaker role, in favor of being far more demanding of the leaders of areas that represent the firm’s future prosperity, you will be allocating wisely the most valuable resource of the firm.

That resource happens to be you, and your time and energy as its leader.

Ten Steps toward a Happier Firm

Nick Jarrett-Kerr I have been involved in the management of professional service firms for upwards of twenty-five years, and during that time much of my effort has been directed towards helping firms to develop and build what might loosely be described as “success” – strategic success, financial success, business development success, organisational success and positioning success (relative to rivals), as well as individual career and monetary successes for the professionals involved in the enterprise.

I have been involved in the management of professional service firms for upwards of twenty-five years, and during that time much of my effort has been directed towards helping firms to develop and build what might loosely be described as “success” – strategic success, financial success, business development success, organisational success and positioning success (relative to rivals), as well as individual career and monetary successes for the professionals involved in the enterprise.

Profit is of course key to the survival and prosperity of any business, and all the individuals in professional service firms are quite rightly focussed both on how to maximise the potential of the firm and how to achieve a sustainable, productive and effective organisation that adds value to clients and can appropriately reward its stakeholders. In this context, the topic of organisational culture, for instance, has concentrated on researching and analysing the dimensions of culture that have been found to make a difference in a firm’s success. The logic is that a powerful and positive culture can bring people together, serve as the glue that turns a bunch of individualists into a team, and fire up the firm’s members to perform better and more harmoniously.

Having said all that, I have not come across an enormous amount of discussion or analysis about what makes a firm happy per se – in other words what makes it a rich and harmonious place to work and hang out, regardless of the profit motive.

It might seem obvious that good leadership is a necessary element in any happy ship. Whilst in a crisis people respond to the imposition of martial law, a contented firm needs a more nuanced approach – a blend of determination and emotional intelligence. At the same time, nobody wants to be pampered for long or to live in an atmosphere where any sort of conduct is tolerated. Like parenthood, discipline with a lightish touch needs to balance out mere indulgence. Somebody told me quite recently that he thought that leadership and love overlapped a lot; certainly it helps enormously if the leadership group in the firm are passionate about the firm and what it does, and the leaders care deeply for the firm’s members.

In this article, I attempt to list ten steps that the leadership team can take towards a happier firm. They are based on facets of contented places to work that I have experienced or observed through the years. I am sure there are more! This does not set out to be an exhaustive academic piece but instead a set of reflections and suggested steps that lean entirely on my own experiences and observations.

Step One. Equipping for the Journey

The starting point for any journey is to know where you are going, how you are going to get there and the tools and kit needed for the journey. The objective of this step is that by investing in the office “ecology”, the office can become an awesome place to work.

Whenever I walk into the offices of a professional service firm, I am always struck by the atmosphere of the place, rather than the glossiness of the reception area. Some offices seem to radiate warmth and friendliness whilst others seem more clinical and lacking in energy.

There seem to me to be three features in which the happiest firms invest time and money. First, and most obviously, a well-trained set of reception and office staff clearly helps the visitor to the firm, so training members of the firm in soft as well as hard skills helps internally. Second, although a pleasant office may not be motivational, nevertheless an unpleasant place to work clearly demotivates. People may complain if a room is too cold but take it for granted and rarely enthuse when the temperature is just right. Hence, the obvious artifacts of office life need thought and care – the sort of attention demanded by enthusiasts of Feng Shui, for instance.

The third ecological element is the much vaunted, researched and analysed “organisational culture”, often described as “the way things are done round here”. I was once told by a managing partner of a law firm that he controlled the firm’s culture, but I think he was mistaken – the best anybody can do is to influence it (positively or negatively). A good way of doing this for for the firm’s leaders to be exemplars of the sort of positive cultural traits, values and behaviours that they espouse.This is a tricky area in which to invest – soft, long term, fuzzy and almost impossible to measure quantitatively.

Step Two. Stepping up Intercommunications

One of the most often heard complaints about an unhappy workplace relates to communication: specifically when it is poor, patchy, economic with the truth, or lacking transparency. There are some significant structural and emotional barriers to good communication in law firms. Teams, practice groups and offices can easily lapse into functional silos, with poor communications even between people on different floors in the same building. In addition, the concentration on maximising the billable hour and the drive to prioritise time generally, combine to reduce interaction between staff. The use (or misuse) of email, and stilted discussion at formal team meetings become a poor substitute for the easy interchange of ideas which can often take place in a semi-social setting. What is more, many firms have grown to the extent that fewer employees know each other. Whilst communication between friends is often difficult, communication between strangers can be fraught with problems.

The truth is that the traditional structure and hierarchies of professional firms do not lend themselves to a culture of easy communication. A ‘them and us’ tradition can lead to grapevines, rumour-mongering, suspicion, cynicism and muddled goals. In such an environment, many partners have difficulty in perceiving what their tasks and roles are, and how they are expected to contribute to decision-making.

The leadership team and the partners can also often find themselves singing from different song sheets and the fragmented results almost always have an adverse effect on morale. In response, there is a temptation to increase the number and length of meetings, memos, papers and e-mails, with less likelihood that the offerings will be read and understood. Conversely, some leaders continue to act on the premise that knowledge is power and purposely under-communicate within the firm so as to protect vital information and data from slipping out of their controlled grasp. Complaints about poor communication can also act as code for a general gripe about lack of involvement. What is clear is that much of the task for the leaders is painstaking, often process-driven, and at times downright boring. The clear message to firm leaders is that they should adopt a careful and methodical approach to their strategy for discussions, interchanges and information flows.

Step Three. The Long Walk to Collegiality

The assets of a “people” business tend to enter into and out of the office every day. Partnership relationships tend to be quite long term and although they are business relationships and not necessarily personal ones, they need investment. It is easier in this context to make a long list of the many mistakes made in firms in understanding and developing people. Closed doors, hierarchical thinking, displays of arrogance and self-importance, selfishness, impatience, intolerance of mistakes, eagerness to lay blame, morale-sapping behaviours, anger issues, bullying, sarcasm, disrespectful treatment of others, exploitation, unwillingness to listen, internal politics and jealousies are all features of unhappy firms where morale is low and where careers tend to be short-term. It is vital to realise here that the positive antonyms of the above list are formed by acts of will and matters of decision rather than by a feeling or a burst of emotions. Happy firms tend to be ones where the leaders and followers have made a conscious determination to invest in relationships, moderate their behaviours, and do their best for the collective membership and to individuals at all levels.

Step Four. Walking at Different Paces.

We tend to like people to be like ourselves. This can lead to intolerance of people who are different to us, and this can breed unhappiness. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn once observed that “it’s an universal law – intolerance is the first sign of an inadequate education”. The way in which the firm handles diversity is critical to the achievement of harmony – not just ethnic, cultural, religious or biological diversity, but diversity in views, opinions and behaviours. The key to the happy firm lies in understanding and making allowance for the very different ways in which people interact and behave as a result of their particular mixes of history, origins, upbringing, traditions and personalities.

Professional service firms are made up of many elements of diversity as well as different character types – extroverts, introverts, drivers, and thinkers are amongst them. People in firms tend to look at the world in different ways. Some constantly strive for results, some are laid back and amiable, some are analytical and some are process-oriented. People come across vastly differently as well – for instance, as dramatic, entertaining, sociable, closed, reserved, sensitive, submissive, or indecisive. None of these different approaches are necessarily right or wrong but there are at least two issues. First, relationships between diverse personalities can easily become toxic. Too often we fall into conflict and become critical when we expect everybody else to behave and interact just like us. The second issue is that strengths can become weaknesses; laid back people can become lazy, drivers can be dictatorial and perfectionists can become paralysed by their analysis. The disciplines of self-perception (and a desire to correct one’s own shortcomings) together with an attitude to others of understanding, appreciation and encouragement enable harmony to be achieved, strengths to be pooled, risks to be identified, and robust decisions to be agreed.

Step Five. Loving Curiosity

Conformity can have a somewhat deadening effect on the atmosphere of firms. All professional service firms need to have processes, systems, quality checks and compliance regimes. All of these are no doubt necessary for efficiency, risk management and regulatory control. However, I have often noticed how weighed down people often can feel because of the huge load of internal regulation, some of which can seem unnecessary. Morale suffers where there is too much unnecessary red tape. To quote Joseph Conrad, “The atmosphere of officialdom would kill anything that breathes the air of human endeavour, would extinguish hope and fear alike in the supremacy of paper and ink”. It is of course easier said than done to say that the compliance touch should be as light as possible, consistent with the firm’s overall objectives. Slavish and obstinate adherence to existing systems can however be avoided if firm members are encouraged (and rewarded) to be questioning, proactive and innovative in suggesting alternative approaches and new ways of doing things.

Step Six. Grinding Through the Pain Barriers

Happiness is not the absence of conflict. I have always loved the example of the grit in the oyster to illustrate the importance of constructive debate and the advantages of healthy argument on important issues. The tension between two valid points of view can often be tested and deployed to make decision-making better. Innovative ideas can be generated by the use of creative tension and energy. The problem is that in any discussion, bitterness, resentment and anger can easily set in and can be difficult to prevent when strong-minded personalities are involved. The key here is to engage with different points of view, and to tap into a spirit of healthy debate and commitment in order to find the best solution and to suspend personal stakes, ego trips and stubbornness. In meetings, this kind of engagement requires subtle and refined chairing skills. In individual instances of conflict that require intervention, diplomacy and mediation skills may be needed.

Step Seven. Engaging the Mavericks

The insistence on dogmatic convictions can lead to stagnation of ideas. Clients of professional firms appreciate the long years of experience that contribute to the skill bases of their advisers. It is of course good to rely on tried and trusted solutions to problems and challenges that are similar to ones that the firm has successfully encountered in the past. Pushed too far, however, reliance on existing approaches and solutions can lead to a stultified atmosphere where change is resisted at all costs, and new ideas suppressed or ignored.

In the last few years, some firms to their credit have recognised that innovation has traditionally been in short supply in professional firms. This is often because of the straight jacket of a billable hours’ philosophy that does not value time spent on exploring or creating new and different methodologies and emerging services. There is then a further question as to whether any mavericks at the firm are geniuses or jerks – many seem to have elements of both! I remember one partner who was extremely innovative and was constantly thinking up new ideas and plans, some good and some not. He was certainly not easy to get on with and, unless influenced by a moderating force, he tended to cause a lot of strife in the office. As always, there is a question of balance to be attained that cannot simply be defined by a recipe. Too much freedom and chaos (and unhappiness) results. Too much restriction of new ideas and stultification occurs.

Step Eight. Building Teamwork

Isolation breeds discontent. Law firms are one example of a professional services sector where some firms can be described as “motels for lawyers”, in which lawyers carry on a largely autonomous existence as sole practitioners held together by the glue of the compliance and professional regulatory regimes mentioned at Step 5. The same may be true to a greater or less extent of other professional service sectors. Such firms are not necessarily unhappy as such, but (apart from being in most cases commercially inefficient) can breed an atmosphere in which firm members are not encouraged or forced to build close ties with fellow members. Instead, people stick in their offices with their heads down and keep to their individual routines.

I have noticed that in such an environment people can often wear a mask or outer shell to hide their inner feelings of isolation, boredom and lack of career fulfilment. A culture can then easily grow in which everyone’s mask or shell condemns others to live the same pretence and keep their dissatisfaction a secret. There are of course many ways in which teamwork can be built – such as weekly team meetings, firm retreats, and frequent face-to-face interactions. In short, firms that I have experienced that try to be a “one-firm firm” seem (with some exceptions) to be more stimulating, contented and productive places to work than are “motels for sole practitioners”.

Step Nine. Looking up to See the Horizon

Corporate narcissism – where the firm constantly looks inwards and not outwards – is unhealthy and can imperil a firm’s state of well-being. I sometimes see firms where nothing seems to matter other than the firm itself. The firm lives in its own bubble and is both egotistical and egoistical – both feeling superior to others and preoccupied with itself. Clients become a tedious necessity, and the pursuit of unique or exclusive technical excellence is paramount. To some extent, these are excellent attributes if treated with moderation.

Nowadays of course firms are rightly required to embrace “corporate social responsibility” but often do so with a degree of hypocrisy or cynicism, to protect a sensitive client base or to assist in brand building. As a young lawyer, my then senior partner always encouraged us to give back something to the community by way of charitable work or towards a societal need. There are of course good business-building reasons for so doing – external involvements and networking are necessary to bring in clients and work. However, I have noticed that narcissistic firms seem to suffer a lack of oxygen and elements of claustrophobia that result from a refusal or inability to engage more than is absolutely necessary with the world outside.