A Talent Take on Law Firm Rankings

David CruickshankThe first quarter brings us rapturous reports of revenues, rankings and profits per partner from the U.S. legal press. American Lawyer Top 100 rankings are announced. Headlines like “30% Profit Increase at Firm Despite Pandemic” appear. And “rumored expensive deals” for lateral partners get favorable attention for the acquiring firm. This drumbeat from the legal press about “top firms” is supposedly a proxy for excellence in law firms, law practices and excellent individual talent. But are these the best measures to help a client or a job-hunting professional decide to choose a “top” firm?

How did we get here?

The U.S. legal business is unlike that in any other nation because it voluntarily offers up its financial numbers to The American Lawyer and other data aggregators who will publish (for profit) comparison tables that are principally focused on revenues, lawyer numbers and profits. There is no S.E.C., no regulatory body and no external shareholders asking for these data. You can’t get these numbers on law firms in Canada, Brazil or France. But it has become a “given” to discuss U.S. firm rankings as a proxy for excellence.

Some Alternative Measurements to Consider

The Client Perspective

It is true that some clients will choose a high revenue large firm because of its perceived excellence or AmLaw ranking. But that is often because the corporate counsel answers to a Board or executive that wants “the best” external legal talent. This provides a buffer if the legal strategy goes south. But why would a client choose the most profitable firm? That seems like a proxy for over-paying your lawyers, not necessarily excellence. Clients do value personal connections to lawyers who have demonstrated their talents and provide both value and excellent service. For that reason, it is often assumed that an excellent lateral partner hire will bring their clients with them. There is no ranking for “How many loyal clients-per-partner do you have?”

The Associate, Partner or Professional Hiring Candidate Perspective

It is doubtful that prospective hires make their decisions based on external rankings. True, a top student or mid-level associate might use rankings to create a pool of potential firms. However, they will put greater weight on their future co-workers, career advancement, training and business development opportunities when making a final choice.

Internal Talent Ranking Numbers

Most of these internal numbers are not available, because they are not shared or consistently reported. Yet, if a firm wanted to persuade clients and prospective hires of their excellence, value and a “best fit” for a lasting relationship, these are some numbers they might promote:

- Associate retention rates at years 2, 5 and 8

- Associate retention per practice group

- Professional position promotion opportunities per year

- Acceptance rates from the ten law schools where the firm most often competes for talent

- Percentage of budget spent on talent, CLE, training and mentoring (of administrative budget) and year-over-year changes over 5 to 10 years

- Average and high/low of partner hours per year recorded for training and mentoring

- Lateral hires incoming (partners and associates) per year, last 5 years

- Departures of laterals who were with the firm less than 5 years (compared to laterals who “stick” longer than 5 years)

- Diversity hire increases/decreases over 5 years

External Rankings

External rankings turn on surveys and perceptions of employees. When taken annually or every two years, these can show that a firm is on a rise or a downslope where employee satisfaction is concerned. Two measures that get a lot of attention from those who work in recruiting and professional development are:

- The AmLaw Mid-Levels rankings

- Fortune 100 Best Places to Work (annual, covers all companies).

These rankings are more likely to be seen by clients, since firms will promote the rankings in their websites and newsletters. The 2020 rankings will reveal satisfaction with early handling of the pandemic. In the AmLaw Mid-Levels survey for 2020, O’Melveny & Myers was the top ranked. When compared to all companies and professional services firms, it is tougher to place in the Fortune 100. Yet Alston Bird, the first law firm to break into those rankings, is a perennial top 100 choice of employees. Perkins Coie was the highest ranked law firm in 2020 and 2021. Only 3 or 4 law firms make the Fortune 100 every year. Orrick regularly ranks well in the Fortune 100 and appears in the top 75 of the AmLaw survey.

Conclusion

Whether you are a client looking for excellent lawyers or a jobseeker looking for a great place to work, the much-touted rankings for revenues and profits may be the wrong proxy for excellence. Excellence may be better measured by how much investment a law firm makes in its people, how long they remain at the firm, and how the employees, from first hire to longer career paths, rank the firm. A law firm that is not ranked highly in revenues and profits might turn instead to showing how they excel on internal measures of career development and external rankings by employees. There’s a unique competitive advantage if your measurements make your firm a talent magnet.

Four ways to Ensure Success in Hiring New Partners

Nick Jarrett-KerrLateral hiring in professional service firms has an uneven track record. Statistics consistently show that hiring a ready-made partner from another firm often results in disappointment both for the firm hiring them and in terms of the new partner’s own expectations.

There are four main tactics to avoid the usual traps.

Tactic One – Get the Business Plan Right. One principal reason for failure is that the new partner’s business plan misfires. Even glossily prepared plans can prove to be unrealistic over optimistic. The Partner may expect to bring over clients or staff and everybody is disappointed when these arrivals do not actually transpire. That is often because the old firm manages to take steps to protect its client base and because team members often decide to stick with the old firm. Hence it is important that the business plan of any new hire should be tinged with a large dose of realism. Even where the plan is realistic and sensible, firms and their new partners often mutually misunderstand how long it takes to bed the partner in, to move to full productivity and to generate revenue and cash flow.

Tactic Two – Choosing the Best Partner. Failures can occur when the firm is blinded by what the prospective new partner can bring by way of client following or specialism. The firm then fails to take the necessary steps to ensure that their new partner is someone who will fit in to the firm. Proper on-boarding processes are important to ensure that the new hire is left with no opportunity to hide away in a corner or to operate as a sole practitioner within the new firm. Some lateral hires seem to make little or no effort to espouse the new firm’s behaviours or to take part in firm activities. Care should therefore be taking in the early on-boarding and induction processes to gain early warnings of possible trouble. Particular attention should be paid where there is any risk that the new partner might tend towards being an individualist “lone wolf” who may find it hard to fir into the firm’s collegial culture. Conversely, where the culture and values of the firm stress and reward individual effort over team performance, persistent communication channels may be required where new partners are used to working as part of a team and consequently might struggle to be left entirely to their own devices.

Tactic Three – Form and Execute an Integration Project. In tightly knit firms, practice groups, used as they may be to their own friendships, informal rules and patterns of behaviour, can find it difficult to admit a new person to their inner circle and hesitate to make insufficient effort to integrate new people. The new partner may try to force his or her way in but find it easier said than done. I hate to say it, but many groups still suffer from latent prejudices when faced with new partner from different backgrounds, diverse ethnic origins or even different genders to the majority. Some firms can still be categorised as bastions of white male privilege. In this connection the firm’s leadership can often give a firmer steer to communicate both the standards of behaviour that are required and the ingredients for integration success. The integration project should be treated both as a change management program and as a team building exercise. It sometimes helps to use a cultural inventory to create action plans and to work out areas of difference between the practice group and the new partner which may need development. In this connection the project is not finished and cannot be signed off until you’re absolutely sure that you can say “he or she is truly one of us“

Tactic Four – Ensure Appropriate Support from the Firm. Professionals should of course be self-starters, but some firms are too quick to adopt a “sink or swim” attitude to new hires. It is about twenty years since I was a managing partner, but we introduced a rule that we would always try to find the first engagement for the new partner from the firm’s existing resources and client base. This was partly to ensure that the new partner felt welcomed but also to assure new partners that we were not expecting them to rely entirely on their own efforts. Support can also be missing if the firm turns out to be the wrong platform for the new partner – I recall one experience when my firm hired a pensions partner to a practice which had insufficient client or work type synergies to enable the new partner to thrive.

The brutal truth is that despite all efforts not everybody will always fit in or be successful. However, it is seldom too late to work on integrating new people and it is worth checking with recently hired partners how firmly are woven into the fabric of the firm and what more can be done to enhance relationships.

Integration Or Disintegration, That Is The Question

Leon SacksThe objective here is not to be alarmist or suggest that there is a binary choice between life or death, as in Shakespeare’s allusion. It is, however, meant to draw attention to the need for continuous focus on what keeps a professional services firm, and more particularly a partnership, ticking and successful, namely the integration and collective behavior of its partners.

Integration means that partners are working in the same direction towards a shared goal, that that they are aligned in managing their teams and representing the firm and that their capabilities, knowledge, experience and relationships complement each other.

Disintegration is a danger when there are conflicting priorities amongst the partners and divergent opinions about the way business should be conducted and individualistic rather than collective behavior becomes prevalent. The partners or groups of partners become isolated and unhappy and the firm may become a composite of fiefdoms rather than a homogenous unit.

The current reality of disruption with rapid changes in demand and supply chains is challenging leaders and management in the corporate world. In a partnership such challenges are often magnified by the fact that partners consider themselves co-owners of the business, desire to have a say in how business is conducted and wish to share the benefits.

While overseeing the quality of work, client relations, finances, talent, business development and efficient operations, management needs to be attuned to the concerns, motivation and behavior of partners that, untreated, might be detrimental to the achievement of goals in all those areas. Just as a relationship of a married couple needs to be managed so does a partnership, except that in the latter case the marriage counsellor has to deal with multiple people!

Clearly management deals with partner issues on a daily basis and often this means putting out fires and/or spending a great deal of time in managing people’s expectations or explaining why a certain decision makes sense. Issues will always arise but would it not be more efficient to have integration as a permanent item on the agenda knowing that it will require continuous action as the firm grows and changes and as its partners’ careers advance and ambitions change?

Conditions that might indicate the need for greater integration efforts include:

- partner grievances or departures

- extensive partner discussions on strategy, structure or processes

- incompatibility between partners

- doubts raised by partners about contributions of others

- reduced partner performance or motivation

- unsuccessful lateral integration

- reduced retention rates of attorneys

- individual v institutional behavior

- offices or practice groups working autonomously

- different approaches to service delivery and client management

- little or no sharing of information

- “my clients” attitude prevails rather than “our clients”

- partner compensation system not perceived as fair

- complaints of excessive centralization or lack of flexibility

- inconsistent quality of service perceived by clients

These conditions might not have been a common trait but as a firm grows, the partner ranks grow, the number of offices/practices grow and the firm adapts to market conditions, they may develop quickly. If they are not isolated and become a pattern, management needs to evaluate the causes and adopt a remedial action plan.

As suggested earlier, it is preferable that this be done on an ongoing basis taking the temperature of the organization and the status of the partnership on a regular basis and adjusting accordingly – what we might call the integration “agenda”.

The integration agenda should aim to ensure:

a) Partners are “supporting sponsors”

The alignment of partners with the vision and strategy of the firm and their consistent adherence to common and agreed-upon principles is key to leading the firm in the right direction. They should all be supporting sponsors of the firm’s direction and communicate a consistent message in that regard. Partners are largely the face of the firm to clients and its professionals and their behavior weighs heavily on the way the firm is perceived.

b) Strategy drives structure

Whatever the message for integration, if a firm’s structure drives behaviors that are not aligned to that strategy, it will not succeed. As the Harvard Business Review once stated “leaders can no longer afford to follow the common practice of letting structure drive strategy”.

A crude example: if two offices of a firm are organized as two business units with their own local management and the partners in each office are compensated largely based on the results of their own office, a strategy of sharing resources and cross-selling might be prejudiced or, at a minimum, not incentivized.

c) A collaborative environment

Collaboration generates internal synergies (e.g. sharing talent and knowledge) and external benefits (e.g. client development) while allowing partners to feel more connected to each other, reduce their levels of stress (hopefully!) and enjoy more work freedom. Incentives and support for collaboration that reflects a more institutional approach to conducting business are to be encouraged. This is by no means inconsistent with an entrepreneurial approach to business or rewarding individuals for extraordinary performance.

It is not uncommon to find firms consisting of different groups or individuals that are somewhat autonomous, take different approaches to service delivery and client development and work largely in isolation from others (the “composite of fiefdoms” mentioned earlier). This is rarely a pre-meditated or deliberate action but rather derives from different cultures and work habits (resulting from previous experience in other organizations) and behaviors driven by the firm’s governance and partner compensation system (i.e. what is my decision-making authority and how is my compensation determined).

To be an “integrated” firm, a firm that is effective in providing solutions for clients and is efficient in its use of resources, it is imperative to create a unified culture and adopt governance and compensation models that motivate a one firm approach. Consequently, principles that typically underpin integration may be summarized under three headings:

Governance

- the governance and decision-making structure be clear and understandable

- the management structure reflects diversity of practices and offices, but with all decisions aligned to the firm’s strategy and to the best interests of the firm as a whole

- the governance structure reflects the importance of practice and industry groups as natural integrators across offices and jurisdictions

- authority and policies for decision-making be delegated as appropriate to avoid shackling the organization while allowing for risk mitigation

- Committees and task forces with appropriate partner representation deal with ongoing issues (e.g. Compensation Committee, Talent Management) and specific projects (e.g. Strategy Review, Remote Working), respectively

- a partner communication structure that allows partners to be continually informed and feel they are being consulted on issues of relevance to the business

Partner Compensation

- the compensation system provides clarity on expectations of contributions from partners and aligns compensation with such contributions

- adopt the right mix of compensation criteria to motivate and reward both behavior that drives the firm strategy (revenues, originations) as well as collaborative behavior that encourages teamwork and partner investment in the growth of the pie, rather than a struggle for a larger share (cross-selling, training initiatives)

- couple the collection of objective data with subjective inquiries to adequately measure partner contributions and allow for appropriate discretion in applying compensation criteria to promote fair and equitable results

- consistent partner feedback process

Leadership

- build and support a culture with a shared mission, joint long-term goals and shared risks and rewards

- align structure to strategy, clarify roles and responsibilities and enforce accountability

- promote transparency and open communication and be inclusive

- build trust and confidence facilitating interaction between partners and creating a healthy dose of interdependence amongst them

Firms can easily lose the focus on integration, an intangible asset, while they are busy dealing with the tangible issues of day to day operations, developing business, serving clients and controlling finances. It is better to manage integration than recover from disintegration.

A Simple Governance Framework for Small to Mid-Sized Law Firms

Sean LarkanI am quite frequently asked for advice on what the ‘ideal structure’ is for the typical governance set-up in a small to mid-sized firm. By “governance set-up”, we mean the leadership, management and decision-making structure of the firm; who or which body is responsible, is accountable and has the authority to do and decide on various matters.

Some initial research and discussion with existing leadership will determine how one should tackle this in a particular firm:

- What is the existing leadership, management and decision-making structure, and how is that viewed as functioning? For instance, is there a managing partner or general manager in place? Is there a board and/or some form of executive or management committee? Are managers or partners in charge of client-service and support-service areas?

- What are present expectations around contributions by partners – e.g., covering items such as financial performance, financial management of own practice and teams, business building and marketing, client-relationship management, brand building, building the firm’s capital fabric, or people management, to name a few?

- How hands-on or hands-off are the partners presently in relation to management and decision-making? What level of communication do they feel they need? What is their thinking in this regard?

- What is the present positioning of the firm in its market, and does it have a clear vision and strategy? Is it in a strong position, facing big challenges or wanting to grow, and so on?

- What is the culture of the firm and what are the engagement levels of staff and partners?

I have found from personal experience running mid-size to large firms for twenty years, and consulting to such firms for the past decade, that:

- It is more helpful to think in terms of having a flexible governance framework than a governance structure as such. One can use the framework to deal with the needs of a large majority of firms, each with a slightly different make-up and priorities;

- Given the large number of diverse challenges and the important types of contributions expected of partners to succeed in practice today, one should ideally wean them off being involved in all decisions and firm management, especially those matters relating to day-to-day management.

With the above in mind, I have found the following framework and simple set of guiding principles worthy of consideration:

- Start by reserving a limited number of strategically important topics (e.g., exiting a partner) for decision-making by the owners/equity partners;

- If necessary, reserve some items to be signed off by the partnership as a whole, but only once the board (see below) has already signed off on them, such as firm-wide strategy, annual income and expense budget, a new lease, and the like. Instead have partner meetings focus on practice-group and industry-sector strategies and business-building initiatives, in each case under the direction of the practice group or industry sector leader. Partner meetings should also be a forum for communication by the managing partner, senior managers, practice and industry sector heads, and so on;

- Reserve a small number of items (so-called “strategic matters”) for board or management committee attention/decisions. If it is decided to have a management committee or board, preferably have just a board (and keep it as small as you can get away with, and elected), not both a board and a management committee; otherwise, confusion invariably reigns and this will lead to frustration for a managing partner or CEO;

- On the support-services side (IT, human resources, marketing and brand, finance and information management) when a firm can justify it, I suggest dedicated, highly capable managers be appointed for each area, reporting to the managing partner. As the firm grows, consideration can be given to appointing a general/practice manager who would then take on oversight of other support-service managers. A variation on this theme, which I don’t encourage, but which has worked for some of my clients, is to have an interested/qualified partner in charge of each area;

- Below that, if a managing partner or CEO is the right person, they should be responsible/accountable for the rest, with a communication/consulting/delegation-upwards role vis à vis the board.

This makes for quite a simple, short governance structure with built-in flexibility. The benefit is that the structure is clear to everyone, and everyone knows where the buck stops: where responsibility lies, and who is accountable. I have seen this work very well, in slightly varying forms, in three firms I ran and also many to which I have consulted. It can be tweaked from year to year on review to suit changing needs or circumstances.

This simple solution avoids the need for drafting lengthy and detailed governance documentation covering all aspects of decision-making at different levels of authority and so on; in reality, these documents usually get settled after countless meetings and hours of discussion, sometimes involving the whole partnership, only to gather dust in some filing cabinet and seldom be consulted. Obviously, some firms might need or want to have more detail determined upfront about some areas of the above framework; one such example is the powers and duties of a management committee. These should be the exception rather than the rule.

For some, such frameworks take some getting used to as they keep partners from getting involved in day-to-day management and interfering in a lot of things! However, as noted above, there is so much for partners to get on top of nowadays they shouldn’t have time to get into this anyway.

Successful Strategy: The Essential Supporting Acts (Part Two)

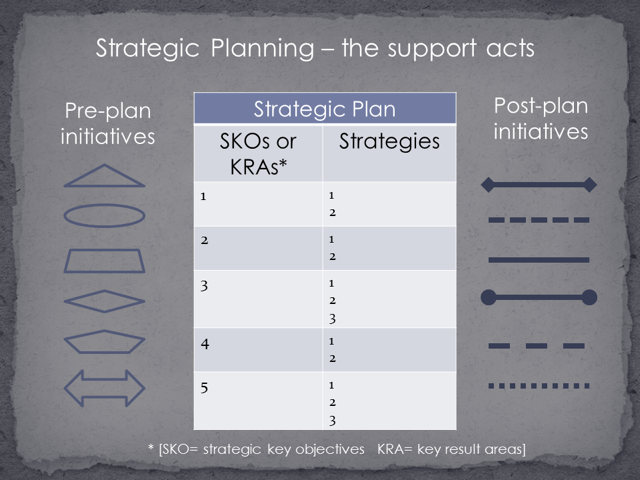

Sean LarkanIn Part One of this article, I focused on some important pre-strategy initiatives which should be tackled to lay a sound foundation for successful strategy implementation.

Here are some others:

Key governance structures

Fundamental to strategy success is a cohesive partner effort and involvement. It is not something that can simply be done and driven at EXCO/Board or MANCO level. But there are still many firms that have not yet tackled fundamental structures like clarifying what is expected of partners – contribution and performance criteria, and how feedback around meeting those criteria should be gathered and fed back to partners. In some cases this may come with consequences, depending on the basis of your partner equity structures – meritocracy, lock-step or managed lockstep and so on. Depending on the culture of the partnership this will usually flow into partner performance management or feedback, support and development systems.

Get these in place and there is a much greater likelihood you will get your partners focused on assisting to implement firm strategy – after all, it will be a key contribution requirement and criterion for partners and they will be measured on this.

Decision-making

In some cases you may need to streamline decision-making structures in the firm. There are still firms, and quite large ones, who go through a laborious process of having partners review and agree upon virtually every decision of consequence about to be taken by a leader or management executive. Strategy requires decisions being taken, and decisiveness. It usually calls for partners to relinquish some control and decision-making powers to their managing partner/director.

Key information systems and management structures

Once you embark on a strategy exercise, and finalise partner performance management or feedback and development systems for partners, your information and support service management structures and personnel should, and will, be tested to the full. Where possible (in the time available), it is wise to vigorously review these at this early stage to ensure they are adequate and ready to support your strategic initiatives. Otherwise shortcomings here can in themselves cause strategy implementation to stumble or even fail.

The strategy document itself

As noted in Part One to this article, keep the document “lean and mean.” I would suggest limiting this to a short summary of your Core Purpose (however you decide to constitute that), your strategic key objectives (or call them “key result areas”) and key strategies.

Don’t bog it down with too much detail or layers of actions, time-lines and responsibilities for all and sundry in the firm. The detail can come later in the form of implementation plans by task force Leaders, practice/industry group heads, senior support service managers or even partners in their individual business plans.

The reason for this is that you want your strategy walking around in the heads of every partner and manager in the firm. This will only happen if it is short and punchy.

Too often the process of finalising the strategy is dragged out for far too long. As a result partners are lost along the way and interest in and support for the strategy initiative slips. Keeping the document short and focused on truly strategic issues assists greatly. You can test all your strategic key objectives by asking “Will success in achieving this objective have a massive impact on our firm?” If not, it is not strategic and shouldn’t be in your strategy. You will need to be vigilant as partners and managers will invariably try to bring in non-strategic albeit important items on to the list for attention.

Post Strategy

Strategy is good strategy when it works and gets results. You will need to spend most of your time on post-strategy exercises, which is contrary to what happens in most firms. By this point many are too often “tired of strategy”!

Task Forces

I find the simple structure of a very small task force (not a committee) headed up by one driven, energetic partner or support service manager can work wonders. They should report directly to the managing partner on implementation. Where appropriate, short implementation plans can be useful, provided they don’t become bigger than Ben Hur.

Other strategies

Bear in mind that successful firm strategy often runs into or requires other sub-strategies for success. These may include a People Strategy, Finance Strategy or even a Brand Strategy. It is important these follow the same principles and are carefully aligned with the main strategy.

Partner feedback and performance-management systems

This is where these systems come into their own, post-strategy. Partners should receive feedback on and sometimes be measured (depending on the natures of your partner structures) against how they contribute to the strategy-implementation phase.

Keep your strategy alive – stress-testing

Most of the benefits of strategy come not in formulation but in stress-testing and fine-tuning it along the way. Be sure to do this at regular intervals – annually or at most twice annually is usually enough.

There are many reasons for this – reporting successes or problem areas, keeping partners interested and motivated and adapting to changing market conditions. Strategy is a living animal, a journey rather than a destination, and one which never really ends, as firms adapt, strategise further and move on to new things to compete effectively – and ideally, to dominate.

Strategy on its own does not achieve success. It is rather everything that goes with strategy to ensure its success.

I hope these ideas will prompt readers to consider what these things may be in the case of your firm. Each firm will be different – as to culture, structures, stage of development, strategic prerogatives – and these will determine how you tackle and support your strategy to successful implementation and results.

Successful Strategy: The Essential Supporting Acts (Part One)

Sean LarkanBehind successful firms is some form of successfully executed strategy. It can be short, punchy, even informal and, at a push, in someone’s head! The test is implementation and results, which always separates success from failure.

Strategy is not simply about ‘doing things better’; it is about achieving serious competitive advantage. It is high level, not operational or administrative.

The strategic plan itself is a relatively small part. It must be reinforced with many other supporting acts.

In this series of articles, aimed at small to medium firms starting out or wanting to upgrade their strategy process, I will outline some of these supporting exercises. If they are not undertaken it will seriously undermine a firm’s chance of getting results from strategy. Leaders will be challenged here – professionals like to jump straight into ‘doing stuff’: i.e. implementation.

The Strategy Document

The plan itself is often viewed as ‘the strategy’. In fact it is only a concise summation of key things that are sought, and, at a high level, how they will be achieved. Keep this document short and punchy. The strategy document must also be kept alive; it must be regularly updated.

But let’s consider some essential steps, ‘pre-strategy’.

Get your Partners Involved – from Inception

Get the partners involved upfront. This gets their support, shows them respect, generates ideas, identifies issues dear to them and improves chances of success and involvement down the line.

You must maintain their interest over a sustained period. They need to know how their role and contribution is valued and will make a difference. This is no easy task, but must be done. It requires real persistence. Keep your partners involved and interested but do not use too much of their time or bore them. This is a real test of leadership, as strategy is a journey not a destination and always a fine balancing act. It never truly has an ‘end’ and takes many twists and turns along the way.

Start by asking some searching open-ended questions based around the tried and tested SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities or threats) framework but also covering ‘core purpose’ items mentioned below. Also ask ‘What is going well?’ and ‘What could we do better?’ Challenge the partners to think about what in the firm:

- it should ‘stop doing’ (e.g. a loss-leading practice area);

- exhibits unrealised potential (e.g. taking advantage of existing client relationships);

- are substantial hidden expenses (e.g. less than full utilisation of expensive legal or support staff).

Do this ‘one on one’ or via a survey, but keep it short, punchy and relevant. Be sure to revert with survey outcomes or at least a summation of key points. Your job is to keep them interested and involved. By consulting, communicating and showing respect you do this.

Core Purpose or Strategic Intent

There is no single way to deal with concepts such as ‘core purpose’ but there should be a structure to it. I like to think of core purpose as clarifying your vision (what you want to be or where you want to go), what kind of firm you will be (e.g. ‘managed’ lockstep), your key cultural attributes (how we do things around here), your values (beliefs and understandings of what you will tolerate and not tolerate), what legal practices you will undertake or industry sectors you will focus on and the locations where you will choose to do this. Get these clear up-front and you will have set a very nice foundation for what is to come.

This is yet another test of leadership as this is arguably the most difficult thing around which to maintain interest. You will be met with all the usual scepticism, cynicism and sometimes downright objection. You will have to work your way through this.

Another thing I like to do early on is combine the values and cultural attributes exercise into ‘guiding principles,’ an idea I got from Norton Rose. Guiding Principles is a simple concept everyone can understand and it simply seems to make sense to professionals, which is half the battle. Otherwise, you will forever find partners or staff confused by concepts such as values and cultural attributes and what they mean. It is another little step in trying to keep things simple.

I look forward to communicating further in subsequent articles on this important topic!