Why Partner Integration Should Be On Your Agenda

Leon SacksPartner integration signifies that partners are working, both individually and as a group, in a manner that optimizes firm performance and is in consonance with their expectations.

Firm management is customarily occupied with monitoring the project pipeline, the productivity of professionals, client satisfaction, hiring the best professionals and winning and managing work. These are considered key contributors to a firm’s performance and success. However, partner integration can be an element of even greater significance to a firm’s performance and cannot be neglected or taken for granted.

Any sub-optimal performance at the partner level can have a multiple effect on the performance of the firm. This is because partners inevitably assume some management responsibility, whether managing a practice area, overseeing a group of professionals, handling certain client relationships or developing services and new business.

Partners consider themselves “owners” in the firm and, at a minimum, feel they should have some influence on how the firm is governed and managed. To the extent that is not achieved it can lead to dissatisfaction, a lack of motivation and even disruption, resulting in a significant, and often costly, distraction for firm management.

Do any of the following symptoms of a lack of integration sound familiar to you?

- complaints that a certain partner is not assuming his/her responsibilities or is not contributing sufficiently

- partners whose shortcomings (e.g. poor relationships with subordinates or lack of collaboration) are overlooked because they have good financials

- partners whose contributions are overlooked because their current financials are poor

- practice groups or business units operating autonomously and, perhaps, with distinct and even incompatible approaches

- lack of trust among partners reducing cooperation

- communication gaps between firm management and the partners at large, causing misunderstandings

- dissatisfaction with the fairness of the partner compensation system

- no effective performance evaluation process for partners (including feedback) leading to accommodations and misalignment

- partner promotion and advancement based on longevity rather than performance

- partner concerns as to lack of participation in decision-making

- controversial partner meetings without resolutions (disagreements allowed to fester)

Some of these situations may be overt (i.e. self-evident) while others may be covert (i.e. they exist but are not perceptible without specific questioning or analysis). All of them are examples of potential deficiencies in partner integration.

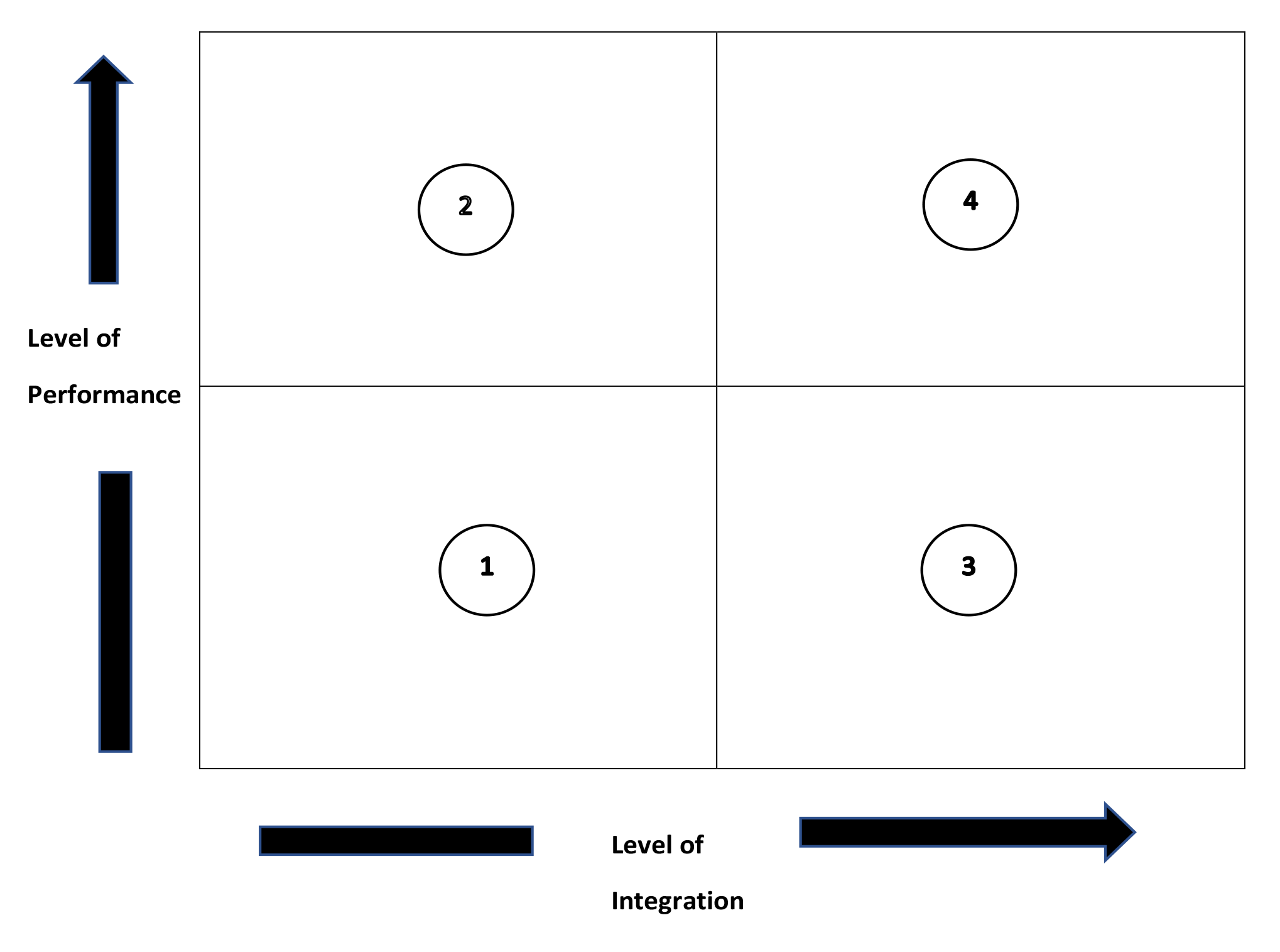

Where is your firm on the performance/integration map shown below?

Clearly performance and integration do not have unique definitions. They are a function of the values and objectives of a firm. Their measurement is dependent on an evaluation of a series of characteristics, many of which are qualitative rather than quantitative.

For example, performance may not be based purely on revenue growth or levels of profit but also on levels of client satisfaction, growth in certain service areas or practices and retention rates of professionals and/or clients. Similarly, integration may include evaluation of such elements as time spent on partner issues, level of partner satisfaction, client feedback, level of cross-selling and partner turnover.

Can you plot your firm’s position based on your interpretation of the level of performance and integration? Experiment doing this before reading on.

Let us now analyze the potential (common?) characteristics of firms in each quadrant of the map as indicated below.

Quadrant 1 LOWER PERFORMANCE/LOWER INTEGRATION

- Start-ups

- Group of disconnected partners

- Lack of management

- Unsuccessful merger (lack of trust/inability to change)

Risk: disruption, loss of partners/associates

Opportunity: improve financial returns, motivation and lifestyle

Quadrant 2 HIGHER PERFORMANCE/LOWER INTEGRATION

- Star individuals/practices run separately

- Group of autonomous units – perform well individually but focused on own P&L

- Lack of governance

Risk: loss of stars and/or practices

Opportunity: collaboration/synergies/cross-selling/joint client development

Quadrant 3 LOWER PERFORMANCE/HIGHER INTEGRATION

- Too nice – lots of “sticking together” but lack of drive/management discipline

- Tolerate non-performance

Risk: retention of performing partners, lack competitive advantage, lack of growth and retention of professionals

Opportunity: high growth opportunity and competitiveness

Quadrant 4 HIGHER PERFORMANCE/HIGHER INTEGRATION

- Uniform practices and strong financials across the board

- Smooth working relationships and stable governance structure

- Healthy interactions and high degree of trust

Risk: low risk of partner issues or defection

Opportunity: focus on growth and development and market leadership.

Clearly Quadrant 4 is the place to be by maximizing opportunities and minimizing risks. There is no perfect firm and there is no such thing as zero risk, but moving toward the top right corner of the map should be on any firm’s agenda.

That move would consist of making adjustments to the firm’s structure, policies and procedures, its mode of management and partner expectations. These may be included in a Partner Integration Program (“PIP”) that could then evolve into an on-going process as the subject matter is fluid and requires monitoring.

A PIP may address the following, amongst other needs:

- Promotion – promoting the right people facilitates integration and avoids costly mistakes. Promotion based only on the need to retain expertise and certain competencies may not be appropriate and alternative career paths are an option.

- Training and orientation – alignment to strategy, provision of skills to progress and motivation to grow

- Partner performance expectations, measurement and feedback

An effective partnership does not mean that all partners need to contribute in the same way but rather that the individual strengths of a diverse set of partners are used to maximize the strength of the partnership as a whole.

- Partner compensation – a system that recognizes the relative contributions of partners and is seen to be fair

- Adequate governance structure, leadership and communication channels

- Strong cultural glue

- Incentives for collaboration

A PIP will consist of the following phases:

- Define the components of partner integration to be measured

- Develop a plan to collect data and information for measurement

Remember that certain situations may be covert and therefore, to be complete, any diagnosis should include some form of consultation with the partners themselves (interviews, surveys, etc.). Such consultations should be conducted by persons independent of management so as to avoid conflicts and not constrain responses.

- Perform an evaluation of current status for each component

- Summarize findings and recommended actions for improvement

- Discussion and approval of action plan for implementation

Given that recommended actions will likely have a significant impact on partners’ roles and involvement with the firm, it is considered imperative that partners be consulted before any actions are approved.

I would be delighted to explore further the idea of implementing a Partner Integration Program, (PIP) should it be of interest to you.

How Can You Reach and Recruit Diverse Lawyers?

Mike WhiteI’ve been gobsmacked by how many managing partners and firm practice group leaders tell me, “Mike, we’re having trouble recruiting a homogenous, non-diverse stable of lawyers; we want to grow our numbers but we can’t seem to break the cycle of onboarding lawyers who all look very different from each other and represent different life experiences, ethnicities, geographies and genders. Can you help us address this human capital challenge?” Alright . . . so I’m not hearing that! As you might assume, I’m hearing quite the opposite. Outpacing all other law firm laments- by a wide margin- is the frustration firms express about not being able to recruit successfully enough diverse and minority lawyers.

Why can’t firms win more than their fair share of recruiting battles for diverse lawyers, and why is this important? For one thing, culture matters to all lawyers- both diverse and non-diverse lawyers. Lawyers want to work in eclectic, stimulating environments. Non-diverse lawyers are a flight risk if they are denied the affirming experience of working with colleagues who represent true diversity. Moreover of course, corporate law departments for some of the same reasons want to work with a more diverse stable of providers and advisers.

The legal business is a human capital business. With GDP growth at 6x-7x normal rates reducing to “only” 3x-4x normal rates as the economy recovers, demand for commercial legal services will remain brisk for a long time. The challenge law firms face in recruiting diverse lawyers is in some respects a more acute form of the challenge they face in recruiting all lawyers. What diverse lawyers want to see in a firm to which they commit their career in many respects is what all lawyers want to see in a firm worthy of career commitment. Compensation of course is important, but what else should firms support to more reliably attract the most desirable lawyers to their firm?

Career Long Commercial Success

Make an explicit and detailed commitment to helping your diverse lawyers be successful commercially. Many firms view the path-to-partnership as a 10-year fraternity hazing experience- “we want autodidacts who can figure out success on their own- that’s our partnership readiness KPI.” What if you were simply better than your peers at teaching your diverse stable of layers the functions and vocabulary of business so they will have an easier time engaging with client prospects? What if you taught them from inception how to cultivate relationships, convert opportunities into paying engagements, and cause third parties to become introduction generators for their pipeline? I encourage my clients to demonstrate with concrete, tangible and packaged deliverables what their competency building experience at their firms would look like in these areas- you must show that you are as intentional and serious about building in them these skills as you are about building in them technical legal skills.

Help Them with Life

Committing to a law firm career = committing to an imbalanced life. Help your diverse lawyers- particularly if they’re new to the community- build their supportive personal scaffolding so they can be even more effective at building their career. Get to know them and help them manage some of the non-work dimensions of their life that are rendered more complicated because of work. Do they want to send their kids to private school? If so, put them in touch with other partners who know something about that process. In what activities outside of work do they and their spouses/partners like to engage? Put them in touch with others who engage in those activities. How are they trying to build out their personal and professional network? Put them in touch with other firm lawyers who know people who would be interesting to them. Listen and learn, and then be helpful- pretty simple, huh? You should document what the firm does in these areas, and package it up (promote, educate others, and document) so that diverse recruits see that it is part of the firm DNA.

Educate Them with Expectations and Possible Roles

Many firms offer multiple paths and have cracked the code on how each flavor of lawyer can generate firm profits. Very few younger lawyers have a granular view of success over time at a law firm. We all know law firms can support thoughtful long term tracks for non-equity partners, fractional lawyers, and lawyers moving into business roles. Success in a law firm career is less binary and more complicated now. Firms expect to generate profits from all lawyers, no matter what title they have. All lawyers- including diverse recruits- need to understand what those roles look like and how they could be successful in each one.

Stop Being Cryptic

Many firms aren’t very open about what life will be like at a firm as a senior partner, or even as a young partner. AmLaw rankings may provide transparency into the financial benefits, but even those numbers don’t tell the whole financial story; e.g., amount of capital contributions, spread between highest and lowest compensated partners, what are the “doing my part” expectations at each stage. Also, be open about what people earn and why. You have much a better chance of convincing a desirable recruit to defer near term compensation gratification if they see a pathway to great financial security and reward down the road- but you must be specific and transparent here!

Control

Most lawyers care very deeply about blunting the imbalanced nature of law firm lawyering over a career by seeking control over what they are doing. “If I’m going to have to work this hard, I want to be able to do it on my terms . . . “ At bottom this means they need to see how they will build a client base of their own. How else could your firm help diverse lawyers establish control over their career- both long term and day to day?

If your firm is like 90% of the AmLaw 200 law firm that can’t throw more money at diverse recruits than your competition, then you have to be more thoughtful and holistic, if for no other reason than because your most desirable minority and diverse recruits bring their own thoughtful and holistic lens to these issues. Meet your human capital where they are, and give their long term career aspirations an intellectual bear hug- then you will begin winning more of these talent battles.

Coaching For Lawyers: Transforming Emotion To Energy In Motion

Bithika AnandWorld over, one-to-one coaching is a highly effective method used for achieving better performance. While coaching has been an extremely popular concept across the globe, in India coaching for lawyers has started to gain importance over the last few years. Keeping in mind this recent growth of coaching for lawyers in India, this article aims to discuss how coaching for lawyers can be a catalyst to their growth and evolution through the stages of career transition while also promoting workplace confidence, wellness, resilience, and mental strength.

THE CONCEPT OF COACHING

Coaching is a transformative conversation – a conversation that involves listening, exploring, bringing awareness, and making choices. It is focused on the ‘coachee’, i.e., the one who intends to change the status quo. A coachee is the one looking for a change – this could be something as macro as a quest for personality transformation or reaching a goal; or this could be smaller bite-sized initiatives like pursuing a hobby or aiming for fitness, etc.

Now, if a coachee is the one intending to change, then what does a coach bring to this conversation? The coach is the change agent, the catalyst, the one who sees the coachee’s higher purpose and enters the transformative conversation only to accelerate change and maneuver the direction towards desired outcomes. It is not necessary that the coach has the expertise, background, or experience in the area of interest of the coachee or the situation at hand. The coach doesn’t bring domain expertise or content knowledge to the coaching session. A coach doesn’t give answers but asks the right questions for the coachee to delve deeper and find the answers within.

The basic concept of coaching revolves around conversation and asking questions. For lawyers, coaching can bring numerous fixes which they face in their professional life. The key questions circle around work-life balance, efficient working, progression in one’s career and choosing from the various opportunities in the legal field. The beauty of coaching lies in not answering a question or making a decision on behalf of someone, but in asking the right questions to the coachees to make a decision which fits best for them. Several times, coaches hold the hand of coachees and aid the process of introspection.

ADDRESSING MENTAL HEALTH CONCERNS

Most of us are aware that the legal field comes with its own share of pressure, deadlines and stress, which are often associated with anxiety, depression, mental health issues and day-to-day behavioral changes. For instance, the senior lawyers working in law firms are expected to generate revenue as per financial targets, which are often overwhelming. This adds up to their existing workload, thereby making the working condition more miserable with all the added stress. This gets worse for the young partners, who find the transition difficult, as they have been used to working under the guidance of their seniors, without worrying about business development and targets.

A coach dedicated to lawyers’ coaching understands the background and lifestyle of lawyers. They are able to identify the causes of deteriorating mental health and are trained to identify issues which a coachee may find hard to express. Coaches help them in thinking in the right direction, especially while taking a life-changing decisions, leaving a positive impact on their mental well-being.

ATTAINING WORK-LIFE SYNERGY

Another vital dilemma in a lawyer’s life is the aim to achieve a favorable work-life balance at a point in their lives. Diverse expectations to be met, within a given time range, may often have an overbearing impact on lawyers, resulting in a mental conflict between deadlines and work. This is a challenge that all lawyers face, regardless of where they work. Personal time takes a backseat because of the deadlines. To top it, work can be monotonous and uninteresting at times, which can lead to a loss of interest, a lack of commitment, carelessness, and missed deadlines.

For lawyers, work and career choices are often based on opting for or sacrificing quality time with family. There are also bi-polar phases of being workaholics to advocating for life-work synergy. A coach helps coachee in identifying their priorities and how to balance them during these transient phases. Coaching is also helpful in helping coachees realize what really matters to their deeper self and how to take decisions that are in alignment with their inner calling.

TAKING CRUCIAL DECISIONS

Whether it’s the burden to increase profitability or discussing a career goal to achieve something one has always dreamt of, a coach helps lawyers with crucial career decisions and guidance. They step in to mitigate the overwhelming effect and help a lawyer take decisions from peaceful and settled state of mind. This includes sessions where they help a lawyer in listing down ways to achieve the said goal or discussing pros and cons of a crucial decision with reference to future prospects. Through visualization and kinesthetic experience creation, coaches can help a lawyer in thinking from a third-person perspective and help them realize how different variables matter while making a choice.

Coaching helps lawyers across all age groups and professional streams towards development and implementation of business strategies, augmented productivity, improved leadership, teamwork, and relationship management skills. It also assists lawyers in identifying goals, breaking them down into bite-sized objectives to make them achievable and to avoid a general sense of overwhelm. As an effectively guided process, it triggers deep & structured changes to the thinking process, helping the lawyers overhaul the way they approach & organize work.

PANDEMIC, TECHNOLOGY & NEED FOR COACHING

Technology has transformed the world into a global village by binding people together in the times of social distancing. However, technology has also brought extreme changes in the way of working across all industry sectors. The Indian legal sector hasn’t been spared changes from the ‘new normal’ surrounding the increasing work from home and remote-working culture. Client expectations have risen dramatically as a result of the widespread use of technology to remain available and accessible round the clock. The access to internet, information and documents from anywhere in the world has put lawyers under a lot of pressure. Clients are increasingly expecting their lawyers to be proactive in deliverables. The long working hours have transformed into odd working hours and weekend working. The overbearing expectations from clients have further contributed to work-related stress in lawyers’ lives.

However, with the help of communication tools and techniques, coaches have been successful in handholding the lawyers in all realms of their lives – right from commercial-centric business decisions and leadership skill enhancement to more personal-oriented life issues and career choices. During the pandemic, a greater number of lawyers have resorted to appointing coaches to promote out-of-the-box thinking and to be able to look at the issues from a different perspective. Through constructive feedback and partnering with lawyers in their growth journey, coaches help them build confidence and create self-accountability towards goals.

FOCUSSING ON THE SILVER LINING

Coaching is an empowering exercise. One of the first principles any coach is familiarized with is that ‘people have real resources within’. A coach only activates the imagination, curiosity, and energy flows through which the solutions come to the surface. While every profession deals with its own set of challenges. It is important to be guided by someone who is aware of the functioning of the profession. Such a coach plays multiple roles of counsellor, therapist and a sounding board. But the most important role played by a coach, when it comes to lawyers, is that of an accountability partner. With the right mix of emotional and professional connection, they trigger the thought process and prove to be catalysts of finding solutions from within the coachees. They not only help in identifying the turbulence, but also help in resurfacing from it through a collaborative ‘experience building’.

During the course of this ‘experience building’, the lawyers are made to think about larger vision, values and evaluating a situation from diverse perspectives. They are guided into identifying factors in their internal and external ecosystem that are conducive to their goals. This exercise paves way for the identification of resources that were always available with the coachee. Coaches neither find new solutions, nor acquire new resources. They only create the shift of energy within the coachee – from emotion to energy in motion.

Integrating Strategic Planning and Strategy Execution

Nick Jarrett-Kerr

Professional service firms are typically littered with uncompleted strategic projects, failed initiatives and strategic plans that have remained in a drawer (or a computer file) almost as soon as written. It has often been observed that professionals are better at ideas and planning than in putting those plans into reality by means of effective implementation. To state the rather obvious, any yawning gap between strategic planning and its implementation is a mistake. The job is not done when the firm has produced a finely honed strategic document, beautifully printed and glossily bound – however wide and comprehensive has been the consultation process. The danger comes from a mindset that assumes that the plan is a lofty leadership endeavour and that implementation is low-level operational stuff that can and should be delegated.

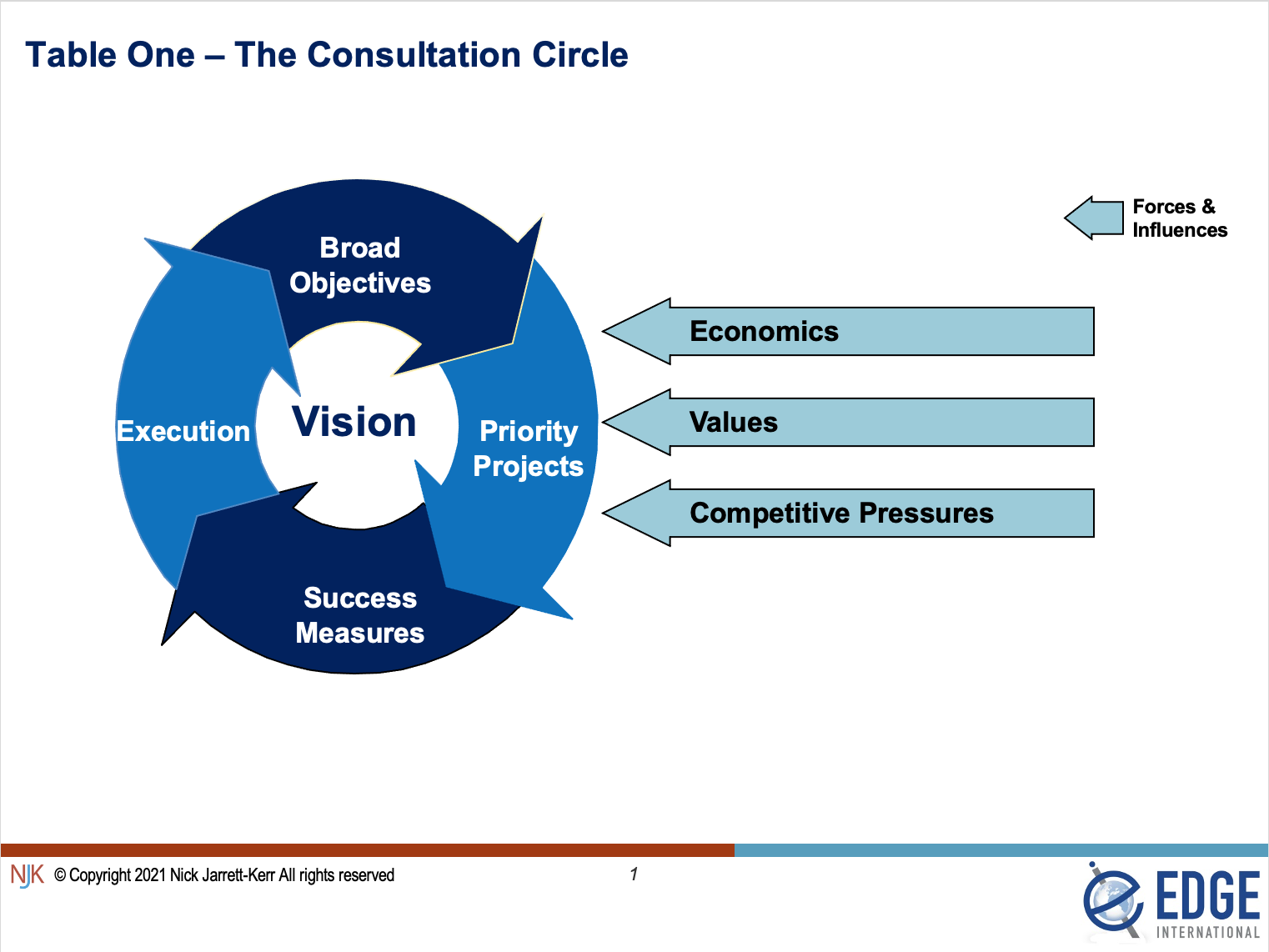

Strategic planning and strategy execution are best seen as an integrated and iterative process in which the broader and more visionary aspects are then cascaded down into action throughout the firm. In corporations, the leaders of the company for the most part craft the strategic choices involving larger long-term investments, and then tend to cascade the more concrete, day-to-day decisions down the hierarchical structure. Professional service firms (except the very large ones) tend to be smaller and less hierarchically layered than larger corporations but the same thinking applies to firms of all sizes; that the leaders should first agree and set out a broad path and vision which will hopefully stimulate the action that should follow lower down the organisation. The cascade imagery is helpful to a point but still has overtones of a hierarchical delegation. I prefer the imagery of a closed loop approach (such as illustrated in Table One) which stresses the collaborative aspects of strategic planning without which lawyers at the coal face will not take responsibility or ownership. It achieves this by facilitating an information consultation and feedback feature that enables plans to be checked and adjusted in the light of experience and outcomes. In this approach, rather like a ball being tossed and caught back and forth, or round and round, the purpose is to give all the participants in the process the opportunity, at each level, to help decide the implementation steps (and the accountability for these steps) to achieve each strategic priority project, and the accompanying success measures. This process of circling back is particularly important where there might be problems in capability or capacity (human or financial), and to establish what resources are be available and what commitments need to be made to address the execution of any plan that is agreed. All the time during this consultation phase, other forces and influences will arise to inform the discussions and processes – the firm’s financial health, the values the firm espouses and the competitive pressures that the firm faces being some of those.

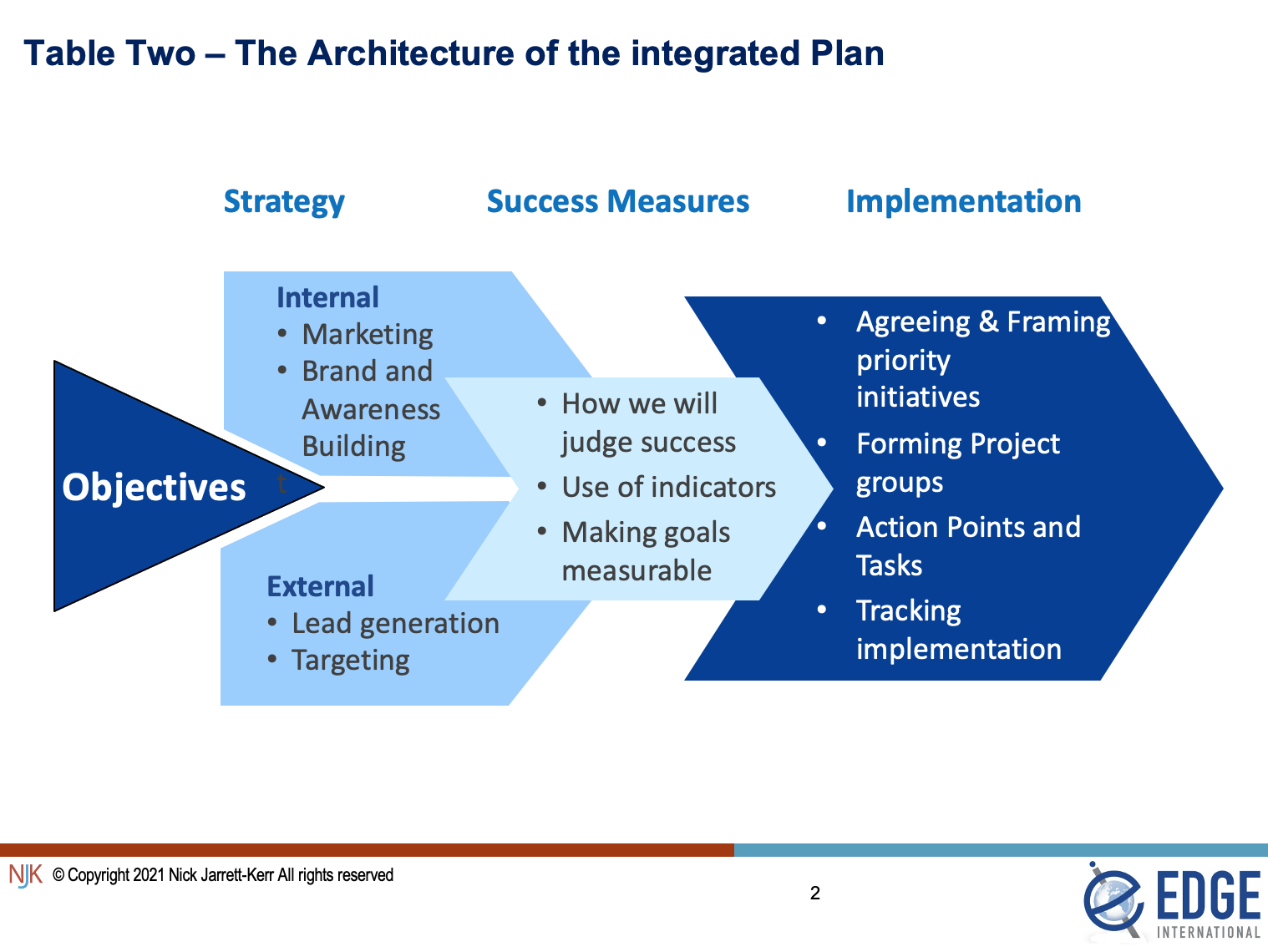

After this process has been concluded, it is then possible (as illustrated in Table Two) to design and build a truly integrated plan that links all the essential moving parts and introduces lines of accountability and feedback. At this stage the broad path can be fleshed out with more detailed projects, timelines and actions. The magnitude of the current challenges to the professional service sector cannot be understated. If Table One is seen as a spinning wheel, then it needs to spin ever more speedily.

Partners: Escape Velocity Begins Now!

Mike WhiteWell thankfully, it’s a new year! As you do all that you can to reach “escape velocity” and set the table for great things in Q3 and Q4, I caution my clients to make a psychological commitment to put things in motion now to create a rich set of opportunities later in the year.

I spend time with many of my clients during this time of year to encourage them to initiate many “January-February meetings.” My recommendation takes two steps: i) between now and the end of January, send out emails to suspects, prospects, or target-rich existing clients inviting them to join with you on a 20-30 minute call; and, ii) between February 1 and February 28 have your “January-February meetings” with those who responded to your invitation.

What are “January-February meetings?” January-February is a time of year when your CSuite contacts are: i) no longer hassled by year-end 2020 issues; ii) thinking about 2021 priorities that they can point to with specificity and clarity; iii) not yet consumed by this day/this week 2021 urgencies; iv) most open to engaging in high value “thought partnering” discussions with smart people like you; and, v) most forthcoming in sharing with you all of their gaps/exposures, as well as their hopes and dreams for the coming year.

Executing on this strategy requires you to have a sense of urgency. Many of you are managing a number of well qualified, well developed discussions with mature prospects. In other words, between handling your existing client work and advancing your mature opportunities, you have plenty to say grace over. However, I encourage you to resist the urge to blow off current efforts to set up your “January-February meetings.” You have an unusual luxury now to put leverage to work for you that will soon evaporate.

Leverage? What leverage? The leverage you can and should make use of now is the single email template you can send out (with minor recipient-specific tweaking) to get many people to consider your request for a “January-February meeting.” A single email form sent out to many recipients- now that is leverage! In business-speak we call this “doing something at scale.”

So, what does this “email” look like? Subject to recipient-specific customization, your email could look like the below:

“_________,

This time of year, I try to schedule time in January and February with select companies to learn more about what the year ahead is going to look like. Given what we do, I’m always particularly interested in the ‘experiments’ companies are planning to run beyond ‘keep the trains running’ and normal course priorities. At this time, businesses are coming out of their planning cycle and isolating areas, gaps, and opportunities deserving of unusual attention. While these discussions on occasion reveal to us ‘engageable’ subject matter, more typically our listening tour helps us learn unconventional insights about company types/sectors on which we focus. In short, it helps us be smarter about you, and other companies like you.

Push me out as far as you need to but if you’d be game to get together this month or next, I’d welcome the opportunity to set up a call or schedule a virtual coffee . . .”

Get going- now is the time to strike!

Talent Development: Beyond the Assignment

David CruickshankIn BigLaw firms, or in any firm with multiple associates, an assignment of work by a partner or senior associate, is a signifier of many things. To the management committee, it signifies leverage. To the partner, it is project management and the choice of competent associate. To the associate, it can signify repetitive drudgery or an opportunity to learn and impress. In the worst circumstances, with a tight deadline and insufficient support, it can signify a set-up to fail.

I propose a definition of the typical assignment that all members of a firm might embrace. An assignment is a career development opportunity.

Thinking of the assignment in this way, what can partners and associates do to ensure that there is a career development benefit for the associate in most assignments? (I’ll concede that every partner is going to have to assign some drudgery work that is beneath the development level of the available associate.)

Let’s begin with the initial delegation. As I teach in my management skill courses for partners and senior associates, a complete delegation must:

- provide a “big picture” context for the work

- review likely issues and resources known to the delegator

- be specific as to product, time allocation and deadline

- wrap up with a summary provided by the recipient.

While most of these steps are the delegator’s responsibility, associates can step up and offer a summary. This gives the opportunity to clarify and provide tips for the recipient.

To signify career development, a partner can do more at this stage. During the delegation, ask “Have you done one of these before?”. A “no” answer means that you’ll need to do some check-ins and coaching along the way. Each time, you’ll talk about how this work relates to more complex and challenging work that lies ahead for the associate. When you make the assignment, you can also schedule a time for feedback, even for the more experienced associate. This signifies that you care about both the work product and the associate’s development.

If you are going to be working with an associate for more than 40-50 hours in a year, you will be asked to evaluate their performance for the year. For that group of associates, the partner should keep a file of ongoing development notes for each associate. The assignment is core evidence of development, so you might organize your notes chronologically by assignment. Given the annual evaluation criteria, what strengths and weaknesses did the associate exhibit on this assignment? Share that feedback when the assignment is completed, not months later. Your notes are for a year-end evaluation summary.

In many firms, the partner-associate duo is not the only influence on assignment choices. Where a practice group has an assigning partner or committee, the partner cannot choose an overworked associate. However, that assigning body is also supposed to ensure that new assignments help build the associate’s career and that the work can justify the rate being charged to a client. While it is intimidating to do, associates who believe that neither of these goals is being regularly advanced, should raise their concerns with the assigning body. In a firm that touts its talent development (as most do in their recruitment pitches), the assigning body should be there for the associate.

Another institutional check on assignments is the diversity promise of law firms. Are diverse associates getting the same quality of assignments and career development as others? As partners keep assignment notes and prepare for annual evaluation throughout the year, they need to be conscious of even-handed treatment of diverse associates who are available for work. A diversity officer or committee can assist if you are unsure about how to handle this aspect of assignments.

Finally, when the assignment has been completed, the partner can “tie the bow” on an assignment by connecting it to career development, in a later conversation that covers four things:

- tell them how the work product was used in the overall transaction or litigation

- pass on any expressions of client satisfaction

- ask the associate what they learned from that assignment

- ask the associate what kind of future assignment would be a challenging addition to their career trajectory.

Assignments are not just about obtaining a work product. They are about developing and retaining talent.