Why Partner Integration Should Be On Your Agenda

Leon SacksPartner integration signifies that partners are working, both individually and as a group, in a manner that optimizes firm performance and is in consonance with their expectations.

Firm management is customarily occupied with monitoring the project pipeline, the productivity of professionals, client satisfaction, hiring the best professionals and winning and managing work. These are considered key contributors to a firm’s performance and success. However, partner integration can be an element of even greater significance to a firm’s performance and cannot be neglected or taken for granted.

Any sub-optimal performance at the partner level can have a multiple effect on the performance of the firm. This is because partners inevitably assume some management responsibility, whether managing a practice area, overseeing a group of professionals, handling certain client relationships or developing services and new business.

Partners consider themselves “owners” in the firm and, at a minimum, feel they should have some influence on how the firm is governed and managed. To the extent that is not achieved it can lead to dissatisfaction, a lack of motivation and even disruption, resulting in a significant, and often costly, distraction for firm management.

Do any of the following symptoms of a lack of integration sound familiar to you?

- complaints that a certain partner is not assuming his/her responsibilities or is not contributing sufficiently

- partners whose shortcomings (e.g. poor relationships with subordinates or lack of collaboration) are overlooked because they have good financials

- partners whose contributions are overlooked because their current financials are poor

- practice groups or business units operating autonomously and, perhaps, with distinct and even incompatible approaches

- lack of trust among partners reducing cooperation

- communication gaps between firm management and the partners at large, causing misunderstandings

- dissatisfaction with the fairness of the partner compensation system

- no effective performance evaluation process for partners (including feedback) leading to accommodations and misalignment

- partner promotion and advancement based on longevity rather than performance

- partner concerns as to lack of participation in decision-making

- controversial partner meetings without resolutions (disagreements allowed to fester)

Some of these situations may be overt (i.e. self-evident) while others may be covert (i.e. they exist but are not perceptible without specific questioning or analysis). All of them are examples of potential deficiencies in partner integration.

Where is your firm on the performance/integration map shown below?

Clearly performance and integration do not have unique definitions. They are a function of the values and objectives of a firm. Their measurement is dependent on an evaluation of a series of characteristics, many of which are qualitative rather than quantitative.

For example, performance may not be based purely on revenue growth or levels of profit but also on levels of client satisfaction, growth in certain service areas or practices and retention rates of professionals and/or clients. Similarly, integration may include evaluation of such elements as time spent on partner issues, level of partner satisfaction, client feedback, level of cross-selling and partner turnover.

Can you plot your firm’s position based on your interpretation of the level of performance and integration? Experiment doing this before reading on.

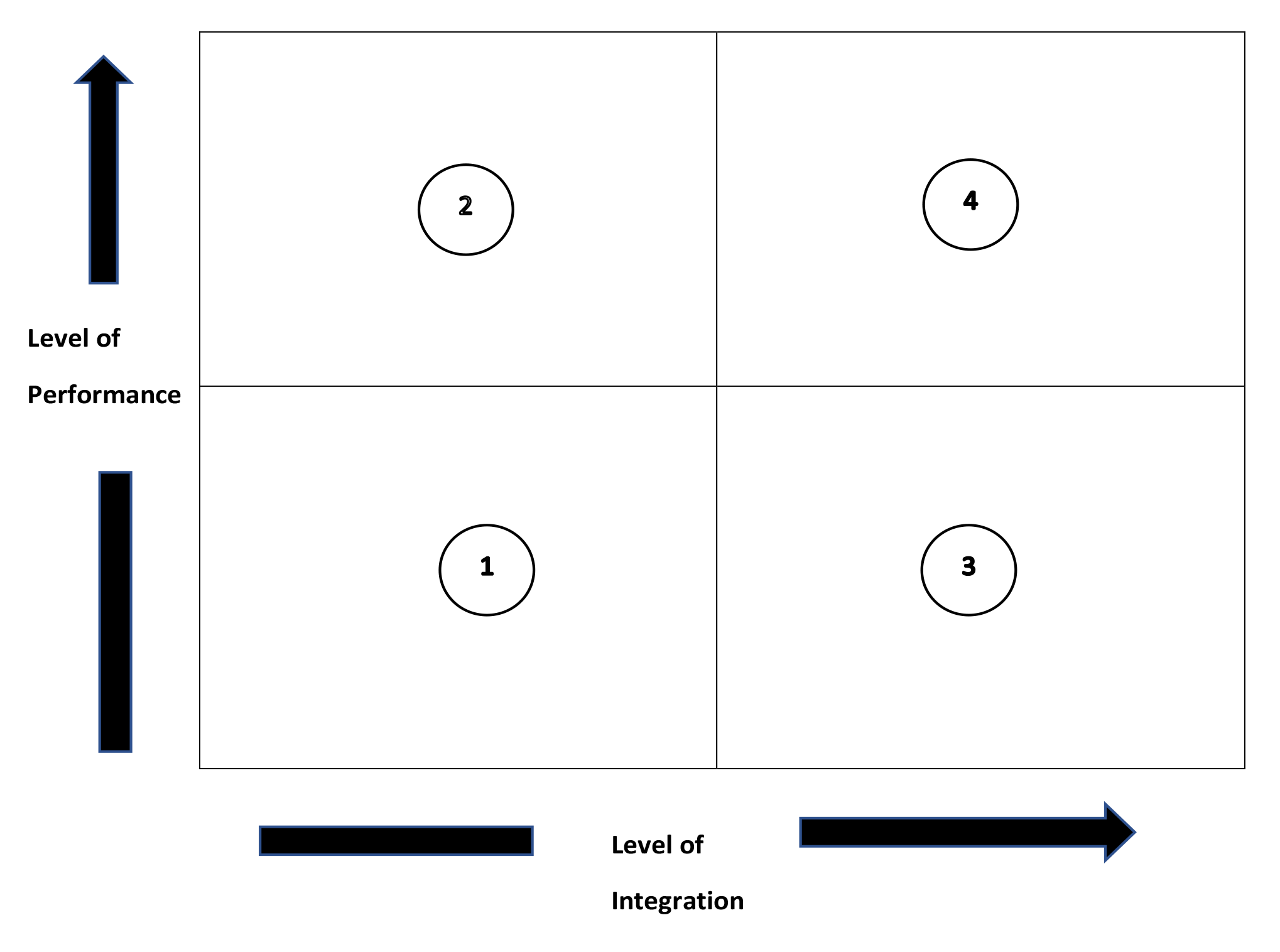

Let us now analyze the potential (common?) characteristics of firms in each quadrant of the map as indicated below.

Quadrant 1 LOWER PERFORMANCE/LOWER INTEGRATION

- Start-ups

- Group of disconnected partners

- Lack of management

- Unsuccessful merger (lack of trust/inability to change)

Risk: disruption, loss of partners/associates

Opportunity: improve financial returns, motivation and lifestyle

Quadrant 2 HIGHER PERFORMANCE/LOWER INTEGRATION

- Star individuals/practices run separately

- Group of autonomous units – perform well individually but focused on own P&L

- Lack of governance

Risk: loss of stars and/or practices

Opportunity: collaboration/synergies/cross-selling/joint client development

Quadrant 3 LOWER PERFORMANCE/HIGHER INTEGRATION

- Too nice – lots of “sticking together” but lack of drive/management discipline

- Tolerate non-performance

Risk: retention of performing partners, lack competitive advantage, lack of growth and retention of professionals

Opportunity: high growth opportunity and competitiveness

Quadrant 4 HIGHER PERFORMANCE/HIGHER INTEGRATION

- Uniform practices and strong financials across the board

- Smooth working relationships and stable governance structure

- Healthy interactions and high degree of trust

Risk: low risk of partner issues or defection

Opportunity: focus on growth and development and market leadership.

Clearly Quadrant 4 is the place to be by maximizing opportunities and minimizing risks. There is no perfect firm and there is no such thing as zero risk, but moving toward the top right corner of the map should be on any firm’s agenda.

That move would consist of making adjustments to the firm’s structure, policies and procedures, its mode of management and partner expectations. These may be included in a Partner Integration Program (“PIP”) that could then evolve into an on-going process as the subject matter is fluid and requires monitoring.

A PIP may address the following, amongst other needs:

- Promotion – promoting the right people facilitates integration and avoids costly mistakes. Promotion based only on the need to retain expertise and certain competencies may not be appropriate and alternative career paths are an option.

- Training and orientation – alignment to strategy, provision of skills to progress and motivation to grow

- Partner performance expectations, measurement and feedback

An effective partnership does not mean that all partners need to contribute in the same way but rather that the individual strengths of a diverse set of partners are used to maximize the strength of the partnership as a whole.

- Partner compensation – a system that recognizes the relative contributions of partners and is seen to be fair

- Adequate governance structure, leadership and communication channels

- Strong cultural glue

- Incentives for collaboration

A PIP will consist of the following phases:

- Define the components of partner integration to be measured

- Develop a plan to collect data and information for measurement

Remember that certain situations may be covert and therefore, to be complete, any diagnosis should include some form of consultation with the partners themselves (interviews, surveys, etc.). Such consultations should be conducted by persons independent of management so as to avoid conflicts and not constrain responses.

- Perform an evaluation of current status for each component

- Summarize findings and recommended actions for improvement

- Discussion and approval of action plan for implementation

Given that recommended actions will likely have a significant impact on partners’ roles and involvement with the firm, it is considered imperative that partners be consulted before any actions are approved.

I would be delighted to explore further the idea of implementing a Partner Integration Program, (PIP) should it be of interest to you.

Resolving Conflict: Trouble at the Top and Why it’s sometimes best to part company

Jonathan MiddleburghI have written previously (in an article in the Edge Communiqué entitled ‘Law Firm Armaggedon: How a major Law Firm nearly imploded and how the conflict was resolved’) about how the survival of law firms sometimes requires the capacity to resolve senior-level conflict. In that article I shared the story of one such conflict and how it was resolved through a long and difficult resolution process.

On that occasion conflict resolution achieved a truce between the key protagonists. In the situation described in this article the outcome was a recognition on the part of one of the key protagonists that it was best for everyone if he leave the firm. While ostensibly a less dramatic situation, in reality this outcome was important for the continued flourishing of the firm.

My Relevant Background

I described my relevant background in my earlier article.

I am an ex-barrister (I practised at the Bar in London for 12 years), schooled primarily in an adversarial approach to dispute resolution.

Around fifteen years ago, I started to retrain as a psychologist, completing my undergraduate equivalency in psychology while still practising at the Bar. After leaving the Bar, I continued my studies and started to practise as an occupational / organisational psychologist. Over the years I have worked extensively in the field of senior-level talent development in law firms and corporate legal departments, both in the UK where I live and also in the US and internationally.

As I explained in my earlier article, given the breadth of my background, I have been involved in a variety of projects, which defy easy categorisation. Several of these projects have involved senior-level conflict resolution, which has become a significant strand of my work.

A Case Study: Trouble at the Top

Unlike my earlier case study there was no cataclysmic precipitating incident that sparked my involvement with the law firm in question. Rather I was brought in ostensibly to help the Management Committee of the law firm to work together more effectively.

The background was that the law firm was a mid-sized regional firm in the UK. The firm had grown rapidly over the last 10 years, through a mixture of organic growth and as the result of a couple of large mergers.

The Managing Partner of the firm was half way through a second term of tenure, having been re-elected unanimously as Managing Partner prior to his second term. He had been at the firm for over 20 years and was coming towards the end of a very successful career as a transactional lawyer.

The other members of the Management Committee were the heads of the firm’s key departments – litigation, property, corporate / commercial, banking & finance and private client – together with the firm’s finance director / COO.

My introduction to the firm was via a consultancy that had been helping the firm with the development of a new 5 year strategy and the implementation of some key organisational and technological changes. The consultancy, in discussion with the firm’s HR Director, had identified that it might be helpful for someone to do some team development work with the firm’s Management Committee, as the Committee was not fully aligned on some key aspects of the proposed changes.

The HR Director felt that it would be helpful for the Management Committee to have a team charter and described this as the core of the necessary work when I first met with her. I was unconvinced that this was really at the heart of the necessary work, but decided to refrain from expressing this until I was clearer about what was actually going on.

What was clear from my initial briefing, however, was that all was not well at the top of this organisation. Although not presented as of key concern in this initial briefing, it was clear that there was a degree of conflict between members of the Management Committee. It was also clear to me that if the top team was unable to align it was highly unlikely that the planned changes would be fully effective.

Choice of Process

The HR Director was convinced that the implementation of a ‘team charter’ would help ameliorate behaviour of Management Committee members. I initially tried to question why a team charter would be a panacea but it was clear to me that the HR Director was focused on the team charter and did not want to listen to other possible approaches to the situation.

Rather than continue to debate this issue with the HR Director I decided that the best approach was to agree that I would work towards the Management Committee embracing a team charter. I suggested that I have a mix of conversations with the team members combined with a series of workshops dealing with issues emerging from the conversations. I suggested that I speak first to the Managing Partner and that I then have meetings with the other Management Committee members. I explained that I felt that the Management Committee members might welcome some coaching and support in relation to their respective roles in the change process, in addition to my providing support to the Management Committee as a team.

First round of meetings

I met first with the Managing Partner. He was very happy to engage with the process and acknowledged that the behaviour of the Management Committee was holding back the change process. It emerged from the discussion that the Managing Partner felt that the head of litigation was a particularly disruptive influence on the Management Committee. He was resistant to many of the proposed changes, in particular to some of the proposed changes in technology and to more centralised resourcing.

According to the Managing Partner the head of litigation was undermining some of the work of the Management Committee and the external consultants. He was apparently having ‘offline’ conversations with Management Committee members outside the formal Management Committee meetings, seeking to persuade them to hold out against some of the recommendations or to resile from changes that had already been discussed and agreed. The Managing Partner also suspected that he was ‘briefing’ against some of the proposed changes, i.e. telling his direct reports and possibly others that he was not in favour of the changes.

I tried to ask the Managing Partner whether he had called out this behaviour and, if not, why not – but it was clear to me that the Managing Partner was very uncomfortable discussing this and I was concerned that it would damage the relationship if I pushed him too hard on this.

The meetings that I held with the other Management Committee members confirmed that the head of litigation was a disruptive force on the Committee and highly resistant to the proposed changes. The other Committee members all mentioned that he tended to dominate Committee meetings and that his contributions used up a disproportionate amount of the available airtime. While it was clear that the Managing Partner was highly respected as a brilliant lawyer it was also clear that his leadership of the Management Committee was lacking and that he was, in the view of several of the other Committee members, highly averse to conflict and confrontation.

A couple of other factors emerged from these initial meetings. First, it was clear that although the larger of the firm’s mergers had taken place several years previously it remained highly significant in terms of actual and perceived loyalties of the Committee members. Several of the Committee members referenced the mergers and would refer to other members according to whether they were ‘original’ or ‘legacy’ i.e. whether they had been with the ‘original’ firm or one of the legacy firms with which the ‘original’ firm had merged.

It was clear to me that Committee members had retained their identities as either ‘original’ firm partners or ‘legacy’ firm partners and that those identities remained determinative of how partners were viewed by each other. There remained a web of alliance and commonality between the ‘original’ firm partners and a similar web of alliance and commonality between the ‘legacy’ firm partners. Each group was distrustful of the other group.

Second, it emerged that I needed to tread carefully in terms of my work with the Committee as a team. Several of the Committee members referenced a previous disastrous engagement with an external consultant who had done some work with the team, which had backfired badly. The consultant had held a kick off meeting without laying the groundwork by having individual meetings with the team members. In the kick off meeting the consultant had done an exercise with the team where he encouraged the team to imagine their fellow team members as common animals (badger, beaver, lion, tiger etc.) and to explain why they identified which particular colleague with which particular animal, based on that animal’s behaviours and attributes.

The exercise had derailed in a spectacular fashion. A couple of the team members chose to ‘zoomorphise’ their colleagues as animals which those colleagues regarded as, at best, inappropriate and, at worst, highly offensive. Everyone maintained a polite front during the meeting but there were post-meeting recriminations, the work with the consultant was abandoned, and the exercise had clearly scarred team relationships for a while. There was an understandable desire to avoid anything that might be a repeat of this disastrous experience.

I chose to meet the head of litigation towards the end of this first round of meetings. He was ostensibly extremely affable and keen to emphasise that he thought the team development work was an excellent idea and that he welcome personal coaching. However he was careful to extract several reassurances that our conversation was entirely confidential and spent a significant part of the conversation critiquing the proposed changes, emphasising the critical nature of his role to the success of the firm and explaining why, in his opinion, the litigation department was significantly different from the other departments such that his department should be excepted from several of the changes, particularly with regard to centralised resourcing.

I had been forewarned as to two of the head of litigation’s key traits – a tendency to interrupt while being asked questions and a propensity to keep on talking way beyond the scope of the question that had been asked.

The First Workshop

I decided to play it safe in the first workshop. I thought that it was important to build rapport with the team and to have a relatively gentle workshop rather than trying to tackle anything too ambitious.

I gave the Management Committee some general feedback from the conversations that I had held with them. I fed back with regard to the previous disastrous team development intervention and discussed with the team how that intervention had been counterproductive and caused considerable friction within the team rather than improving team relationships. I also spent some time discussing the fact that legacy relationships (i.e. relationships carried over from the ‘original’ firm and from the merger firms) still seemed to affect the dynamics of the group and there was general agreement as to this and how there was still a perception that some loyalty was owed to the legacy network of relationships.

We discussed in generic terms the key attributes of a high functioning team and the behaviours of such a team. These were captured for later use in the team charter exercise. While everyone expressed a commitment to operating as a high functioning team there was an acceptance that it would take time and effort to shift the embedded dynamics of the team.

My approach subsequent to the First Workshop

Following this first round of meetings and the first team workshop I reflected on the approach I should adopt moving forward.

I decided to focus on the following areas in the one to one coaching conversations:

- Legacy relationships – It was clear to me that the head of litigation was using the loyalty created by legacy relationships to undermine the work of the Management Committee as a whole. This was unfortunate as it seemed to me that the Management Committee – with the exception of the head of litigation – was broadly aligned around the importance of the proposed changes. So I decided, in my one to one coaching of the team members, to encourage them to focus on the importance of working together as one team and to seek out opportunities to work more collaboratively with those with whom they did not have legacy relationships. This could be as simple as having more regular catch ups with those individuals. I also encouraged the consultants driving the change process to ensure that the internal working groups driving the change were made up of a mix of players, so that the group members did not all share legacy relationships. It transpired that several of the key working groups had key members who had strong legacy relationships and these groups were gradually mixed up as a result of my recommendations.

- Offline conversations – Much of the work of the Management Committee was being undermined by offline conversations seeded or coordinated by the head of litigation. I decided to focus on steering the team members away from having these conversations, particularly conversations whose purpose was to undermine the proposed changes or to revisit decisions that had already been made by the Committee. I thought that it was unlikely that the head of litigation would change his approach to a more positive one – and, assuming this supposition was correct, I believed that it was important that the other team members deprive him of the oxygen he was being given to fuel resistance to the changes.

- Stronger leadership – I thought it was important that the Managing Partner showed stronger leadership, calling out bad behaviour on the part of the head of litigation. I was not sure whether he would be prepared to do so given his aversion to confrontation. I felt that I needed to encourage him to do so.

Subsequent developments

I had further rounds of coaching conversations with each of the team members, each round being followed by a team workshop. The bulk of each team workshop was consumed with the team discussing detailed aspects of the strategic change process (with me observing this work) and a small but significant portion of each workshop was devoted to discussing the team’s development.

I followed the approach outlined above with regard to the one to one coaching conversations, focusing on the areas outlined above in addition to providing each individual with support in relation to their roles in the larger change process.

A number of things happened as a result of the approach I adopted:

- Within a couple of coaching sessions the team members – with the exception of the head of litigation – increasingly realised and articulated in conversation that their interests were aligned to those of the firm as a whole rather than those of the legacy organisations. They became careful to consider whether their decision-making was based on loyalty or affiliation because of legacy relationships – and also to avoid intuitively conferring with legacy colleagues when making decisions. Several of the team members were surprised at the extent to which they had previously been influenced unconsciously or intuitively by legacy colleagues, and less so by their ‘newer’ colleagues (even though these ‘newer’ colleagues had been their colleagues for several years).

- The number of reported offline conversations declined, in particular conversations focused on reviewing or second-guessing decisions already made by the Management Committee. Specifically legacy colleagues of the head of litigation were careful to ensure that the head of litigation did not draw them into these conversations.

- Both legacy and non-legacy colleagues of the head of litigation became more likely respectfully to call out the head of litigation at their team meetings. Whereas the head of litigation had previously been allowed disproportionate airtime at these meetings, colleagues were more likely to ask him to make way for other contributions and to point out where he was being unjustifiably negative about aspects of the proposed changes.

It also important to note that the Managing Partner himself did not call out any of the head of litigation’s bad behaviour. When I raised this with him he attributed it to wanting the team to take ownership of the situation rather than imposing a solution himself – but I believed that the reality was that he was uncomfortable doing so, despite my efforts to encourage him to show clearer leadership.

In any event, within a couple of coaching sessions with the head of litigation it was clear that he was starting to feel marginalised as a result of the developments outlined above. He recognised that he was feeling increasingly isolated on the Management Committee and I encouraged him to explore with me why that was the case and what was going on. I was able to give him some of the feedback that the Managing Partner had not given him and to explain to him objectively and respectfully my observations as to his communication style. To my surprise he took some of these observations on board and realised, at least partly, that he was responsible for his own isolation.

Decision to part company

In subsequent conversations the head of litigation discussed with me whether he was capable of adapting his communication style – and whether he wanted to do so.

He recognised that aspects of his communication style were entrenched but felt that he could modulate aspects of his style if he wanted to do so. Indeed, he became notably more positive in a couple of team workshops and yielded the floor in those meetings to his more constructive colleagues to an extent that was noticed by the other Management Committee members.

Ultimately, though, he decided that he did not want to accept the new status quo. The new status quo would see (from his perspective) his leadership of his department sidelined in two key ways. He would have to agree that the technological changes would apply as much to his department as to other departments. He would also have to agree to more centralised resourcing, such that resources from the litigation team would be available to other departments depending on patterns of work flow.

For my part I encouraged him to think through the issues around his communication style – but as he edged towards the decision to leave his role I did not try to persuade him to stay. My view was that the team would work together much more effectively were he to leave.

I also helped him to think through the sort of environment that might play to his strengths. He decided (rightly in my view) that this would be an environment where he could call the shots. After exploring a variety of options he accepted an in house role heading a small team in a legal department that handled a heavy volume of litigation.

Outcome and Conclusions

As the work with the Management Team continued, the team charter itself receded in significance – as I had suspected it would from the start. We put together and agreed a team charter but in reality the charter captured many of the behaviours that the team had already started to exhibit. Those behaviours would not have developed without the coaching of team members and the team workshops.

As indicated above, the head of litigation parted company with the organisation to take up another role. This provided the opportunity to refresh the team and to bring in a new team member – the newly appointed head of litigation who possessed qualities of communication and collaboration lacking in his predecessor.

Following the departure of the head of litigation the team started to work together more effectively and became increasingly aligned with regard to the changes, most of which were implemented within a relatively short timeframe. The firm has continued to grow, pulling ahead of some of its direct competitors.

By way of footnote the Managing Partner himself moved on within a year of my concluding the work with the team and the ‘new’ head of litigation was voted as his successor. I can in no way claim any credit for this development – but the change in team dynamics enabled a new leader to step up and to replace a Managing Partner who himself had shown some clear deficiencies in his own leadership style.

For me, the core work illustrated that it is sometimes better to recognise that a key relationship (in this case the relationship of the head of litigation with his senior management colleagues) is not working – and therefore to part company – rather than to assume that every dysfunction can be resolved or that it is worth the time and expenditure of organisational resource to try to do so.

For further information or to discuss the issues in this article, please contact Jonathan Middleburgh at [email protected] or on +44(0)7973 836343

Edge Principal Jonathan Middleburgh consults on senior human capital issues and coaches senior legal talent in both law firms and legal departments. A former practicing lawyer who is also trained as an organisational psychologist, Jonathan has a wide range of experience helping law firms and legal departments to develop their senior legal talent so as to maximise business outcomes.

Virtual Coffee Breaks

Gerry RiskinReaching out to clients and colleagues while working remotely can seem awkward, especially if there is no apparent reason for doing so. The value of connecting during this time is in preserving and enhancing relationships by showing genuine care.

The most effective way to do a “virtual coffee break” is one person (be it client or colleague) at a time.

I suggest you consider these steps:

- Make a list of coffee candidates NOW before this idea slips away… put a few names down… if only two or three individuals come to mind, that’s fine — it’s enough to get started… add more as they occur to you. Candidates might include clients (past and present), referral sources, colleagues (who you may not be interacting with as much as usual because you/they are working from home), as well as any other individuals who are important to you professionally. Personal friends and family are important too but they go on a different list.

- Choose a person from your list. Don’t procrastinate – just do it!

- Text or email suggesting a 10-15-minute virtual coffee break.

- Your communication might be something like: “Matthew/Elizabeth, I hope you are well. It has been a while since we last spoke… I’d like to catch up over a virtual coffee if that sounds good to you. Would Wednesday at 3pm or Thursday at 11am work better for you? (Feel free to tell me if we need other options). Have a wonderful day.”

- Assuming an affirmative response, send a Zoom (or Microsoft Team) invitation.

- At the virtual coffee break, really have a beverage at hand (coffee, tea, water…).

- Ask how she/he is doing and be an attentive listener. Do not allow the conversation to deflect to yourself right away. Be gracious, but still persistent with caring and curiosity. Find out how your coffee break companion is REALLY doing. Also – an important note – be sure to use your judgement to not over-reach.

- After the call, make a note or two. You will be glad to remember details two months later when you circle back to check in again.

- Throw a reminder into your calendar to touch base again after what you consider to be a reasonable period of time.

This is so simple that you might just discount the idea and not do it. That would be a mistake.

Shoot me a note if you would like to set up a virtual coffee break with me — I can show you some strong anecdotal evidence as to why these “virtual coffee breaks” are so powerful.

The Art of Maintaining Client Relationships During Times of Crisis

Bithika AnandAs our inboxes experience a surge of emails and subtle marketing messages, we wonder whether many companies now see ‘being commercial’ as the new definition of ‘being professional’. Many of us are experiencing a sudden lack of work due to the current global pandemic; however, this presents an opportunity for us to genuinely connect with our clients and colleagues. As firm believers in nurturing relationships, we write this piece to share our views on connecting with others on more empathetic grounds amidst these testing times. If you’re curious about how some lawyers are still finding fresh mandates amidst the lockdowns and standstill of economic activity, read on.

A lot has changed globally over the past few weeks. We are witnessing unprecedented times and none of us was prepared to fight the global outbreak of this pandemic that has left several nations across the globe amidst a lock-down. Most of us are under a house-arrest and are now serving our clients from home. Thanks to technology, we have been connected like never before. A lot of organisations, as well as individuals, have explored totally new ways of working from home. That being said, things are not the same for everyone. A lot of our friends from the legal fraternity have witnessed a sharp decline in their work – firstly, because the courts have either suspended their operations or are only functioning specifically to cater to urgent matters; secondly, because economic activity is at an all-time low. A lot of us who have been yearning to have some free time to explore hobbies, now have a break from our otherwise hectic schedules and finally have down time. However, as time passes, many are now finding it difficult to find new ways to pass the time. Legal services providers, particularly, are finding it difficult to cope with this sudden ‘free time’ that has been bestowed upon them. Therefore, most of them are either finishing up their pending drafting work or are catching up on reading about things like evolving laws and upcoming industry sectors. Several others are interacting online more frequently than before with both clients and fellow members of the legal fraternity.

Empathize and Engage with your Clients

We have frequently been asked by colleagues from the legal field about what they should be doing during this time to ensure that they not only make productive use of this situation but also reach out to the fraternity on a larger scale. As firm believers in nurturing relationships, we give only one piece of advice to our lawyer friends: This is the perfect time to empathise with your clients and engage with them. This is an opportunity to go the extra mile for your clients and connect with them not only on commercial pursuits but also on a personal level. By doing so, you will gain even more of your clients’ trust and confidence. It is helpful in build long-lasting relationships to reach out to your clients in a selfless and serving manner. Have you picked up the phone and asked your clients how the outbreak of this pandemic has hit them commercially? Have you asked them how they plan to cope with the sudden lockdown of economic activity? Have you asked how you can help them build a contingency plan? If the answer to one or more of these questions is yes, you know the difference between ‘practicing law’ and ‘the business of practicing law’.

Extend a Helping Hand

We do understand that some of your clients may not be in a position to afford the fees of a lawyer at this time. Cost-cutting is the new normal and every penny saved does make a difference. But we do have a question: If you don’t reach out to your clients now when they likely need you most, why would you expect them to reach out to you when things go back to normal?

Some of us are making a big mistake by not extending a helping hand. If you’ve billed your clients in the past and have good professional ties with them (that have lasted for years in some cases!), then this is your time to pay back to those relations. Reach out to your clients and ask them what kind of help you can offer to them. Just like you, they may also be struggling with their contracts and agreements. Perhaps suggest reviewing any contracts or agreements that may be in question and offer to assist them in understanding those further. This is the time for you to offer to review their business plans and explain to them the legal aspects they need to bear in mind, while keeping in mind the sensitive business environment. This is also an opportune time to help them and their team members with online workshops/sessions on technical skill-development and legal knowledge enhancement.

Look Beyond Commercial Aspects

Endeavour to maintain a constant connection with your clients and check in on several developments as each day unfolds. As a service provider, one of your primary duties is to keep your client informed of the steps taken by legislature and judiciary, especially pertaining to areas of practice that may concern them. Take this time to study the upcoming laws that may affect your client’s businesses in the times to come and get yourself abreast with the latest legal developments. As business and law cannot be practised in isolation, utilise this free time to enhance your commercial acumen, especially related to the industry sectors to which your clients belong. At this time, when most businesses are contemplating a cost reduction to remain sustainable, legal fees should be the last thing that you should be discussing with clients. Of course, we do understand that at the end of the day we are all running a commercial venture and sustainability is as much an issue for you as it is for them. But that’s what differentiates a service provider from a trusted advisor. If you can help them sail through these challenging times, you can impress them, and most importantly build a relationship that will last for a lifetime.

Engaging with clients with the intent to resolve their issues and digging deeper to understand the practical challenges they may be facing right now is more impactful than sending them mere cut-copy-paste messages and business-promotion emails. Your communication at this point in time has to be strategic, well thought out and definitely not something that appears to be driven by commercial intent. If you need to go out of your way to make your clients feel welcomed at this point in time, please do so.

Gestures that Count

Are you wondering how some lawyers are still able to get new mandates and fresh instructions from their clients, even amidst this lockdown and general slack in the economic activity? It is because in order to build a successful practice, these lawyers are also working hard to build an ongoing relationship with each client. Such relationships survive long after the first agreement or mandate signed with a client. In these challenging times, and otherwise, never take your attorney-client relationship for granted. Even if you call your clients or engage with them just to say ‘hello’ and have a brief conversation with them, trust me they will feel valued. Small gestures like this will go a long way in building the perception of a dependable protector in the minds of your client. Such a client may not react well to a sales pitch, but they will at the very least be formulating a (likely positive) opinion of you. If you specialise in a particular practice area, try and explore participating in online/virtual events. This will show that you are reliable and assist in impressing your clients. Sharing passion and commitment for the work that you do will bring progressive changes to the field right now. This further strengthens clients’ perceptions on how much you care about the fraternity as a whole; and not just your individual legal practice.

Conclusion

It is hard to over-emphasize the value of building on relationships. Lawyers and law firms give a lot of thrust to business development. However, in that process, the relevance and importance of client retention can sometimes become somewhat diluted. It is also equally important, especially during the tough times all of us are witnessing today, that existing clients are valued and taken care of. What might today be a simple day-to-day consultation on simple issues could possibly in time evolve into open communications, matter updates, advice on business decisions and joint engagement in community-level activities with your clients. The silver lining to these troubled times is the opportunity they offer to grow new relationships and to be there for your current clients.

Ten Steps toward a Happier Firm

Nick Jarrett-Kerr I have been involved in the management of professional service firms for upwards of twenty-five years, and during that time much of my effort has been directed towards helping firms to develop and build what might loosely be described as “success” – strategic success, financial success, business development success, organisational success and positioning success (relative to rivals), as well as individual career and monetary successes for the professionals involved in the enterprise.

I have been involved in the management of professional service firms for upwards of twenty-five years, and during that time much of my effort has been directed towards helping firms to develop and build what might loosely be described as “success” – strategic success, financial success, business development success, organisational success and positioning success (relative to rivals), as well as individual career and monetary successes for the professionals involved in the enterprise.

Profit is of course key to the survival and prosperity of any business, and all the individuals in professional service firms are quite rightly focussed both on how to maximise the potential of the firm and how to achieve a sustainable, productive and effective organisation that adds value to clients and can appropriately reward its stakeholders. In this context, the topic of organisational culture, for instance, has concentrated on researching and analysing the dimensions of culture that have been found to make a difference in a firm’s success. The logic is that a powerful and positive culture can bring people together, serve as the glue that turns a bunch of individualists into a team, and fire up the firm’s members to perform better and more harmoniously.

Having said all that, I have not come across an enormous amount of discussion or analysis about what makes a firm happy per se – in other words what makes it a rich and harmonious place to work and hang out, regardless of the profit motive.

It might seem obvious that good leadership is a necessary element in any happy ship. Whilst in a crisis people respond to the imposition of martial law, a contented firm needs a more nuanced approach – a blend of determination and emotional intelligence. At the same time, nobody wants to be pampered for long or to live in an atmosphere where any sort of conduct is tolerated. Like parenthood, discipline with a lightish touch needs to balance out mere indulgence. Somebody told me quite recently that he thought that leadership and love overlapped a lot; certainly it helps enormously if the leadership group in the firm are passionate about the firm and what it does, and the leaders care deeply for the firm’s members.

In this article, I attempt to list ten steps that the leadership team can take towards a happier firm. They are based on facets of contented places to work that I have experienced or observed through the years. I am sure there are more! This does not set out to be an exhaustive academic piece but instead a set of reflections and suggested steps that lean entirely on my own experiences and observations.

Step One. Equipping for the Journey

The starting point for any journey is to know where you are going, how you are going to get there and the tools and kit needed for the journey. The objective of this step is that by investing in the office “ecology”, the office can become an awesome place to work.

Whenever I walk into the offices of a professional service firm, I am always struck by the atmosphere of the place, rather than the glossiness of the reception area. Some offices seem to radiate warmth and friendliness whilst others seem more clinical and lacking in energy.

There seem to me to be three features in which the happiest firms invest time and money. First, and most obviously, a well-trained set of reception and office staff clearly helps the visitor to the firm, so training members of the firm in soft as well as hard skills helps internally. Second, although a pleasant office may not be motivational, nevertheless an unpleasant place to work clearly demotivates. People may complain if a room is too cold but take it for granted and rarely enthuse when the temperature is just right. Hence, the obvious artifacts of office life need thought and care – the sort of attention demanded by enthusiasts of Feng Shui, for instance.

The third ecological element is the much vaunted, researched and analysed “organisational culture”, often described as “the way things are done round here”. I was once told by a managing partner of a law firm that he controlled the firm’s culture, but I think he was mistaken – the best anybody can do is to influence it (positively or negatively). A good way of doing this for for the firm’s leaders to be exemplars of the sort of positive cultural traits, values and behaviours that they espouse.This is a tricky area in which to invest – soft, long term, fuzzy and almost impossible to measure quantitatively.

Step Two. Stepping up Intercommunications

One of the most often heard complaints about an unhappy workplace relates to communication: specifically when it is poor, patchy, economic with the truth, or lacking transparency. There are some significant structural and emotional barriers to good communication in law firms. Teams, practice groups and offices can easily lapse into functional silos, with poor communications even between people on different floors in the same building. In addition, the concentration on maximising the billable hour and the drive to prioritise time generally, combine to reduce interaction between staff. The use (or misuse) of email, and stilted discussion at formal team meetings become a poor substitute for the easy interchange of ideas which can often take place in a semi-social setting. What is more, many firms have grown to the extent that fewer employees know each other. Whilst communication between friends is often difficult, communication between strangers can be fraught with problems.

The truth is that the traditional structure and hierarchies of professional firms do not lend themselves to a culture of easy communication. A ‘them and us’ tradition can lead to grapevines, rumour-mongering, suspicion, cynicism and muddled goals. In such an environment, many partners have difficulty in perceiving what their tasks and roles are, and how they are expected to contribute to decision-making.

The leadership team and the partners can also often find themselves singing from different song sheets and the fragmented results almost always have an adverse effect on morale. In response, there is a temptation to increase the number and length of meetings, memos, papers and e-mails, with less likelihood that the offerings will be read and understood. Conversely, some leaders continue to act on the premise that knowledge is power and purposely under-communicate within the firm so as to protect vital information and data from slipping out of their controlled grasp. Complaints about poor communication can also act as code for a general gripe about lack of involvement. What is clear is that much of the task for the leaders is painstaking, often process-driven, and at times downright boring. The clear message to firm leaders is that they should adopt a careful and methodical approach to their strategy for discussions, interchanges and information flows.

Step Three. The Long Walk to Collegiality

The assets of a “people” business tend to enter into and out of the office every day. Partnership relationships tend to be quite long term and although they are business relationships and not necessarily personal ones, they need investment. It is easier in this context to make a long list of the many mistakes made in firms in understanding and developing people. Closed doors, hierarchical thinking, displays of arrogance and self-importance, selfishness, impatience, intolerance of mistakes, eagerness to lay blame, morale-sapping behaviours, anger issues, bullying, sarcasm, disrespectful treatment of others, exploitation, unwillingness to listen, internal politics and jealousies are all features of unhappy firms where morale is low and where careers tend to be short-term. It is vital to realise here that the positive antonyms of the above list are formed by acts of will and matters of decision rather than by a feeling or a burst of emotions. Happy firms tend to be ones where the leaders and followers have made a conscious determination to invest in relationships, moderate their behaviours, and do their best for the collective membership and to individuals at all levels.

Step Four. Walking at Different Paces.

We tend to like people to be like ourselves. This can lead to intolerance of people who are different to us, and this can breed unhappiness. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn once observed that “it’s an universal law – intolerance is the first sign of an inadequate education”. The way in which the firm handles diversity is critical to the achievement of harmony – not just ethnic, cultural, religious or biological diversity, but diversity in views, opinions and behaviours. The key to the happy firm lies in understanding and making allowance for the very different ways in which people interact and behave as a result of their particular mixes of history, origins, upbringing, traditions and personalities.

Professional service firms are made up of many elements of diversity as well as different character types – extroverts, introverts, drivers, and thinkers are amongst them. People in firms tend to look at the world in different ways. Some constantly strive for results, some are laid back and amiable, some are analytical and some are process-oriented. People come across vastly differently as well – for instance, as dramatic, entertaining, sociable, closed, reserved, sensitive, submissive, or indecisive. None of these different approaches are necessarily right or wrong but there are at least two issues. First, relationships between diverse personalities can easily become toxic. Too often we fall into conflict and become critical when we expect everybody else to behave and interact just like us. The second issue is that strengths can become weaknesses; laid back people can become lazy, drivers can be dictatorial and perfectionists can become paralysed by their analysis. The disciplines of self-perception (and a desire to correct one’s own shortcomings) together with an attitude to others of understanding, appreciation and encouragement enable harmony to be achieved, strengths to be pooled, risks to be identified, and robust decisions to be agreed.

Step Five. Loving Curiosity

Conformity can have a somewhat deadening effect on the atmosphere of firms. All professional service firms need to have processes, systems, quality checks and compliance regimes. All of these are no doubt necessary for efficiency, risk management and regulatory control. However, I have often noticed how weighed down people often can feel because of the huge load of internal regulation, some of which can seem unnecessary. Morale suffers where there is too much unnecessary red tape. To quote Joseph Conrad, “The atmosphere of officialdom would kill anything that breathes the air of human endeavour, would extinguish hope and fear alike in the supremacy of paper and ink”. It is of course easier said than done to say that the compliance touch should be as light as possible, consistent with the firm’s overall objectives. Slavish and obstinate adherence to existing systems can however be avoided if firm members are encouraged (and rewarded) to be questioning, proactive and innovative in suggesting alternative approaches and new ways of doing things.

Step Six. Grinding Through the Pain Barriers

Happiness is not the absence of conflict. I have always loved the example of the grit in the oyster to illustrate the importance of constructive debate and the advantages of healthy argument on important issues. The tension between two valid points of view can often be tested and deployed to make decision-making better. Innovative ideas can be generated by the use of creative tension and energy. The problem is that in any discussion, bitterness, resentment and anger can easily set in and can be difficult to prevent when strong-minded personalities are involved. The key here is to engage with different points of view, and to tap into a spirit of healthy debate and commitment in order to find the best solution and to suspend personal stakes, ego trips and stubbornness. In meetings, this kind of engagement requires subtle and refined chairing skills. In individual instances of conflict that require intervention, diplomacy and mediation skills may be needed.

Step Seven. Engaging the Mavericks

The insistence on dogmatic convictions can lead to stagnation of ideas. Clients of professional firms appreciate the long years of experience that contribute to the skill bases of their advisers. It is of course good to rely on tried and trusted solutions to problems and challenges that are similar to ones that the firm has successfully encountered in the past. Pushed too far, however, reliance on existing approaches and solutions can lead to a stultified atmosphere where change is resisted at all costs, and new ideas suppressed or ignored.

In the last few years, some firms to their credit have recognised that innovation has traditionally been in short supply in professional firms. This is often because of the straight jacket of a billable hours’ philosophy that does not value time spent on exploring or creating new and different methodologies and emerging services. There is then a further question as to whether any mavericks at the firm are geniuses or jerks – many seem to have elements of both! I remember one partner who was extremely innovative and was constantly thinking up new ideas and plans, some good and some not. He was certainly not easy to get on with and, unless influenced by a moderating force, he tended to cause a lot of strife in the office. As always, there is a question of balance to be attained that cannot simply be defined by a recipe. Too much freedom and chaos (and unhappiness) results. Too much restriction of new ideas and stultification occurs.

Step Eight. Building Teamwork

Isolation breeds discontent. Law firms are one example of a professional services sector where some firms can be described as “motels for lawyers”, in which lawyers carry on a largely autonomous existence as sole practitioners held together by the glue of the compliance and professional regulatory regimes mentioned at Step 5. The same may be true to a greater or less extent of other professional service sectors. Such firms are not necessarily unhappy as such, but (apart from being in most cases commercially inefficient) can breed an atmosphere in which firm members are not encouraged or forced to build close ties with fellow members. Instead, people stick in their offices with their heads down and keep to their individual routines.

I have noticed that in such an environment people can often wear a mask or outer shell to hide their inner feelings of isolation, boredom and lack of career fulfilment. A culture can then easily grow in which everyone’s mask or shell condemns others to live the same pretence and keep their dissatisfaction a secret. There are of course many ways in which teamwork can be built – such as weekly team meetings, firm retreats, and frequent face-to-face interactions. In short, firms that I have experienced that try to be a “one-firm firm” seem (with some exceptions) to be more stimulating, contented and productive places to work than are “motels for sole practitioners”.

Step Nine. Looking up to See the Horizon

Corporate narcissism – where the firm constantly looks inwards and not outwards – is unhealthy and can imperil a firm’s state of well-being. I sometimes see firms where nothing seems to matter other than the firm itself. The firm lives in its own bubble and is both egotistical and egoistical – both feeling superior to others and preoccupied with itself. Clients become a tedious necessity, and the pursuit of unique or exclusive technical excellence is paramount. To some extent, these are excellent attributes if treated with moderation.

Nowadays of course firms are rightly required to embrace “corporate social responsibility” but often do so with a degree of hypocrisy or cynicism, to protect a sensitive client base or to assist in brand building. As a young lawyer, my then senior partner always encouraged us to give back something to the community by way of charitable work or towards a societal need. There are of course good business-building reasons for so doing – external involvements and networking are necessary to bring in clients and work. However, I have noticed that narcissistic firms seem to suffer a lack of oxygen and elements of claustrophobia that result from a refusal or inability to engage more than is absolutely necessary with the world outside.

The encouragement to look and act externally has three benefits of which the first is the business-development benefit of networking. The second is that relationships within the firm develop well where social and sporting activities are encouraged. Third is the point made by my former senior partner – not only is it right and proper to give back something to society, but selflessness frankly feels better than selfishness.

Step Ten. Achieving an Ethic to Work and Play Hard

“All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy,” or so the proverb goes. Some years ago, I recall asking a prospective lateral hire why he wanted to leave his firm and he replied that he regarded the firm as a “coal mine” in which the only things that mattered were chargeable hours and revenue generation. I am not sure that such a firm is ever a place of great joy and happiness, unless of course it entirely consists of workaholics.

The proverb does however have a second verse – “All play and no work makes Jack a mere toy”. Most professional service sectors – including the law and accountancy – are well paid and the expectations of hard work are accordingly and understandably very high. I would never argue for a pampering and indulgent environment where laziness is endemic and little effort is needed. I would however push for firms where – at every level – the taking of due and proper vacations is encouraged, and firm members are able to have a balanced social life and are not expected to endure an oppressive servitude.

There are good commercial reasons for seeking to make a firm a happy and rewarding place to work. After all there is a strong financial argument both that a contented firm is more productive and that the cost of people attrition can be measurably reduced by improvements in morale. There is however in my view a stronger case than commercial gain. My contention is that we all spend large proportions of our lives at work and that we owe it to ourselves and our firm that our career and the environment in which we work should be stimulating, satisfying and even fun. I would go further and suggest that the pursuit of happiness in our firms is more important than the pursuit of profit. None of the suggested steps is easy, and they all require long-term thinking, persistence and – above all – a willingness and passion to invest.

The New Direction of Law Firm Leadership

Ed WesemannThere is no law firm management topic about which more has been written than Leadership. The presumption at the base of most of these discussions is that the most successful professional service firms have the best leaders. And that prompts all sorts of further discussion about leadership styles, techniques, and the eternal debate as to whether leaders are born or bred – i.e., is leadership a function of natural personality traits, or can people be trained to be good leaders?

The legal profession has had an extraordinary run of success over the past 20 years. In terms of gross revenues, numbers of lawyers, and profitability, law firms are the poster children for success. Of course, we assume that if law firms are successful they must have good leaders, so we start looking at the traits that are present among law firm managing partners. And we are disappointed when we find little commonality.

I often think of law firm leaders as being like symphony conductors. Conductors are responsible for running the orchestra. They hire the musicians, select the music, decide the speed and volume of each section, and make sure everyone starts and stops at the same time. There is a local orchestra near here. They call themselves a “Democratic Orchestra” because they operate on what they call a “consensus” basis: new musicians audition for the orchestra as a whole; the music, and how it is played, is selected through consensus-building discussions; and the conductor is elected by popular vote for a one-season term of office. They are, by any standard, a terrible orchestra. But they survive because – being located in a low-population area – they effectively have no competition. Does this sound vaguely similar to many larger and mid-sized law firms?

When you ask most law firm leaders what their most important job is, they respond that it is building consensus. For many firms, this means that the leaders see which direction the consensus is headed and then get in front of it. It’s a bit like many politicians who look at the opinion polls to determine what their policy positions should be.

Unfortunately this consensus model of leadership – so successful for us in the past – seems to be breaking down. As firms grow larger and more international, leaders must deal with a range of educational backgrounds, languages, and cultures within their firms, and even multiple time zones. The result is that leaders find it extremely difficult to reasonably understand what people are thinking, little less gain consensus. And when larger international firms organize themselves in the loose confederations that are involved in Swiss Vereins, the process of developing consensus becomes almost impossible.

As the world changes for professional service firm leaders, they will find that they need a new set of skills. Firms functionally can’t operate with leaders who simply enunciate what is already popular and accepted by their partners. This translates into three demands of law firm leaders in the future:

- Leaders will have to be visionaries. That will require the creativity and intuition to be able to understand and plan for the future. The firms with the most accurate paths forward will win.

- Leaders are going to have to be great communicators. They will have to be storytellers who can not only communicate their vision but also personalize it in a way that makes it compelling for their partners.

- Finally, leaders will have to be builders. They will have to be able to implement by creating strategies to pursue their vision, and by building acceptance and alliances that permit their vision to be achieved.

In short, the easy money in the legal profession has been made. Becoming a successful leader simply by being in the right place at the right time will no longer work. Our future leaders will have to actually do what we have been crediting the leaders of successful firms with doing for the past 20 years.

In Successful Law Firms, Actions Speak Louder than Plans

Gerry Riskin“Doing” wins out over “Strategizing”

Studies predictably show that firms with a plan do better than firms without a plan.

As a managing partner, you need to determine whether your firm actually has a plan or not. Here is a test that will tell you if you do –

Choose a member of your firm at random and ask her/him what the firm plan is. If you get an answer that resembles the concept of your plan, you win. Winning would place you in rarefied air — most lawyers have no idea what their firm plan is (even the lawyers who were on the committee that drafted it).

The first step in implementing a plan is to communicate it, so that all stakeholders are on the same page. Once you have done that, you need to decide how you will execute it. Here are some suggestions that might help you get it right.

Be careful that what you plan passes the practicality test.

When senior partners lean back in their chairs to create a “plan,” they typically envelop each other in profound abstractions sifted through the filter of critical and analytical thought. The result is a work of art that is absolutely incomprehensible (except by those who created it) and therefore incapable of being executed. To make it worse, several senior people now have a stake in an unworkable plan.

Imagine yourself in a car that is being driven by several strong-minded individuals all at the same time, each with a different route and even a different destination in mind. Clearly, this is a pointless exercise. If you want to help your firm succeed, maintain a light touch on the steering wheel: give your senior leadership team a very short list of issues that are worthy of a place in your plan.

Decide how you will enlist the help of those who need to participate in the execution of the plan.

Have you ever tried to persuade someone to buy another brand of smart phone or automobile than the one they already own, or to change their minds on an issue relating to politics or religion? Okay. Good. Then you know how hard it is to change anyone’s mind about anything. People are deeply invested in their own opinions, biases and prejudices. In relation to firm planning, rather than arguing about the overall objectives, what you need to do is to show the lawyers whose help you need how the firm’s plan is going to help them to achieve their own objectives.

Encourage the firm’s lawyers to take small, incremental steps toward an objective with which they all agree.

As lawyers, we don’t normally think in incremental steps. We think in giant leaps. Ask a lawyer to write an article or make a speech and the typical lawyer will say that the only step involved is to “Write an article” or “Deliver a speech.” BZZZZT! Wrong! Writing an article or a speech begins with a single step – choosing a topic that is relevant to the audience. And how do you do that? By taking more, smaller steps: reviewing recent cases, perhaps, or observing recent trends in the industry you serve. After you decide on a topic, you move on to the next stage of writing your speech or article, and you break that down into small steps, too.

Your firm plan must be broken down into incremental steps as well, and appropriate constituencies within the firm must decide the baby steps that will be taken to achieve the objectives that affect them. By achieving one small step at a time, the team will gain a sense of accomplishment in moving toward an agreed-upon larger goal.

Create metrics to help you measure what you achieve.

If you know exactly what is supposed to happen next, you can determine whether it occurs or not: achievement of a step becomes a binary (yes/no) issue. Without metrics, you will pass George or Elizabeth in the hall and ask, “How’s the project going?” and you will invite meaningless replies such as, “Not too bad,” and “We are getting there.” Instead you need to be able to ask, “Has your team completed that list of top ten corporate targets?” – a question that requires a yes/no response. The clearer you are on what you expect to happen next, the greater the probability that your expectations will be met.

Firm leadership must over-communicate and then over-communicate again: You need to become obsessed with reporting back to the firm.

To return to our driving metaphor, imagine that the next time you take out your car, you find that the dashboard has been covered with masking tape. Will you take the car out in that condition – not knowing at what speed you are travelling, the oil pressure, the RPMs and engine temperature, or how much fuel remains and how much farther you can drive before the tank is empty? Not likely.

Keep in mind that your firm has absolutely no dashboard when it comes to the progress of the firm’s plan except what you communicate directly. You are the dashboard. Car dashboards update themselves in real time and are accessible continuously. A dashboard in an automobile cannot over-communicate. Neither can you.

The greatest minds with the greatest thoughts are crucial to the contemplation of complex legal matters, but thoughts will never move your firm closer to its designated objectives. Create a plan that your people can correlate with their own visions of success, and then design the path they need to take in order to achieve it. It is your responsibility to keep the display illuminated: show your people their progress along the way, thus offering them a sense of fulfillment as they advance together toward the agreed-upon destination.