Five Models for Assessing Partners and Lawyers

Most lawyers are reluctant to score, grade or rate their people. The perceived problem is that if you score low, it can result in an argument; if you mark high, it can make the rated individual complacent or arrogant. Most raters tend to play it safe and mark somewhere in the middle, thus making the entire scoring process rather pointless.

It is worth remembering again that we are seeking an evaluation system that concentrates on getting the best out of the individual in the future rather than just scoring the past.

There are many difficulties in a rating approach

- If lawyers are to be rated, they generally expect to see full details of the evidence presented and assessed – lack of trust usually means that a rating process can be long drawn out and complex if it based on factors other than financial performance

- Ratings tend to look at achievement of the measurable objectives or attainment of key performance targets rather than the value added to the firm by the lawyer’s contribution

- A rating system can assume that the value of a lawyer’s contribution to the firm’s performance increases because of a single year’s short term performance.

- Even with well defined, stretching and agreed objectives, there are many other factors which influence how successful a lawyer has been.

- Objectives can become quickly out of date and are often not well aligned to the firm’s standards and criteria

- The process of setting objectives is usually done very inconsistently, and criticisms of ‘soft targets’ abound.

- Ratings also work off individual performance, rather than contribution towards team performance

- Ratings tend to be heavily averaged – and as it has been frequently pointed out ‘averages are the enemies of the truth’. Raters are usually reluctant either to rate an excellent lawyer as excellent or to rate a poor lawyer as poor, and this leads to most partners being rated somewhere in the middle.

Any system of rating or scoring has to be not only fair but seen and trusted as fair – no easy feat. In part this is down to the credibility of the firm, its values and the credibility of the management team. In part it is also down to the assessment itself being properly and professionally conducted, and this can take up a huge amount of management time. Some firms insist, for instance, that any person who has the responsibility for completing a review, and for making remuneration recommendations, must explain how and how much he has mentored the individual in question over the period between appraisals.

Reliance on anecdote and title tattle must be avoided at all costs. At the other extreme, an over-legalistic approach should also be avoided. Additionally, the individual must have their say – there must be some element of self-assessment in the system. Whether or not each professional is required to produce a self-assessment memorandum or to address his/her performance in other ways will vary from firm to firm, but it is vital that everyone should be required to deal with the specifics of, amongst other things, performance against objectives.

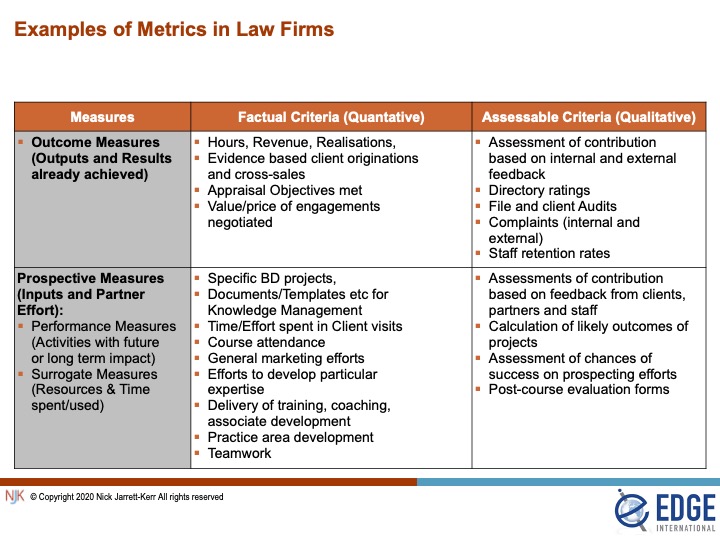

Data, evidence and measurement types

Most often, the data to be measured or assessed is quantitative (number of hours worked or revenue generated) but they can also be qualitative (achieving the grade ‘excellent’). Additionally, some of the measures will look at past achievements whilst some will be more prospective in nature.

Outcome measures therefore are used to describe results and accomplishments already achieved. Prospective measures describe two different types of metric. First, there are activities and projects which partners have undertaken but which have yet to show any success or return on the invested time. Second, there are surrogate measures. These fall broadly into two categories. The first category includes activities where the cost or the input can be measured (such as training expenses), but where no measurable outcome can yet (or sometimes ever) be quantified. The second category is where one measure acts as a proxy for another measure. For instance, a firm might seek to measure the level of recognition of the firm that exists externally with clients, non-clients, referrers and the local market; name recognition then can be used as a proxy for one or more elements of brand strength.

The table below sets out some examples of the types of measures which can be used and the annexe contains a more detailed list.

Rating and Scoring Models

It is important to note that we are talking about attaching importance to more than billing performance – we need to look across a broader spectrum. And for that, we recommend a ‘balanced scorecard’ approach in which lawyers are evaluated across a number of performance areas.

It is also important to embody the principle is that partners can choose the amount of effort they make in each critical area of performance, through their appraisal objectives, but they must make an effort in each category. Partners should not be allowed to pick and choose, and should attain at least a baseline competency across the board. If there are six performance areas, for instance, a partner must perform in each one and not be able to agree for the total assessment to be based only on three or four categories.

The overall assessment of performance will contain, of necessity, a subjective or qualitative element but equally partners are not being scrutinised on an individual basis – every partner’s contribution is analysed relative to all others.

The ultimate purpose is to place partners into categories or bands for rewards purposes depending on performance. However the assessment is carried out, it is clearly important to ensure that there is a gap between the performance of partners at the bottom of one band and those at the top of the next band down.

Even when a balanced scorecard approach is used, there are many models for an overall assessment. As seen earlier, there are many firms in which the profit sharing and compensation allocations are done very informally or even by annual negotiation. I have heard of one firm where each partner anonymously submits his rating of himself and his partners and the whole result is pooled. Where firms have achieved systematic assessment processes, they seem to fall into one of six main types which are described below.

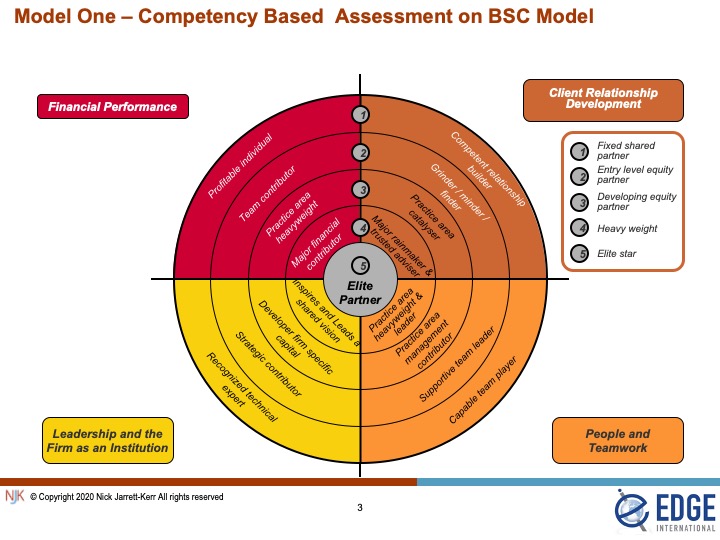

Model One – Competency Based Assessment on BSC Model

Under this approach, lawyers are rated in overall terms on a five point judgement scale against four to six typical areas of a Balanced Scorecard. – Model One below illustrates the four areas of financial performance, client development, people management and leadership. The scale shows a spectrum of competency expected of a partner from fixed share to elite partner but would be augmented and amplified by a more detailed competency framework

Competency based assessments concentrate on the individual skills and behaviours that are perceived to achieve high levels of performance and the value that the improvement of those skills should eventually bring to the firm. It can place too much emphasis on inputs at the expense of outcomes; there is a risk that partners who are good in theory but not in practice may do better out of such a system than they should. Equally, a competency based system, though extremely useful for development and training purposes and for partner appraisals, can sometimes become over-elaborate and bureaucratic if used for salary and compensation setting purposes.

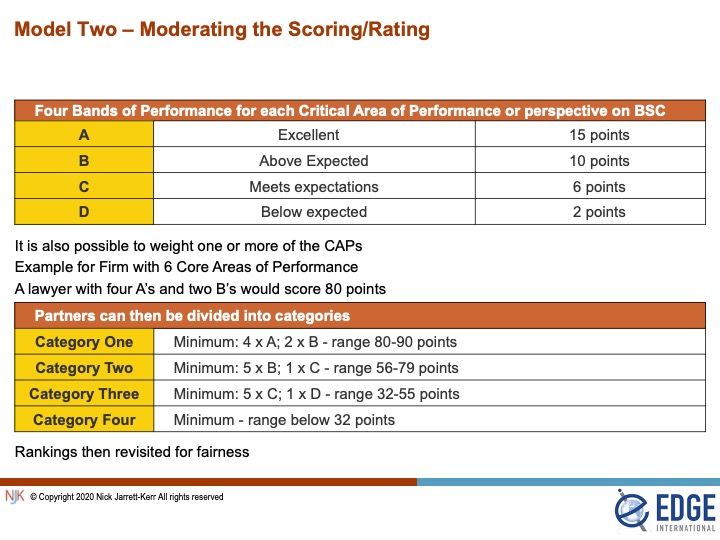

Model Two – Overall Rating and Scoring

Again four to eight grades of performance are used. Where five have been used, the following is a typical grading

A = Excellent

B = Above expected

C = Meets expected targets

D = Below expected

E = Intensive Care

Under this model, each of the six critical areas of performance would be scrutinised and scored, using the evidence and data referred to earlier in this paper. Whilst the attainment of personal objectives is clearly important and has to be taken into account, it is important for the scoring should be carried out against the firm’s agreed standards and criteria, and not just against the attainment of the partner’s personal objectives. The grades attained by each partner in each critical area of performance are then converted into an overall score which enables partners then to be banded according to their scores.

Some degree of subjective moderation then typically takes place to ensure that the bandings have achieved overall fairness, and there is often some intuitive forced ranking involved in setting both the bandings and the eventually allocated points.

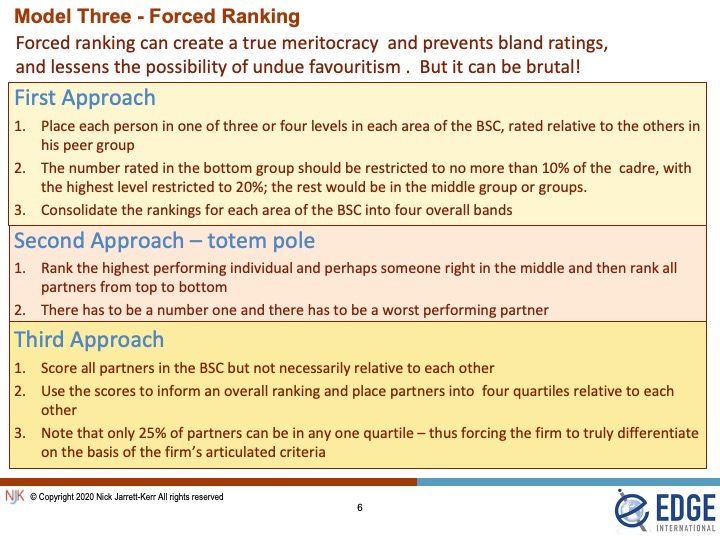

Model Three – Forced Ranking

Under a forced ranking approach, lawyers are placed in one of a number of levels in each of the critical areas of performance, relative to all other partners. One such approach follows a ‘bell curve’ methodology which will show a distribution of lawyers with a small percentage in the top category, a large percentage on the middle and a small percentage at the bottom. These percentages vary a bit from firm to firm. At some firms, the number of lawyers who can be ranked at the highest level is restricted to 20%, with 70% in the middle bracket and a bottom 10% of partners who are in intensive care and are in danger of expulsion.

In using a slightly different approach, known as the ‘totem pole’ approach, some firms take great care to identify and articulate the behaviours, performance measures and benchmarks actually achieved in that year by a partner considered to be right at the top of the firm (or sometimes in the middle of the cadre of well performing partners), so that all other partners can then be ranked consecutively from top to bottom.

A third approach – the quartile model – defines four equal quartiles into which partners are ranked. Again, this is a forced ranking approach as partners have to be ranked in one of the four quartiles and only 25% of the partners can be in any one of the quartiles. Put bluntly, the firm has to define the 25% of the partners who are the worst performers and who will therefore populate the bottom quartile.

A fourth approach is to adopt Model 3 and then to use the results of the scoring to inform a forced ranking by which the scores would be moderated to produce overall fairness

Which of these forced ranking methodologies is appropriate for the firm will depend on a number of factors including the firm’s culture. The argument in favour of forced ranking is that it creates a true meritocracy by differentiating partners on the basis of the articulated criteria required for success in the firm. It is however difficult – or at least invidious – to force rank any cohort of less than about ten people.

The further advantage of the forced ranking model is that it prevents raters from inflating their ratings and award superior ratings to all, or to give bland and middling ratings to the bulk of the partners. However, great care has to be taken with a forced ranking approach; recent research[1] has shown that forced ranking approaches can result in lower productivity, scepticism, reduced collaboration, damaged morale and mistrust in leadership.

Forced ranking also causes some problems for new partners, especially if performance-related elements are also linked with elements of seniority-based compensation. This is because newer partners, even if they fulfil or exceed all the objectives which may have been set for them, will often compare badly with more experienced partners in terms of overall contribution. Hence, a newly admitted equity partner at the bottom of a lockstep system may find as a double blow that his or her compensation is downgraded on the performance related aspects as well as the fixed elements of remuneration.

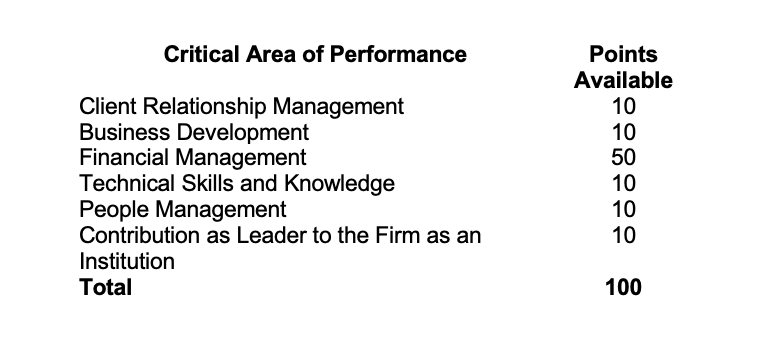

Model Four – Weighted Scoring

In some models, one or more performance areas can be weighted to give a higher weighting than for other areas. It is obvious that if four critical areas of performance are used, for example, they would each comprise 25% if no weighting is involved. If weighting is employed then generally firms avoid making any category higher than 30% to 40%. To give a weighting higher than this for any one category – in the view of some – tends disproportionately to reduce the importance of the other categories. Additionally, a high weighting on one category means that a lawyer could do well by focusing on only a few critical areas of performance, but if all are important then lawyers should at least perform to expectations in all of them. Having said that, we have seen many firms weighting financial performance to 50% or even 60% of the total score to reflect the importance of this area of performance

What is important is that any weighting must also reflect the overall objectives of the firm. If the firm’s imperative is for productivity improvement, then financial performance would be weighted. If business development is a key imperative, then it might well be fair to weight this factor higher than others. In the Edge International Global Partner Compensation Survey we asked firms to assess the relative importance of a number of factors when assessing partner performance and ultimately in arriving at partners’ remuneration. In the UK section of the survey, personal billing and revenue performance by each partner was felt to be very or extremely important by only one fifth of respondent firms, whilst business development and cross-selling achieved a massive 75% rating. Additionally, two-thirds of firms felt that Client Relationship Responsibilities had great importance. In other words, the contribution of partners in adding sustainable value to their firms by winning, cross-selling and retaining clients was considered as three or more times as important as the revenues which partners can personally deliver from their own desks.

The results were a little different in the rest of the world in that firms elsewhere seem to place a higher reliance on personal billings than the astonishingly low UK figure, and continued to regard personal billing performance as highly as other client facing activities. In the USA and Europe, for instance the value of personal legal work achieved a 90% rating (for high or extreme importance), with business development just a bit lower.

An example of weighting is as follows:

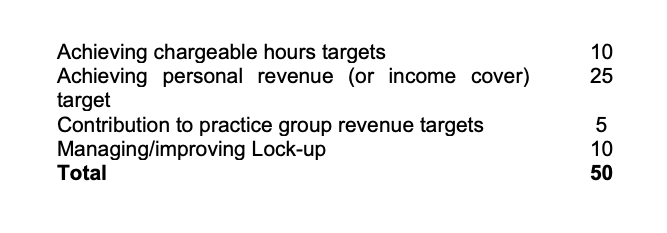

Within each area, the points can then be divided up still further. For example, Financial Management could be split as follows:

All the above are activities that can be monitored and measured. It is less easy with subjects such as Business Development where points may have to be attributed partly for efforts (inputs) and successes (measurable outcomes) – see the table (above) which shows examples of Metrics

By way of example, Business Development could also be split between activities such as contributions to successful pitches and client winning (measurable outcomes), networking activities (effort related input), cross-referrals (measurable outcomes) and involvement in Business Development Activities (effort related inputs).

Model Five – Overall Judgement

As far as I can be ascertain, the most popular method of assessing lawyers and allocating profit shares and compensation relies on a group of trusted individuals weighing up all the evidence and data and reaching some overall conclusions on the basis of the data which they have. The judgement is made holistically rather than atomistically. There are no fixed weighting or scores as the thrust of this approach is to produce a qualitative assessment not an entirely quantitative one. The model has often been described as a subjective model, the words objective (numbers based) and subjective (judgment based) being understood to differentiate between formulaic systems and those where a judgement is involved. Unfortunately, the word ‘subjective’ can also imply a flawed judgement that is influenced or biased by personal, conflicted or emotional factors. Hence I prefer to avoid describing this model as subjectively based and prefer to focus on the benefits of qualitative assessments as well as quantitative measurement.

Around half of the larger law firms set up a Remuneration or Compensation Committee for this purpose, whilst roughly the other half expect a high level Board to carry out the evaluation. For firms who do not wish to set up such a committee, other possibilities have included

- The firm setting up a ‘Partnership Council’ to decide such issues[2]

- Power to the Managing or Senior Partner to penalise or reward

- Decisions to be made by a group comprising the Department Heads

- Decisions to be made by all the Equity Partners

- Decisions to be left to outsiders, e.g., a firm of accountants

The role of judging committee should be fairly and consistently, and without favouritism or prejudice, to consider and evaluate the overall contribution of each partner. It or they should thoroughly examine all such data and materials supplied to it in relation to the balanced scorecard or critical areas of performance and any Key Performance Indicators. They would usually invite and consider representations made to it whether oral or written. They would take into proper account any lockstep arrangements and would also look at each partner’s personal business plan and appraisal objectives. Furthermore, they would usually consider the critical areas of performance and take into account the judges’ assessment of each partner’s performance and ability in those areas against the firm’s Key Performance Indicators. Perhaps most importantly of all, the judges have to consider or assess each partner’s overall contribution to the success of the firm.

Annexe – Metrics and Measurement

Client Relationship Management

- Number of complaints

- % of invoices disputed

- Number of initiatives completed from client surveys

- Number of visits made to key clients

- Client loyalty – Number of clients in top client list for five years

- Number of clients in key business sectors

- % of top client list in key sectors

- Share of wallet for key clients Client attrition statistics

- Key client hours growth/attrition

- Number of training events for clients per month/quarter/year

- Number of client secondments

- Number of cross-selling opportunities realised

- % of clients prepared to recommend or refer

- Client perception and/or satisfaction indicators and ratings (including letters of thanks etc)

Business Development

- New client wins

- Numbers of key client referrals/recommendations

- Engagements as % of total proposals

- Growth rates (numbers and/or revenue) in

- New clients

- Sectors

- Target client groups

- Origination statistics

- New matters statistics

- Marketing/referral cost per lead

- Number (or %) of leads generated by activities in

- online activities

- social media

- direct mail and newsletters

- seminars and in-house events

- articles written

- % of sales and BD trips resulting in an engagement

- % of time spent by on Marketing and BD activities

Financial Performance

- Fees per fee-earner

- Salary cover (revenue/salary)

- Average utilisation

- Realisation %

- Conversion rate

- Leakage %

- Lock-Up Days#

- Average realised rates

- % of revenue at premiums and/or discounted rates

- Contribution to Team profitability

Technical Skills and Knowledge

- Hours spent on technical training and research

- Number of post engagement debriefs (internal and/or with client)

- Client ratings on levels of competency

- Top legal skills

- Project management

- Business mind-set

- Team leadership

- Social skills

- Communication skills

- Negotiating skills

- Forensic skills

- Writing/drafting skills

- Ability to innovate and/or show initiative

- Trusted adviser status

- Directory ratings and rankings

- Specialist Technical skills acknowledged

- % use of electronic file management

- Average caseload

- Average speed to answer phone calls and/or emails

- Average time to archive completed files

- Average frequency of precedent/template updates

People Management & Teamwork

- Partner/Staff Feedback on

- Delegation and Supervision

- Planning and Time Management

- Training and Development

- Team-building

- Self-management

- Leadership

- Partner competencies and strengths

- Number of in-house training courses budgeted/planned for next month/quarter/year

- Training hours or ROI

- Number of instances of positive oral feedback every month

- Total hours spent in mentoring and appraisals

- % of appraisals carried out in time

- Absenteeism days

- Number of team meetings held or attended

Firm Leadership, Work Ethic and Firm Citizenship etc

- Attendance record

- Contributions to cross firm corporate/culture events/initiatives

- Number of internal quality control initiatives

- Rate of adherence to regulatory and internal compliance

- Average frequency of precedent/template updates

- Number of harassment, bullying and discrimination claims

- Number of social events

- Loyalty and length of service

- Number of Contributions to systems and processes

[1] Novations Group “Uncovering the Growing Disenchantment with Forced Ranking Performance Management Systems” White Paper (Boston, MA: Novations Group, August 2004)

[2] See my article “Governance in the Growing Partnership”