Creating and Rewarding Profitable Performance

The Links Between the Success of the Firm and Individual Partner Contribution and Reward

Published in: Kerma Partners Quarterly 2007, Issue 3.

This article is reprinted with kind permission from the original publishers. © 2007, Nick Jarrett-Kerr

The issues of partner performance and rewards are rising on law firm agendas. Law firm leaders talk a good game about how the firm ‘rewards what it values, and values what it rewards’ but in reality many firms have historically given scant regard to anything except seniority and billing.

The issues of partner performance and rewards are rising on law firm agendas. Law firm leaders talk a good game about how the firm ‘rewards what it values, and values what it rewards’ but in reality many firms have historically given scant regard to anything except seniority and billing.

This article focuses on the targets a firm should set for its partners if it wants to build profitably for its future and not just recognize past achievements.

Introduction

Methods of profit sharing in law firms have traditionally differed greatly as between North America and Europe. In Europe, the majority of UK law firms have historically operated against a background of ‘true partnership’ with equal sharing for all partners. In smaller law firms, the progression of an incoming partner towards equality tends to have proceeded by negotiation or as a result of senior partners ‘giving up’ partner of their profit sharing entitlement on an ad hoc basis. In larger European firms, the tendency has historically been for the firm to have a formal lockstep arrangement. In contrast, many North American firms have tended to operate on more meritocratic principles based on individual performance of partners as originating and working attorneys, which finds its most extreme model in the ‘eat what you kill’ principle.

What is interesting, however, is the extent to which we see a growing trend on both sides of the Atlantic towards performance related systems based on a wider managerial and business role for partners. There is now wide recognition that partners in successful law firms must develop their roles as managers of people, developers of business, leaders of teams, builders of ‘thought-ware’ and nurturers of client relationships. There is now wide recognition that partners in successful law firms must develop their roles as managers of people, developers of business, leaders of teams, builders of ‘thought-ware’ and nurturers of client relationships. This immediately raises a difficulty in that success in many dimensions of these roles can only be considered qualitatively rather than quantitatively. he identification of winners and losers (and those in between) therefore contains many subjective elements.

| The starting point for any initiative to change partner compensation system has to be the firm’s overall strategic goals |

…and a consideration of what the firm expects of its partners in terms of their leadership roles and individual performance. In addition, the objectives of partners (and therefore their resulting targets) must be deeply rooted in a firm’s values and culture. There is therefore a process of planned evolution in which the roles of partners can be developed at the same time as progressing the linking of partner targets to their ultimate compensation or profit share. This evolution should be based on five key underlying principles:

1) Recognising and understanding that there are a number of internal and external factors which influence and affect the way b which partners feel that their efforts should be rewarded and the partnership profit ‘cake’ divided.

a) Internally, experiences within the firm coupled with factors such as the firm’s size, its culture, values and accepted behaviours have a heavy influence on the reward system and vice versa.

b) The impact of external influences such as market consolidation and age discrimination legislation (in Europe) all affect the environment in which firms operate and the structures and disciplines which evolve within the firm as it faces up to its particular demands and challenges.

2) Breaking down the firm’s strategies to all levels of operation through the identification of the Key Areas of Performance (or ‘Balanced Scorecard’1) which will underpin both partner development in their role and the compensation discussions.

3) Defining the firm’s performance expectations for all of its partners at every level of seniority and development.

4) Regularly reviewing the individual partner’s progress and performance against the firm’s expectations; the system should be clear and simple. In the words of Jack Welch “it should be clear and simple, washed clean of time-consuming bureaucratic gobbledy-gook. If your evaluation system involves more than two pages of paperwork per person, something is wrong”2.

5) Determining the profit allocation should be based on partners’ contributions to the progress of the firm and not just the attainment of pre-ordained targets.

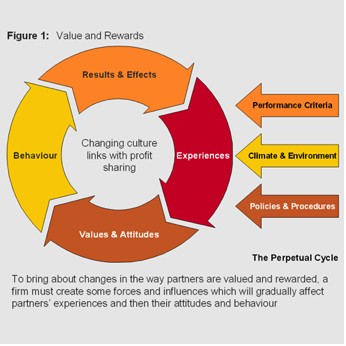

Values and Rewards: The Perpetual Cycle

Before a firm can link performance to profit it must consider its culture and whether a shift in values is required to adopt a different style of reward system. What do firms value? Most firms lie on a spectrum between the traditional collegiate firm which harnesses performance from its partners through a value system of trust and expectation of future higher rewards further up the lock step and the more entrepreneurial ‘eat-what-you-kill’ firm which harnesses performance by emphasizing internal competition for rewards based on yesterday’s performance. A firm’s culture and values will influence its choice of reward system and vice versa. The behaviour of partners is governed by their values and attitudes which in turn are based upon their previous experiences. To bring about changes in the way partners are valued and rewarded, we must create some forces and influences which will gradually affect partners’ experiences and then their attitudes and behaviour. For this, we need three things: (see Figure 1). First, a balanced scorecard approach encourages partners to believe that there are other things which the firm values as well as financial performance. Second, the firm must have in place the policies and procedures which will help to give partners the comfort they need to trust in the new arrangements. Third, the firm must work hard on the firm’s climate and environment to ensure that a supportive culture exists.

What is important is that a firm recognises that its values and reward system are interdependent and constantly evolving.

Driving For Excellence: The Firm’s Performance Expectations

In our view, every firm should define carefully the objectives which it has for introducing a performance management system for partner which can lead to the setting of goals and targets which can then be linked to profit sharing. The table on page 37 sets out some of the objectives which we recommend. After all, whether and how fast the firm succeeds at reaching its strategic objectives is determined by four factors:

- how much the lawyers work (volume),

- how effectively the lawyers work (value),

- how well the lawyers work together (level of collaboration),

- how hard work, value and collaboration combine to contribute to the success of the firm (contribution).

While the first criterium is clearly limited by the number of hours in the day, the latter three can be extended almost without limit. The firm needs to help each partner achieve absolute excellence in terms of their value and level of collaboration; to get there it will always need from every partner a substantial contribution on volume.

Having said this, no one wants to create “clones” or expects that every partner is excellent at everything. Instead the firm helps develop his/her strengths and makes sure that otherwise the partner is comfortably achieving the minimum requirements.

We have recently been working with a number of firms to define the expectations of their partners on a balanced scorecard basis. Our methodology requires in the first place a comprehensive study of the behaviours and accomplishments which are expected and valued of partners at every level in the firm. We have found that this then results in the establishment of criteria which are complementary not only to the firm’s assessment processes for promotion and rewards, but also to the firm’s overall strategy and objectives.

The Personal Contribution Plan

Working on client assignments is, of course, at the heart of any professional service firm’s purpose and reason for existence. At the same time, however, client work can become a comfort blanket for partners in the sense that it can provide an excuse to resist change and can be impediment to team-building and collaboration. The really successful partner has an ambition to be more than just a competent technician and client minder. We believe that widely used partner contribution plans (or partner business plans) can help in three ways. First, it helps a partner to be more ambitious and goal oriented. Evidence abounds that the more focused any professional becomes on attaining stretching objectives which he or she has personally set, the more likely it is that success will be attained. Second, if the individual plans harmonise with the team and firm plan, it can help bring about both a feeling of unity and a sense of common purpose and synergy. Third, if a partner is prepared to set and agree some meaningful objectives which can be monitored and measured, it provides a form of self-assessment which can be helpful in allocating compensation. The plan itself ought to be brief and needs to summarise the small number of critical business objectives which are relevant to the individual partner across the firm’s scorecard or key performance areas. It needs to be written in such a way that it will help the partner make decisions about priorities and time allocation, as well as clarifying how success in achieving objectives will be identified and measured. It further needs to set a compelling agenda for every partner to develop strengths, build skills and neutralise weaknesses.

Twenty Objectives For Partner Performance Management Processes

Strategic

1. Identify the areas where the firm must perform as a whole in order to achieve its strategic and economic objectives which can then be drilled down into ‘Key Areas of Performance’ on a balanced scorecard.

2. Ensure that remuneration levels match contributions to strategic objectives of the firm as well as the maintenance of cultural values.

3. Recognize/reward long term growth towards strategic objectives rather than just short term results.

4. Encourage partners to support new ventures and develop new services in line with objectives.

5. Encourage, motivate, value and reward high achievers who are critical to the firm’s strategic success and who contribute to an exceptional level.

6. Manage and develop performance in the broadest sense in all Key Areas of Performance.

Teamwork

7. Sustain concepts of teamwork between partners with greater collective responsibility for the performance of practice areas.

8. Encourage and reward the most capable partners to lead the firm and practice areas as effectively as possible.

Culture, Values

9. Reflect the values of the partnership and cohesion of the firm.

10. Value performance which contributes to the sustained growth of the firm and one firm approach.

11. Embrace a firm-wide approach to enable partners in different practice areas to be rewarded on a consistent basis.

12. Discourage maverick behaviour.

Human Capital Development

13. Clarify the differing roles of partners as working lawyers, producers, managers and owners.

14. Enable the firm to attract and retain partners of the highest calibre and introduce partners from other firms.

15. Be linked to internal training and review processes which support the development of partners’ development and improvement in performance.

16. Recognise that partners have different qualities and should be encouraged to focus on areas where they have strengths whilst contributing in all areas.

17. Link with the firm’s career development structures for its professionals.

Performance Expectations

18. Achieve clarity in the processes for reviewing/appraising partners and setting objectives.

19. Define the requirements and appropriate performance levels for partners at each stage of progression on the firm’s lockstep ladder or partner career structure both qualitatively and quantitatively.

20. Identify the data and evidence which will be collected and used to understand performance.

Reviewing Partner Development

At least every twelve months every partner should conduct a meaningful review of their

performance together with either their department head or the managing partner, as appropriate. The primary purpose is to discuss and clarify partner development and to set some helpful objectives.

The basis of the discussion should be first assisted by a preparatory self-assessment by the partner based on his personal contribution plan. There should be a summary by the partner of his chargeable work as well as major activities on non-billable work (both pre-agreed and own initiative), including any client or internal leader feedback. There should also be a 360°-reviewwith views from fellow partners, associates and staff, and, to the extent available, from clients. These types of review have been frequently placed by law firms in the ‘too difficult’ pile, but we have recently helped a number of firms produce state-of-the-art working 360° models.

The periodic partner review should lead to determining the areas of focus for improving performance in the next six to twelve months and for identifying the support the partnership can provide. The partner will then integrate this into his/her personal contribution plan that he/she will develop for himself/herself and discuss with his/her Department Head.

Problems With Setting Objectives

- The objectives are hurriedly drafted and skimped – they do not adequately reflect appropriate career development.

- The objectives are too vague and aspirational –they cannot be interpreted, acted on as a series of tasks, or measures.

- The targets are unrealistically high or too low – either will demotivate the partner.

- The process has become bureaucratic – it is seen as a paper chasing exercise.

- The objectives have no meaning and are left to gather dust – the appraised partner will wonder if the review process has been worthwhile.

- The objectives are simply imposed by the appraising partner and not ‘owned’ by the appraised partner – the appraisee will view their involvement as insignificant.

Setting Targets and Objectives

In many years of appraising and moderating appraisals, we have found that the most difficult and badly done section of the annual appraisals is the setting of objectives. One problem is that this is an area which is normally left until last on the appraisal form and is dealt with when both parties have become tired or when time has run out.

There are seven rules to setting targets and objectives:

- The most important rule is to ensure that the targets and objectives are linked to the overall strategy of the firm.

- Where you can, try to focus on outcomes rather than activities. This is much easier said than done. For example, instead of “work to improve cash collection”, one might say “by the end of the next quarter negotiate interim billing arrangements with the following clients”. Instead of “assist with precedent building”, one might say “review and redraft the firm’s standard lease for small offices by October 31st”.

- Make sure the wording is SMART and carefully worded.

- Check that the objectives are prioritised (use words like ‘must’, ‘should’ and ‘could’ to give a sense of this).

- Make sure that it is clear how the targets and objectives are going to be measured. Some metrics are obvious. Others are elusive, particularly when they are less specific and more aspirational. The key to this is to keep asking the question ‘how will we know when we have achieved success?’ The aim is to be able to set some measures based on one off our yardsticks — time/speed, cost, expected quality level, or positive results.

- Make sure that you agree some mechanism or timetable for regular monitoring.

- Finally, make sure that the targets and objectives are mutually agreed.

Conclusion

As clients demand more of their service providers and as the business world becomes steadily more complex, only limited success can be attained by individual lawyers working in loose association with each other and concentrating their efforts and rewards on solo endeavours. The case for investing in partner personal development towards a more collaborative business model is therefore unanswerable, both in personal terms (managing an individual’s own career), and in organisational terms (developing and managing for profitability). The development of a collaborative framework for partners has therefore to be consistently focused on two main aims — helping the individual to make the best of his/her abilities and helping the firm to make the most effective use of its people. A good starting point for any firm is to ask itself the following questions:

- Have we developed a clear vision of what has to change in our firm and why?

- What outcome-based goals would indicate success for the firm?

- What should be our expectations of our partners in terms of behaviours and roles?

- What are the skills and competencies which are most critical to our success?

- What feedback are we getting from our clients which will help us to improve and develop?

- What level of collaboration and teamwork do they expect?

- What are the issues and working relationships which must be mastered in order to drive performance?