Partner Roles and Responsibilities

This posting sets out to introduce some suggested methodologies for a firm to follow in order first to clarify what the firm expects of its partners and then to define what roles and responsibilities it needs them to perform. Partners equally need to be clear how they are to discharge their various roles as owners, managers and producers. Law firms have at last accepted the importance of developing management and leadership skills in their partners. This recognition is somewhat patchy and inconsistent and there is often a mismatch between what law firms say they value in their partners (in terms of the competencies and characteristics) and what they actually reward (often by recognising and rewarding billing efforts mainly or exclusively). Additionally, there is a reluctant but growing appreciation that skills and competencies can be developed across the management /leadership spectrum, from a base level through an intermediate level to an advanced state of leadership.

There is an initial point of confusion which lawyers make when considering management and leadership skills. The tendency of many law firms is to confuse management skills with the context in which those skills operate. Law firms tend to look at the different areas of management in their firm and define their expectations in terms of the behaviours, indicators, goals and outcomes which they would expect to see in those critically important areas of performance. Thus, firms may talk about people management skills, or business development skills. In truth, ‘People Development’ or ‘Business Development’ do not form specific skills in themselves, but comprise situations or contexts within which certain skills are needed. The underlying skills and characteristics to meet the firm’s outcomes and goals in the key areas of performance then tend to become rather vague and undefined. This makes it all the more important for the individual partner to gain a deep understanding of those attributes which he or she needs to develop in order to attain the firm’s objectives.

At the risk of stating the obvious, we are witnessing right across the globe a trend towards firms that attempt to be well-coordinated rather than just loose groups of individuals. Partners in more firms are beginning to work more closely in teams. We are seeing the development of a one-firm approach where consistently applied and agreed methodologies and processes are brought to bear upon clients’ matters. To some extent these trends are client driven. Clients want to see firms deliver a consistent and not a patchy service. All too often clients complain that the quality of service and indeed the style of service can vary enormously from partner to partner, from practice area to practice area, and from office to office. We have even seen clients complain that the style of documents (including fonts, prefixes, numbering and file names) differ in some firms between departments and from office to office; clients are not impressed. The imperative therefore is for firms to be run as businesses with well-designed systems and processes. Firms need to find ways of streamlining their services wherever possible. Clients do not usually want to pay for the wheel to be reinvented. They prefer to see the experience of the firm, garnered from previous similar engagements, put to use in their matter in a cost effective manner.

In order to achieve consistency of service and for the firm to be run as a business we are seeing firms embracing sounder management practices than ever before. This means four things. In the first place any partnership must take time to agree management roles, to select the right people and then to allow those people to get on with the job of managing. In the second place partners need to understand that they cannot be involved in every decision. This leads to the third point that partners do have to be supportive of their management and should avoid wherever they can opposing and undermining decision making. This does not mean blind acceptance – partners must be willing to take on responsibility and to cooperate which is slightly different from blind acceptance. They have to be accountable for their actions and decisions and ultimately they have to be responsible for their own autonomy in areas where they have to maintain independence. At the same time partners need to have an ambition to develop leadership skills and should be willing to work with those where leading. In other words, backbench partners, if I may call them that, should act as colleagues and companions but not as sheep.

Significant time input is required across the world for partners in all law firms. On top of time spent on client work, we are seeing partners being budgeted to spend marketing and business development time in the range of 300 to 500 hours a year and other non‑chargeable time depending on factors such as the size of team and type of client. Nonchargeable efforts also need to be made on client relationship management, team and human capital management and the partner’s contribution to the firm as an institution. This results in many firms expecting partners to spend (and record) a minimum of 2300 total hours per annum on the business of the partnership. Within this timeframe it should be possible for the non‑chargeable activities to be carried out even within the context of a large client portfolio.

In general, as the firm continues to grow, partners will need steadily to become managers of others as their main activity; they will need to reduce the time spent on files and matters, and to increase aspects such as delegation and supervision. In addition they will need to build capability and competence in four or five key areas.

1. Understanding the ‘Critical Areas of Performance’ in which partners need to contribute

There are six typical ‘Critical Areas of Performance’ which we often see in law firms. These are:

- Financial and Business Performanceincluding the manner in which each partner discharges his or her responsibility for managing the business and financial aspects of the Team/Department/Division for which he or she is responsible –

- Achieving superior financial performance;

- Maintaining good financial disciplines;

- Working hard and demonstrating long term engagement and commitment.

People Management, Leadership and Team/Skills Development

- Setting the right leadership example both to his or her own department and to other members of the firm by –

- Achieving cooperation from team members out of respect rather than fear;

- Setting the right example throughout the firm in term of work ethic, personal conduct and crisis management.

- Developing the profile of the firm’s people, their skills, abilities and strengths/weaknesses in depth and skills.

- Understanding the necessity of getting things done through others.

- Constantly working at communicating, delegating, negotiating, resolving conflict, persuading, using/responding to authority/power.

- Understanding the obligation to use power appropriately and the danger of the inappropriate use of power.

- Harnessing the power of the firm by creating, organising and energising powerful teams including the extent to which individuals within teams are encouraged to push the boundaries of their own team roles.

- Developing and assisting people by coaching, mentoring, counselling and developing them in any of the following disciplines – law, marketing, sales, finances, career, work-life balance and networking.

Business Development

- Contributions in general to build for the firm’s future by targeting better clients and better work.

- Achieving sustained value by originating (or playing a key part in originating) clients of the firm.

- Developing the firm’s client base to become and remain highly competitive.

- Cross-selling and introducing clients and referrers to others in the firm.

- Building marketing visions and strategies which are long-term, compelling and market-focused.

- Building the firm’s brand, reputation and profile.

- Performing an ambassadorial role to assist in the building of networks and profile.

Client Relationship Management

- Nurturing our client base.

- Fulfilling the on-going requirement to deliver excellent service to clients in the context of their particular needs.

- Working to produce new solutions which create value to the clients.

- Consistently providing streamlined cost-effective services.

- Effectively building, developing and maintaining strong client relationships.

- Contribution to the Firm as an Institution, Knowledge Management and Solutions including –

- Taking responsibility in an effective manner for the management of the firm, its various management functions (eg marketing, IT, compliance), its departments and its sub-groups.

- Contributing creatively to the strategic planning of the firm and its implementation.

- Contributing to the building of the firm’s Intellectual Property including precedents, templates, case management and workflows.

- Assisting in the development of leading edge Knowledge Management and high level technical know-how

- Demonstrating though his actions and the actions of the team compliance with the firm’s policies and procedures including regulatory compliance and good practice in relation to the firm’s own policies on disbursements, bad debts and client care.

- Actively helping build the firm’s processes and systems which contribute to the firm’s ability to grow its business including quality control/improvement, governance and management structure.

- Contributing to the development of a homogeneous culture and esprit de corps.

- Demonstrating the visions and values of the firm by example rather than in words alone.

Self-Development and Self-Leadership

- Evidencing continued development and commitment to developing competence and skills and challenging oneself to expand personal comfort zones.

- Acquiring new expertise and skills valuable to the firm.

- As a role model, demonstrating confidence and self belief, consistently acting with integrity and naturally trusted by others.

- Providing an example of being self-initiating, self starting, self learning, committed and engaged.

- Displaying the ability to pursue goals with a deep sense of purpose and direction.

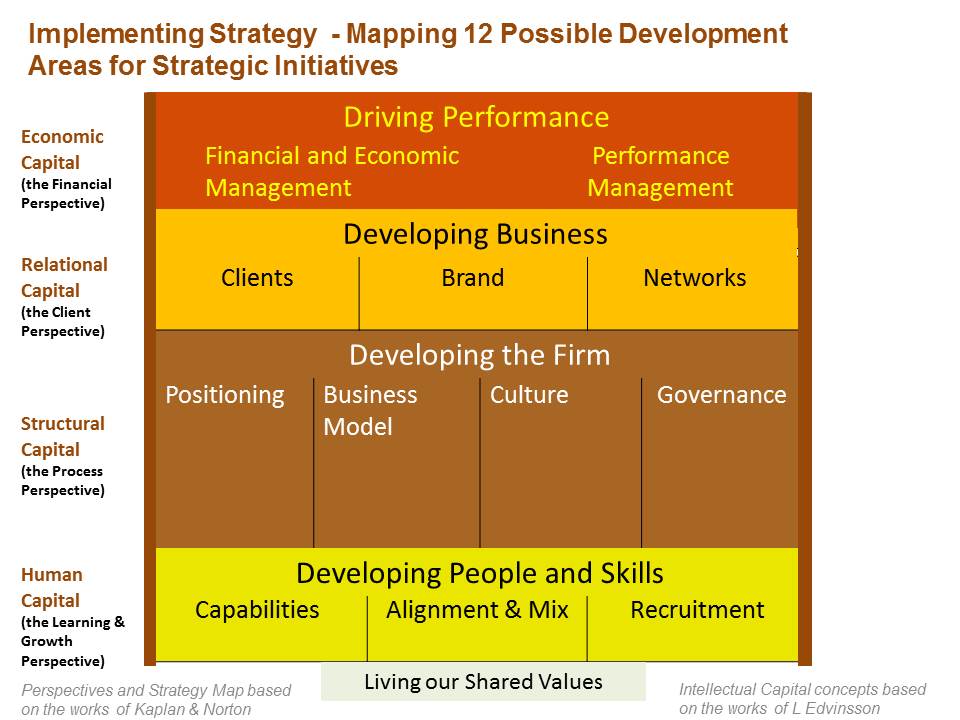

These six areas correspond roughly both with the concepts of Intellectual Capital which I have covered in other articles and The Balanced Scorecard (suggested by Balanced Scorecard authors Kaplan and Norton)[1]. The Balanced Scorecard is a methodology to align an organisation’s every day operations to its long-term strategy. Its purpose is to translate vision and strategy into all the actions that the organisation undertakes. This is done by looking at desired results from certain perspectives. For law firms, I have suggested changing the basic model in three ways. First I have aligned the model to reflect the concept that the main constituent assets of law firms are elements of Intellectual Capital, rather than tangible assets. Second, I have developed the Balanced Scorecard methodology to fit the environment in which lawyers develop their careers by serving their clients, processing their work, and making profits. Third, I have restated the Scorecard in terms which fit in with both the background and strategic imperatives of most law firms.

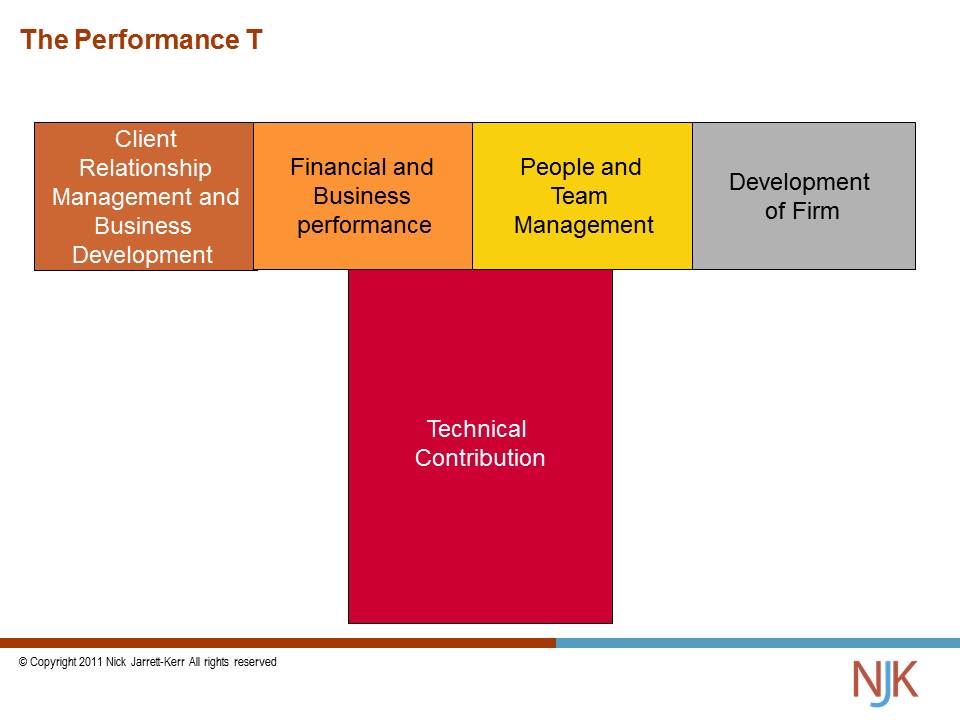

Some firms like to express their balanced scorecard or Critical Areas of Performance in the form of a T. The vertical part of the T illustrates the depth of the lawyer’s technical expertise. The horizontal bar shows the breadth of the professional’s overall contribution as a manager and an owner. The newly promoted partner, for instance, should show a strong and deep technical expertise but may not have developed broader management expertise; his or her T will be more in the shape of an ‘I’ or a hammerhead. As the partner develops, the horizontal bar will extend until it reaches a balanced proportion. It is also quite possible – perhaps in the case of a managing partner – for the management skills on the horizontal bar to predominate to the virtual exclusion of the vertical ‘technical skills’ part of the bar. Hence, the difficult task facing former managing partners and senior partners is to re-build their technical skills or to face leaving the firm.

- 2. Defining Roles and Responsibilities

The creation of a Balanced Scorecard is not however the end of the story. The Balanced Scorecard helps to define the skills, competencies and contributions in general which the firm needs to develop within the firm. It is however also vital to define the various roles and responsibilities within firms which partners may have from the senior partner downwards. In this context, a strategy mapping process will help the firm to identify the areas where partners should have a role in assisting the firm towards its goals and objectives. The strategy map shown here is based upon the four perspectives of the Balanced Scorecard but is further divided into twelve areas all of which any firm needs to decide on the lines of responsibility and accountability. Whilst all partners have an interest in all twelve areas, some may have particular responsibilities which need to be clarified. In this paper, there is only space to consider by way of example the two levels at the bottom of the map.

2.1. Human Capital

The development of skills and capabilities within the firm is one area where all partners have a responsibility. The question of alignment and mix – how many lawyers are needed, the ratios of support staff to lawyers and non-partners to partners – and recruitment are all more strategic questions and may be (depending on the size and type of the firm) the responsibility of the firm’s managing partner, human resources partner, practice groups heads and professional management staff.

2.2. Structural Capital

In considering the firm as an institution, its competitive positioning is a strategic matter to which all partners may contribute but for which the managing partner may bear the primary responsibility. The development of the firm’s business model may be a board matter or may be a matter for practice group heads to work through in connection with their specific practice areas. The monitoring and support of the positive traits in a firm’s culture should be supported and contributed to by all partners but – again – the managing partner may have an overriding responsibilities. The development of the firm’s disciplines, structures, decision-making and profit-sharing are all matters on which partners need to agree but which the firm’s leaders need to drive through.

What then should happen is that the firm works out and agrees the divisions and definitions of the various roles and responsibilities within the firm.

2.3. Typical Roles of Senior Partner and Managing Partner

2.3.1. Senior Partner

Purpose and Objectives

- To develop the Firm’s Profile and its reputation in its chosen markets

- To facilitate effective inter-Partner relationships

- To lead and support the Managing Partner or Chief Executive in the management of the Firm

Responsibilities:

- To chair as necessary all meetings of the Partners and to develop the effectiveness of those meetings

- To represent the Firm in the external market-place as ambassador, spokesman and figure-head

- To manage inter-Partner relationships, and to counsel, advise, coach and mentor Partners

- To act as the link and moderating influence between the Board and the Partners, so as to achieve or enable

- (for the Board) the ability to move the business forward without interference from Partners and Partnership Politics

- (for the Partners) the right degree of influence and consensus in the management and leadership of the Firm

- To assist the Board, and the Managing Partner and the Executive Management Team in the development and implementation of the firms strategy

- To take part in the Firm’s Partner Appraisal program

2.3.2. Managing Partner

Whether the role is full-time or part-time, the individual who is responsible for leading the firm as Managing Partner needs some clarity about his or her job description and the authority delegated to him or her.

Purpose and Objectives of Managing Partner

- To be responsible for the economic performance of the firm

- To lead the Partnership in establishing a clear vision and strategy for the Firm

- To establish and maintain forward-looking, efficient and effective management of the Firm

Powers and responsibilities:

To fulfil his/her responsibility to the Partnership for the effective management of the Firm, the Managing Partner often has a range of executive powers to enable him/her to lead, manage and remain in overall control of the firm on an operational basis and to deliver the Objectives of the Firm. Some Firms prefer not to define these responsibilities too closely but they can often include the following responsibilities

- To manage and remain in overall control of the management of the Firm (and each office) within it on an operational basis

- To ensure that the Partners and Fee Earners are effective in the delivery of the Firm’s services to its clients and do so profitably

- To lead the Management Team in developing, for approval by the Partners at appropriate times, the Firm’s business and operational plan, including budgets, so as to achieve maximum profitability

- To have the power, subject where appropriate to agreement by the Board to authorise all budgeted expenditure, and to have some authority over unbudgeted expenditure

- To ensure that the Firm’s Budget and Business Plan are implemented and that progress is monitored regularly throughout the year

- To implement the agreed Partner disciplines of the Practice and to monitor and police all Partner Accountabilities

- To take such executive decisions, in conjunction with the Board, as may appear from time to time necessary in order to secure the smooth running, management, profitability and leadership of the profit centre

- To co-ordinate and control the Firm’s drawing policy, including changes in the drawing policy

- To be responsible for the appointment, removal and performance assessment of the Department Heads and Management Team