How Partner Compensation Can Support Strategic Goals and Economic Objectives

For many firms, partner compensation has long been managed in isolation from their overall business strategy, which is primarily focused on external factors, such as markets and clients. But, by aligning compensation models with strategic objectives, firms will be far better equipped to achieve their goals.

For many firms, partner compensation has long been managed in isolation from their overall business strategy, which is primarily focused on external factors, such as markets and clients. But, by aligning compensation models with strategic objectives, firms will be far better equipped to achieve their goals.

The Kerma Partners’ ‘Global Survey of Large Law Firm Compensation Practices’, which we examine in this issue, draws some interesting conclusions about the latest trends in compensation practices and highlights amongst other things the effect of national cultural differences in the way compensation is handled across the world. Although culture plays a part, there is no doubt that the shifts that are taking place also reflect a continuing quest by firms to establish ways in which partners behaviours and individual performances link with the firm’s overall strategic goals and the achievement of the firm’s economic objectives.

The pursuit of a cohesive and coordinated strategy has not always been the norm in law firms. It has to be remembered that many law firms started as a loose collection of lawyers all pursuing their own individual goals. Some law firms are still run very successfully that way. In the United States, there are still some markedly successful firms operating on a highly individualistic business model. In the United Kingdom, for example, the long established model of the barrister’s chambers is an example of a collective enterprise where some essential costs and infrastructure requirements are met jointly, but in which individual barristers pursue their own independent businesses within that framework. In terms of rewards and profitsharing, the barrister’s chambers are the ultimate example of an eat-what-you-kill system, which continues to work well. For most law firms, however, the increasing demands of clients for strength in depth and a consistent offering across a range of well-managed specialised services mean a different business model and a collaborative strategy.

| Partner independence is being gradually eroded in favour of corporate disciplines. |

In medium size and smaller firms, the same restrictions on partner autonomy are not so evident. Even so, such firms often operate on a body of the unwritten rules that partners learn by working at the firm — the signals, attitudes and working ways that are seen to be valued and expected. Time and time again, it is clear that whilst partners are slow to adopt new skills and behaviours, they usually do not take long to realise the behaviours that are in reality expected and actually valued at their firm. In the face of increasing competitive pressures, firms continue to build strategies that are dependent on the firm moving upstream and competing for better clients, great specialisation and higher value work. It is therefore critically important to be clear about what the firm expects of its partners, and what roles and responsibilities it needs them to perform in pursuit of such strategies.

Most law firms do nothing like enough to review their strategies on a regular, frequent and consistent basis. Indeed, if you ask the average partner of even quite a large firm what he thinks the firm’s strategic plan is, the answers you will get are often muddled, differ between partners of the same firm, and at times are limited to the individual partner’s sense of where his own career is heading. Even if you get a clear answer from partners about the firm’s strategy, many partners are very muddled or confused as to where they fit into it or are planning to contribute to it. What is more, there is typically confusion between strategy and various other elements — such as marketing, systems, and structure — which may form part of the strategy, but are not in fact strategy themselves.

As many of our articles and writings have frequently asserted1, strategic thinking should be externally focused on markets and clients, and not internally focused on questions of technology, rewards, morale, training and similar issues. As has sometimes been said, strategy is concerned with making and baking the cake, and profit allocation and distribution is about cutting the cake. However, there does have to be an alignment between the externally facing strategy of the firm and the reality of the internal structures, systems and culture. It is dangerous to think about strategy in total isolation from the resources, skills and ability of the firm needed to implement strategic goals.

I have found, however, that when firms think about partner progression, compensation and rewards, it is somewhat unusual for the firm at the same time to revisit or even to make the necessary links with their strategic planning and what they are trying to achieve as a firm. The focus is solely on cake-cutting rather than cakemaking. What’s worrying is that things are moving so fast that firms ought to be reviewing their strategies more often than in the past, not less often. And that statement presupposes that the firms in question know roughly their purpose and destiny. This is a bigger assumption than may be thought; most firms answer quite strongly that they know exactly where they are going and how they are going to get there, but the evidence often points to the contrary.

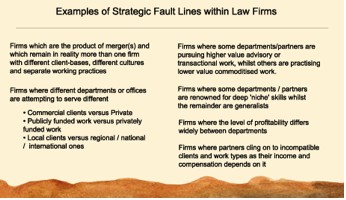

I have been constantly surprised by the number of even quite large law firms where the leading partners (or in some cases whole practice areas and departments) are each following their own quite separate strategies in relation to their own practice areas without a unified plan holding the whole enterprise together. It may be that a sort of working accommodation has emerged over the years with historically few problems. But like a yacht with no single guiding hand on the tiller, it is, in those cases, entirely a matter of luck and tradition as to whether the firm’s overall direction and purpose is both consistent and competitive. Indeed many such firms have severe fault lines, which are either ignored or suppressed. The fact is that most firms remain, at least in part, a semi-detached collection of individuals and practice areas that have been formed over time on an unplanned and opportunistic basis. As the quality and size of the client base grows, the need increases for more than one partner to work for clients and engagements. Partners therefore have to become used to working together, sometimes in situations which, given an entirely clean sheet of paper, they would never contemplate.

As firms grow, the chances of conflicts also arise and it is vital for firms and partners to understand the circumstances when conflicting clients or work types must be abandoned. It is easier to make such difficult decisions in a firm where sharing is more common than in more individualistic practices. There are, for example, still some law firms around that have traditionally acted for both claimants and defendant insurers in personal injury cases. In other firms, such a possibility would not for a moment be contemplated, either because the insurance clients would oppose such a practice, or for internal reasons such as the clash in culture and working practices. For the same reason, it is rare to find in law firms’ employment and labour law practice groups a dual focus on advising both employers and employees. It is usually one or the other. But some firms persist in trying to be all things to all men. “We have always done it that way”, is one justification. Another and perhaps more fundamental issue is that it is difficult to persuade individual partners to give up clients or conflicting areas of law, particularly if this significantly prejudices their income stream in a formulaic or eat-what-you-kill system.

The problem is that fault lines can exist, sometimes for many years, without too apparent a problem. But underneath, fault-line firms have two strategic disabilities. First, and invariably, the existence of the fault-line commands internal attention and energy on an ongoing basis — energy and time that will accordingly not be available for moving the firm forwards. Second, and more difficult to prove, any firm with substantial internal issues will fail to achieve its long-term potential even in its strongest areas. In short, I believe the firm will underperform in all its chosen markets. This may sound like a strong claim, but I challenge you to name me a law firm with an underlying fault-line, which has done better than it would have done with a focused and consistent strategy. Like a yacht with more than one hand on the tiller, which can never be sailed tightly and efficiently, such a firm is hampered by its tradition and history.

Sadly, many firms choose to ignore such faultlines and limp on through the problems. The more honest and ultimately more sensible route is to address such fault-lines sooner rather than later even if this means dumping a practice area.

Four Ways In Which A Partner Remuneration And Compensation Scheme Can Support The Firm’s Strategy

There are four main ways in which a Compensation and Rewards System can support the firm’s strategic direction and goals.

First, the system can help to underpin a unified understanding of where the firm wants to go, where it is likely to prove to be successful and what trade-offs are likely to take place along the way. Sadly, many compensation systems reward the past, and perhaps the immediate and shortterm future; those who are working prospectively towards longer term goals can lose out in the piesharing contest. I spoke to one partner recently at a sophisticated global law firm who is devoting all his time to creating a new service offering and capability focused on an emerging market. He was resigned in the short term to suffering penalties in his compensation but was convinced that in the long term his firm would start to recognise and reward his effort and his vision for what could be an exciting new offering. It is somewhat sad that in his case the investment seems to be a personal and individual one rather than being shared across the firm.

Additionally, many firms are what one might describe as portfolio firms with a host of different practice areas, specialisations and client types. In such firms, there is often a vying for both position and resources between competing partners and practice areas whose drive and commitment is directed more towards their own part of the firm than towards the firm as a whole. Recruitment strategy is a good example. Here, firm leaders should pause to work out where their firm’s best effort and their limited resources should be applied rather than reacting to bids for resources and new recruits from power partners who view their own discipline as being the most important. An honest confrontation of what Jim Collins has referred to as “the brutal facts of current reality”2 is a good start. Collins’ study of good-to-great firms illustrated that firms need to found their strategies on a deep understanding along three key dimensions — what the firm can be best at, what drives the firm’s economic engine and what activities ignite the partners’ passions. This somewhat simplistic view of strategy nevertheless helps to make the point that firms need a shared vision about what is likely to drive success in the future. This shared vision should ultimately cascade down from corporate strategic goals to individual objectives. This is not easy. Partners value their own independence highly and have come to regard their own performance and practice area as the vital determinant in their personal progression and rewards formula. In place of this, some firms are starting to ask partners to become focused on the firm’s corporate success more than the results of any individual partner’s efforts. As August Aquila and Coral Rice3 put it, “Too often, under the old model, owners focused only on their own enrichment and betterment. As long as they won, they did not care if anyone lost. The goals of each owner were independent rather than interdependent. The focus of the new compensation model has changed. Firms are moving toward interdependent goals that develop a culture of cooperation, teamwork and abundance”.

Second, the compensation and profit-sharing system can support the firm’s strategy and the overall value of the firm’s offering by esteeming and rewarding those who create value. For many law firms, this concept involves a complete change in thinking both on the part of the leadership of the law firm and its partners. Historically, law firms have concentrated on this year’s profits and performance sometimes to the exclusion of longterm investment. Since the time, roughly half a century ago, when goodwill ceased to be written into law firm’s accounts, partners in law firms have had little or no incentive to think of their firm other than as a provider of income during their practising lives. The concept of the firm as a valuable capital asset has until recently been far from the minds of most lawyers.

The advent in the UK of the Legal Services Act 2007 and similar deregulatory action elsewhere in the world has already led to firms taking on outside investment, changing ownership for a capital consideration and even floating on stock markets. These events and changes are beyond the scope of this article, but have the welcome side effect of starting to encourage firms to consider their intangible assets and intellectual capital. It is important to recognise that part of any law firm’s strategy must be to have a plan for building long-term value across all facets of its intellectual capital.4 In this connection, the aim must be to consider future income streams as well as present ones. Hence, partners should be encouraged to devote at least some of their efforts to areas that will not necessarily result in a huge level of revenue in the immediate future. This will involve partners building long-term client and network relationships, and spending precious non-billable time developing their team, their specialisations and their skills. It also involves the investment of energy in streamlining processes, building efficient working practices and cost effective service-delivery mechanisms. These activities, however, should not be sporadic efforts of individualism but rather should be part of a concerted collaborative effort aimed at value creation as well as financial performance. A recent survey5 has shown that the top drivers of employee engagement and retention are an understanding of strategic direction and leadership, communication and client focus.

| Employees who are highly engaged, committed and focused…are two and a half times more likely to be top performers |

Employees who are highly engaged, committed and focused — with a clear line of sight to their organisation’s business goals — are two and a half times more likely to be top performers than their less engaged peers.

Third, the system can encourage lawyers to work towards some distinguishing features, which enable the firm to stand out from the crowd. Much of a lawyer’s day to day activities consist of doing the much the same work for much the same body of clients as last week or last year. As mentioned earlier, however, firms cannot prosper with a strategy that relies primarily on continuing to do as the firm has always done. A ‘do-nothing’ strategy will inevitably result in a gradual erosion of both margin and competitive position.

The fourth and final link with strategy is the connection with the firm’s overall objectives. A well-thought-through compensation and profit-sharing system can help a firm to achieve its growth objectives whether those objectives entail a growth in size or in substance and depth of skills (or both). The important challenge is to align the compensations system to fit the firm’s goals. Firms that are heavily in growth mode will often be attracted to a compensation system that will allow them to scale up quickly by making individual partners economically accountable in the short term for the expansion of their unit or office. A compensation system that focuses and rewards specifically for individual partner performance can act to transfer, at least in part, some of the expansion risk of a firm in a growth cycle. In contrast, the pursuit of bigger clients and more complex work may require a compensation system that is based on more of a sharing model. Furthermore, a more collaborative compensation system aligns well with firms for which the building of deep skills or an emphasis on teamwork is strategically important. It can however be easier in an eat-what-you-kill firm to make a business case for the firm to invest in a new laterally hired partner than, say, in a lockstep firm where the firm will be required to subsidise the whole cost centrally.

1 – See for instance, Ed Wesemann “Driving Strategy — the three keys Leaders must know“, and “Creating Dominance“, “Grass Roots Strategy” by Nick Jarrett-Kerr and “How Do You Practice Strategy” by Friedrich Blase – www.KermaPartners.com

2 – Jim Collins, Good to Great, 2001, Random House.

3 – August J Aquila and Coral L Rice, Compensation as a Strategic Asset, 2007, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

4 – Nick Jarrett-Kerr and Friedrich Blase , “How Valuable are Your Assets” (2007) by available on www.KermaPartners.com

5 – Watson Wyatt, Bridging the Employee Engagement Gap, 2007.

(all available at www.KermaPartners.com)

Managing Expectations: Compensating Unique Lateral Partners by Ed Wesemann

Linking Partner Targets To Profit Shares by Nick Jarrett-Kerr

Ten Terrible Truths About Law Firm Partner Compensation by Ed Wesemann